Descent into Freedom

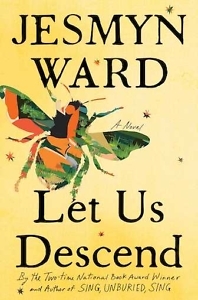

Jesmyn Ward’s Let Us Descend is a chronicle of survival and liberation

Following her National Book Award-winning 2017 novel, Sing Unburied, Sing, Jesmyn Ward returns with Let Us Descend, the story of an enslaved young woman, Annis, who is sold south by the white enslaver who raped her mother.

Annis is not only a young woman — she is also a warrior. Or at the very least, she has been trained as such from childhood by her mother during clandestine practice fights in the antebellum night. It is this instilled warrior mentality that will carry Annis through her descent into darkness.

The novel’s title alludes to Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, the first part of his 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. Inferno follows Dante on his necessary journey through the concentric circles of hell, toward a spiritual enlightenment. Ward draws an important parallel early in the novel, when Annis overhears instruction on the plantation:

The tutor is telling a story of a man, an ancient Italian, who is walking down into hell. The hell he travels has levels like my father’s house. The tutor says: “‘Let us descend,’ the poet now began, ‘and enter this blind world,’” and his words echo through me. I hear the sighs: the summer wind pushing slant at the house, the wood groaning, but instead of the Italian poet descending into hell, I see my mother toiling in the hell of this house.

Annis first identifies her mother as a type of Dante. But as the novel progresses, we find that Annis herself is also a version of Dante, following various tutors (older, wiser enslaved people) into the deepening circles of hell. “I wonder if the Italian man felt like this on his downward walk, wonder if his mind snagged on all in the upper world that ever bought him ease and pleasure.” She is forced to walk along with her intimate friend, Safi, and several other chained men and roped women to New Orleans. The road is red-earthed. It is not merely hellish. It is hell.

The language throughout the book is otherworldy, which befits Ward’s genre-combining style. It is at once period piece and fantasy. “The world is thick with spirit, Mama said, and if you call it, you should gift it: trinkets of shells and cloth made only for their beauty, nose-pinching herbs and ripe fruit. I got nothing but my split feet, my skin growing to the rope, and my blood in the sand. I got nothing but myself.”

The language throughout the book is otherworldy, which befits Ward’s genre-combining style. It is at once period piece and fantasy. “The world is thick with spirit, Mama said, and if you call it, you should gift it: trinkets of shells and cloth made only for their beauty, nose-pinching herbs and ripe fruit. I got nothing but my split feet, my skin growing to the rope, and my blood in the sand. I got nothing but myself.”

Words like ‘sere’ and ‘nursemaid,’ which Annis uses to describe her enslaved mother, bring the reader back to this dim period in American history. The narrator refers to her enslaver as her sire, which seems to subvert the usual indignities that go along with the word master. If he is her sire and not her master, she recognizes a relationship of power but is not defined by it.

It is interesting to note that the wind, the trees, the rivers are all characters in this novel, evoking a type of animism historically associated with African cultures. It adds a layer of richness to the tone of the work. Ward writes: “I would sweep you along to the ocean and islands yonder, the river murmurs. The wood rips from my hands, takes skin with it, draws blood. More offering. The river laughs.” These natural characters experience a type of freedom that seems to reveal possibilities to Annis. The rivers, the trees can commit acts or serve as conduits to liberation.

The novel is flavored by a hunger for freedom, not merely the freedom from enslavement but freedom toward the kind of self-determination that recognizes one’s own desires. Annis reflects, “I want. I want to grow my hair long, to find food and feed myself without hiding, to sit in the sunlight and scratch the worry out my scalp, to breathe without fear and terror choking me, to choose my seconds, to choose my minutes, to choose my days. I done suffered enough.”

Let Us Descend is about grief and belonging, but it is not merely about belonging to community and home; it is about belonging to oneself. As the protagonist realizes at last, “They [the enslavers] will want what they believe is theirs.” The most empowering course of action then, is to take oneself back, to believe, as Annis does, in the voices of the rivers, the trees, the wind, and the ancestors, all guides through hell.

[Read Chapter 16’s 2011 interview with Jesmyn Ward here.]

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian who received the 2023 Humanities Tennessee Fellowship in Criticism. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters and is at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.