Death Is the Mother of Beauty

Poet Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum talks with Chapter 16 about grief, memory, and healing

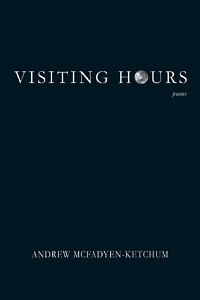

Poet Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum’s Visiting Hours is a stunning elegy for Mary Interlandi, who in 2003 drove to the top of the Sheraton hotel parking garage in Nashville and leapt to her death. She was 19 years old and a lifelong friend of the poet, and their connection permeates the collection with a gripping vulnerability. It is at once sweeping and focused, grand and intimate.

Visiting Hours is ultimately an invitation to join McFadyen-Ketchum in communing with and grieving for Mary’s spirit, and his writing dances with immersive, lyrical detail. Dualities abound in these poems; they grapple with relationship and loneliness, beauty and pain, grief’s paralysis, and love’s creativity. Utilizing couplets to emphasize these dichotomies, as well other forms, McFadyen-Ketchum creates a poignant, graceful collection. He investigates the social, political, and personal facets of grief and explores the possibility of finding meaning in the aftermath of tragedy.

In an email exchange, McFadyen-Ketchum shared his thoughts about the process of writing Visiting Hours, the night sky, influences on his work, and more.

Chapter 16: When you began writing these poems, was it your intention to include them in an elegiac collection dedicated to Mary?

Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum: It was. Her suicide was such a devastating landmark in my life that when she died in 2003 I immediately started writing about her, which is why my first book, Ghost Gear, includes a poem about Mary. I was in the second year of my M.F.A. at Southern Illinois University Carbondale in 2007 when I began Visiting Hours. It felt natural and right to me to dedicate a collection to her. In my grief, I knew I needed to write a book about her to heal myself and to share that healing — to create a way to share her light and to share how devastating it is to lose a dear one to suicide.

I took it upon myself that winter to write “Marysarias,” which was at one point the title poem for the book, and which the book hinges upon. I was stunned when I took it into workshop that spring and this massive, ten-page poem that largely takes place in the dream/psychic realm was well received. I had accomplished something in that poem I wasn’t sure I could, and that workshop affirmed to me that I could write the sort of book I wanted to about Mary — an account of grief and healing, a book of dreams and what ifs, a book that embodied a loss that was otherwise inexpressible.

The rest followed from there. For 10 years, I worked on this book, writing and discarding poems and feverishly revising the ones that, for whatever reason, declared they belonged in the collection, in between adjuncting, starting an editing business, publishing and promoting Ghost Gear, and surviving divorce.

It wasn’t until 2017 that I knew I had Mary’s book and started submitting it. Just like with “Marysarias,” Visiting Hours immediately resonated with its audience, and I knew that eventually it would make its way into the world. Now, finally, it is here. It has been an incredible 13-year journey. To finally have her in my hands again brings me great joy and, if I’m being honest, some sadness too. The first copy I received in the mail came on the 17th anniversary of her death.

Chapter 16: In one section of the title poem, you explore guilt and shame as a form that grief can take: “blame anything / but me.” The narrator’s grief is palpable. How did grief inform your process of writing this book?

Chapter 16: In one section of the title poem, you explore guilt and shame as a form that grief can take: “blame anything / but me.” The narrator’s grief is palpable. How did grief inform your process of writing this book?

McFadyen-Ketchum: I was an undergrad at Virginia Tech when my sister called at 3 a.m. to inform me of what Mary had done. I dropped the phone (it put a tiny little dent in the hardwood floor) and wailed. This scene recurs throughout the book because I knew Mary was going to take her own life. I was well aware of her depression, and, in many ways, the girl I’d known all my life was already gone at that point.

It’s hard to describe. I’ve tried to describe it in the book: She just wasn’t herself anymore. We’d talk on the phone, and I’d wonder if this was Mary I was really talking to. I was already horribly afraid she was going to take her own life when that 3 a.m. phone call came, but I was hopeful that some sort of treatment would save her, that she would decide to live for those who loved her, that … something would intervene and keep her with us.

But she did kill herself, and while there was nothing anyone could have done to stop her, I felt horribly guilty until, well, I finished the book. Visiting Hours was the only way for me to abate my grief enough to forgive myself (and to forgive everyone else who was unable to save her life) and to come to terms with the virulent lie of depression: that we are irreparably disconnected and of no significance … that we are somehow a burden to our loved ones … that we have no value….

Mary taught me more about life and the importance of living it, in spite of pain and loss, in spite of the lie of depression, than any other experience. Our lives are simply too important to those we leave behind. I saw the anguish her vanishing caused her family, my family, the Nashville community, and me. I don’t think Mary knew what she was doing. If she had, she wouldn’t have jumped off that building. I wrote Visiting Hours for many reasons; one reason was to help those considering suicide to understand the horror that is losing you. It doesn’t matter what you have done or how you feel: Stay. Just stay.

Chapter 16: Throughout the collection, you utilize couplets. The duality of that form seems to mirror dualities in the content (grief/love, beauty/pain). How did the subject matter come to bear on your form choices?

McFadyen-Ketchum: One of the primary conflicts of the book is between me and Mary and within myself. Many times, Mary expresses a desire to sleep, to be left alone, to be at peace, yet the speaker, who is consumed by writing this entire book about her, forces her into the light, refuses to let her be. Visiting Hours is an attempt to refuse her death, to resurrect her in the only way I can — through verse that was the result of deep meditation, prayer, grief, and love. The couplets express, structurally, the enormous tension of this duality — this internal and external conflict for both subject (Mary) and poet (me).

I have been in conflict with myself for 17 years about losing Mary and about this book: You let your childhood friend kill herself and now you’re refusing to let this poor, tired girl stay dead? Who do you think you are? I asked myself this many times. Throughout the process, I shared these poems with her family. They always gave me their blessing. I can’t imagine what it is like for them to now have this book in their hands, but they have never wavered. They always permitted me to write about their daughter. So I did my best to honor their trust.

The conflict between Mary and me was resolved in the writing of Visiting Hours. The conflict with myself dissipates by publishing it, by sharing these verses about my friend, the one I could not save, in a book-length elegy. In this book, I have attempted to build a space for her in the realm of the living; now, it is readers who hold that space for her. It is readers who actually manifest that space by reading about Mary. It is the community who saves her in ways we could not while she was alive.

Chapter 16: The moon and stars are recurrent images in these poems. In “Marysarias,” Mary is conceived from constellations. “Smith Lake” ends with the devastating lines “Mary backlit by darkness, Mary slipping / into the moon.” Can you talk a little bit about the role of night sky imagery in these poems? Does it have a particular meaning for you?

McFadyen-Ketchum: I am obsessed with the heavens. I took the photograph of the moon on the cover and on the section pages. Whenever I look at the moon, even if just for a moment, I think of Mary. She is always there in that natural satellite. It’s nothing new to look to the stars and remember the dead. I’m just borrowing from the ancients. The writing of poetry is an act of borrowing from those who came before us. The act of living is an act of borrowing from our forbearers. Thus the ever-present moon and stars in Visiting Hours. Thus the cover: a dark night lit by a full moon.

Chapter 16: The sharp contrast between lyric descriptions of nature and the buzzing everyday life of downtown Nashville is a constant juxtaposition, particularly in “Marysarias,” as Mary leaps from the Sheraton parking garage while everyday people go about their mundane tasks. How important was it for you to articulate the particularities of Nashville as the context for these poems?

McFadyen-Ketchum: Very. When Mary took her life, the entire city suffered. Nashville is practically a character in the book. When she took her life, she destroyed a part of my home. I live five minutes from the Sheraton. Every day while driving to daycare with my toddler, I see the Sheraton on the skyline: There is her devastating final act. Mary destroyed my sense of Nashville when she destroyed herself.

That idea was one of the most important ideas I wanted to express in Visiting Hours. When you kill yourself, the lives of those you leave behind are changed forever — as is the place you come from, the places you frequent, the lives of those you have never met. Only once have I driven to the top of that rooftop to see where Mary took her life. It was a very difficult experience. I imagine I’ll go up there sometime soon with the book and offer it to her. She’s still up there. She always will be.

Chapter 16: There’s a Whitmanesque quality to your work in its ability to sharply outline details, as well as speak to large, sweeping themes. Whose work has influenced yours, particularly this book? How did James Kimbrell inspire the title?

McFadyen-Ketchum: Many of the poems are modeled after other poems. The first poem owes a huge debt of gratitude to Sylvia Plath’s “Poppies in October,” although her influence is one of many that poetry enthusiasts will recognize through this collection. As for Kimbrell, I modeled “Visiting Hours” off of his amazing poem (and title poem of his first collection), “The Gatehouse Heaven.” The Gatehouse Heaven examines his father’s insanity and the conflicted relationship between father and son. It didn’t influence the title, but he certainly showed me that I could write a book about a single person. The other major influence on the book is Judy Jordan’s Carolina Ghost Woods, which elegizes her mother who died when she was a child. Without those two books, I don’t know that I could have written Visiting Hours.

I titled the book Visiting Hours because, in my grief, each poem felt like an opportunity to visit with Mary, and I hope the reader feels the same way.

I have more influences than I can count, and over the last 13 years they have been celebrated at PoemoftheWeek.com. If I’ve featured a poet there, they have inspired me and Visiting Hours. It’s almost a little embarrassing the number of poets who have made me, but that is something most poets share: we all stand on the shoulders of giants.

Chapter 16: In the penultimate poem, “On the One Hundredth Anniversary of Mary’s Death,” the narrator declares: “I will say your name no more.” In the final poem, “Epistle,” the statement is made true as Mary’s name becomes “M— .” What was the impetus for finishing the book in this way?

McFadyen-Ketchum: I say Mary’s name all the time, but I don’t write about her anymore. The journey from conception of this book to its birth was a long, painful, and healing one. The moment I finished Visiting Hours by writing that final line, an expression of gratitude to Mary and her death, “Thank you, my love, for saving my life,” I knew it was time to move on poetically, and I have. Now I am writing about surviving my divorce and finding true love and family in the aftermath of it. I am writing happy poems about my children, none of whom are genetically mine, and all three of whom bring me a joy I have dreamed of my entire life. Mary’s death was the first tragedy I lived through that taught me the all-important lesson of gratitude. Mary’s death taught me to live, no matter the suffering, to be grateful for what I have no matter what darkness.

“Death,” a famous poet wrote, “is the mother of beauty.” Visiting Hours was born the moment Mary leapt from that building. I pray it is beautiful. My god, please please please, let it be beautiful.

[Read an excerpt from Visiting Hours here.]

Lauren Turner is a multidisciplinary artist in Nashville. Her writing has appeared in The East Nashvillian, Women’s Review of Books, and Image Journal’s “Good Letters“ blog. She also serves as a blog editor for Nashville’s community radio station, WXNA FM, where she hosts her program The Crack in Everything.