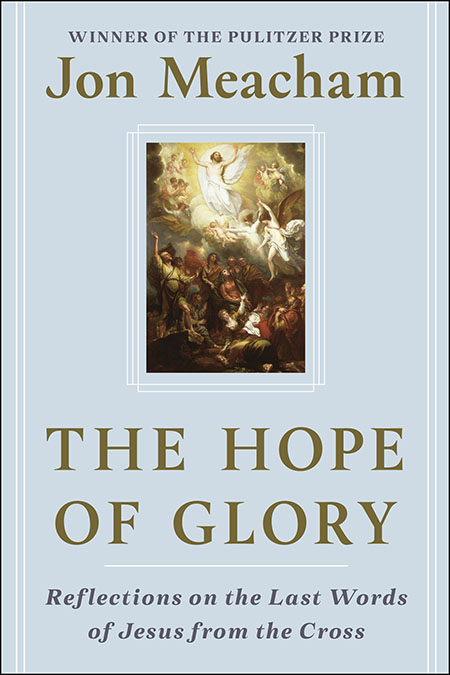

Crime, Culture, and Complicity

Beverly Lowry’s Deer Creek Drive weaves true crime with memoir

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This article originally appeared on August 18, 2022.

***

Beverly Lowry’s 10th book weaves true crime with a memoir of the post-WWII South. Focused on the brutal killing of a Mississippi socialite, Deer Creek Drive: A Reckoning of Memory and Murder in the Mississippi Delta revisits an event that grabbed national headlines, left lingering questions, and is still met with silence in the Delta town of Leland.

In 1948, a Mississippi “social matron” named Idella Thompson was stabbed at least 150 times with a pair of garden shears. Doctors and authorities arrived at Thompson’s home on tony Deer Creek Drive, where the victim had been found by her adult daughter, Ruth Dickins. Despite strong evidence that Ruth was the killer, she blamed the event on an unfamiliar Black man. Given this commonplace, cruel accusation — and when the consequent shakedown of the Black community petered out — the exception to the usual process was Ruth’s being tried for murder. The event was a media sensation, as was Ruth’s conviction and incarceration.

Deer Creek Drive is in many ways an investigation of justice as impacted by culture and community. The book spares no detail about the murder, the trial, or the pedigrees at stake, while also examining the larger role and legacy of Jim Crow. The resultant researched nonfiction can still read like a thriller. The writing blends archival history with casual observation, empathy, even wit.

Layered into the crime story is Lowry’s memoir of growing up in nearby Greenville, including her recollection of the trial. The distance between the author’s semi-stable upbringing and that of heritage-class Deer Creek Drive adds dimension to white Mississippi, a space some still refer to as more country club than state. Lowry describes how mid-century Delta society was the stuff of Virginia private college and debutante balls and the gentility of a “planter” (never “farmer”) social caste. We learn how these details influenced the crime scene, turning authorities away from the facts right in front of them.

Lowry is meticulous in pursuit of conflicting leads and secondary suspects, and she revisits questions that shadowed Thompson family history and business. She guides the reader into the blank space of motive and nagging doubt, then puts us square in the courthouse, segregated and sweltering, where Ruth Dickins is found guilty. Bringing home the spectacle of the trial, Lowry cites the New York Daily News, which proclaimed that “Dickins may follow Lizzie Borden into macabre immortality.”

Lowry is meticulous in pursuit of conflicting leads and secondary suspects, and she revisits questions that shadowed Thompson family history and business. She guides the reader into the blank space of motive and nagging doubt, then puts us square in the courthouse, segregated and sweltering, where Ruth Dickins is found guilty. Bringing home the spectacle of the trial, Lowry cites the New York Daily News, which proclaimed that “Dickins may follow Lizzie Borden into macabre immortality.”

Ruth’s time at Parchman prison is of particular importance. The notorious penal farm has featured in the fiction of Faulkner and Welty, in Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, and in the music of Muddy Waters, Leadbelly, and others. Freedom Riders were detained there, and it is an ever-active trauma site, most often to its Black population. (Parchman facilities were temporarily shuttered as recently as 2021, following a series of inmate deaths and a national media exposé.) In this context, Lowry presents an under-told narrative, pitting the state’s iron fist facility against the reach of establishment wealth. Ruth’s correspondence with the governor and her extended home release are contrasted with the experience of Parchman’s lesser-crime convicts, subjected at times to a bullwhip named “Black Annie.” Appeals for her release trended away from claims of innocence — shaky ground, at best — and to class-based terror. Ruth was, according to one, “‘a woman gently reared … in the closest association with prostitutes, thieves, and murderers, the vilest of womankind.’”

Though the memoir can feel separate from the Thompson murder, it adds complexity to the case and the era. Lowry reminds us that while Ruth Dickins’ family made personal appeals to the governor, Mamie Till’s Mississippi family bore witness to her son Emmett’s lynched body and saw his killers walk free. We gain insight from Lowry’s experience as a white high-schooler in the Brown v. Board storm, now a world-class writer who still can’t get Delta folks to open up. In a sense, her off-radar biography illustrates the insidious, day-to-day discrimination, as is the case when she transcribes the fine print on a Sugar Bowl ticket, “issued for a person of the Caucasian race, and if used by any other is in violation of state law.” Her attention to place and surnames will hit home for some Mississippians, as will the ongoing code of silence.

Poring over the evidence, leads, and dead-ends of Ruth’s trial emphasizes to Lowry that while her own life was removed from Deer Creek Drive, she was nonetheless raised on the receiving end of privilege. In reassessing this truth through the lens of a sensational crime, her book asks readers to consider — and confront — the larger role of culture and complicity.

Odie Lindsey is the author of the story collection We Come to Our Senses and the novel Some Go Home, both from W.W. Norton. He is writer-in-residence at the Center for Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University.