David and Goliath in Reverse

In The Snail Darter and the Dam, Zygmunt J.B. Plater recalls his landmark case against TVA

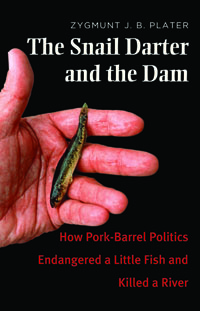

There was a time, not too long ago, when you could tell a lot about a Tennessean by his thoughts on the snail darter. The three-inch-long fish, a member of the perch family, lives in certain reaches of Chickamauga Creek and the Sequatchie River, both in East Tennessee. It used to live in the Little Tennessee River, too, until the Tennessee Valley Authority built the Tellico Dam, which destroyed the steady stream of fresh water that the fish needed to survive.

For some Tennesseans, it was a dam too far, a pork-barrel project that needlessly flooded thousands of acres of farmland and animal habitats. Deploying a raft of new environmental laws, activists used the snail darter’s status as an endangered species to delay the dam for almost a decade. But they could hold out only so long in the face of TVA’s gargantuan political power, and the dam was completed in 1979 after the authority’s allies in Congress forced through an exemption to the Endangered Species Act. The snail-darter case is a David and Goliath story in reverse, one in which the giant smothers the young king with an army of expensive lobbyists.

For some Tennesseans, it was a dam too far, a pork-barrel project that needlessly flooded thousands of acres of farmland and animal habitats. Deploying a raft of new environmental laws, activists used the snail darter’s status as an endangered species to delay the dam for almost a decade. But they could hold out only so long in the face of TVA’s gargantuan political power, and the dam was completed in 1979 after the authority’s allies in Congress forced through an exemption to the Endangered Species Act. The snail-darter case is a David and Goliath story in reverse, one in which the giant smothers the young king with an army of expensive lobbyists.

That, at least, is how the activists saw it. In fact, as documented by Zygmunt J.B. Plater, the University of Tennessee law professor who led the snail-darter case and the author of The Snail Darter and the Dam, most Tennesseans supported TVA and Tellico. More to the point, they were outraged at the thought of a tiny fish and its eco-warrior allies standing in the way of the state’s economic development. For them, the bad guy run amok was not TVA, but the environmental movement.

Plans for the dam went back to the early 1960s, when TVA first proposed to stopper the Little Tennessee at a point about thirty miles southwest of Knoxville. The dam would generate some power, but not much; the real goal was economic. A “model city” would rise on the shore of the new lake, along with a Boeing aerospace plant that would anchor millions of square feet of industrial space. TVA began to condemn some sixty square miles of farmland around the Little Tennessee, a substantial amount of which would never be flooded but was needed to ensure an attractive site for Boeing and other companies looking to settle in the area. The Tellico Dam, in other words, was a real-estate deal.

This all sounds a far cry from TVA’s founding mandate to generate power and produce fertilizer for the Tennessee Valley. Yes, it had performed the heroic deed of bringing electrical power to the impoverished Tennessee Valley (though, contrary to popular assumption, only about ten percent of its power supply in 1970 came from hydroelectric plants). Once that goal was achieved, though, it couldn’t settle with simply maintaining its existing infrastructure. Like any bureaucracy, it had to keep growing, using “development” as its justification for putting up dams long after the state stopped needing them. “It’s male menopause,” one candid TVA staffer told Plater. The men leading the TVA “came down here thirty years ago and saw themselves as saviors lifting this region up from nothing. They desperately want to lead the pack again.”

This all sounds a far cry from TVA’s founding mandate to generate power and produce fertilizer for the Tennessee Valley. Yes, it had performed the heroic deed of bringing electrical power to the impoverished Tennessee Valley (though, contrary to popular assumption, only about ten percent of its power supply in 1970 came from hydroelectric plants). Once that goal was achieved, though, it couldn’t settle with simply maintaining its existing infrastructure. Like any bureaucracy, it had to keep growing, using “development” as its justification for putting up dams long after the state stopped needing them. “It’s male menopause,” one candid TVA staffer told Plater. The men leading the TVA “came down here thirty years ago and saw themselves as saviors lifting this region up from nothing. They desperately want to lead the pack again.”

Opposition to the dam by local farmers grew through the late 1960s, though it achieved little; once a TVA project was begun, it was very hard to get it to stop, not only politically, but legally. Most statutes allowed broad exemptions for projects underway: agencies could weigh the environmental consequences of a project against its potential to generate economic growth—and also against the losses an agency would incur if it had to stop construction once a project was underway. In other words, the further along a project got, the harder it was to stop it. And it was almost impossible to halt the agency’s power of eminent domain, which it used to condemn thousands of square miles of private property over its lifetime, some of it in the name of specious “economic development” projects like the Tellico Dam.

Then, in 1974, Plater and a group of lawyers, law students, and local farmers hit on the newly passed Endangered Species Act—and the serendipitous discovery of the endangered snail darter in the Little Tennessee—as a way out. As Plater read the law, this time there was no possibility for exemption: if a project threatened an endangered species, it had to be stopped, no matter how big the project or how little the species.

Plater, who now teaches at Boston College, does a deft job of weaving together the legal framework and context for his fight against TVA, which he ended up winning before the Supreme Court in the landmark case TVA v. Hill. He employs a strict first-person, present-tense perspective that gives the book an engaging, memoiristic tone. Plater provides a wealth of detail that makes for compelling reading, and he has a knack for bringing drama to even the most technical court proceedings.

Unfortunately for the snail darter, Plater’s case appeared a few years too late. The time for path-breaking environmental activism was the mid-to-late -1960s; by the early-1970s, even as Congress continued to pass laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (which created the Environmental Protection Agency), large parts of the public had turned against activist government, and in particular against laws linked to left-wing social movements like environmentalism. In the eyes of many, the snail-darter case was government activism at its worst: the Endangered Species Act was meant to protect noble animals like elk and bald eagles, not tiny, inedible fish. The only reason the act was in play at all, they reasoned, was that Plater, a Yale-educated lawyer, had come in to stir up trouble.

Spurred on by a nascent conservative media machine, thousands of Tennesseans turned out in protest after the Supreme Court upheld the Endangered Species Act against the dam. Riding a wave of popular indignation, TVA and its allies in Congress, most notably Senator Howard Baker, drove through legislation to exempt the dam from endangered species laws. In the meantime, UT denied tenure to Plater because, he was told, law professors at UT needed to exhibit more “moderation” in off-hour legal pursuits. He took a job at Wayne State University in Detroit and commuted, first to Tennessee and then to Washington. But all his efforts weren’t enough to block the dam.

The tragedy is that while Plater and his colleagues, in their efforts to block the dam by any means necessary, felt they had little choice but to pursue the endangered-species strategy, that strategy doomed them in the public’s eyes as tree-hugging “humaniacs” who cared more about the well-being of a fish than the economic prospects of their fellow Tennesseans. They might have opposed the project on a property-rights basis: even if TVA had expansive powers of eminent domain, the dam’s opponents might still have succeeded in swaying public opinion against this massive overreach by the government. One wonders, even, whether the legacy of environmental laws might be less tainted among conservative Americans if the first test case of the Endangered Species Act hadn’t been a tiny fish.

TVA long maintained that the snail darter could be successfully transplanted to other rivers nearby and so wasn’t endangered in the first place. And so far, it seems, they were right: relocated darter populations are thriving in the Chickamauga and elsewhere. Plater, say his opponents, was simply wrong.

None of which diminishes the rightness of his cause. Plater ends his book with a series of photos, three of which are particularly telling. One shows a McMansion on the shores the Tellico Reservoir, built on land that had been taken from small-hold farm families by the TVA. The other two show the tops of grain silos poking up from the middle of the reservoir, the haunting remnants of the many farms that once dotted the now inundated land. This, not the life or death of the snail darter, is the real legacy of the Tellico Dam project.