Diverse and Complicated

Three Appalachian women tell their stories in Voices Worth the Listening

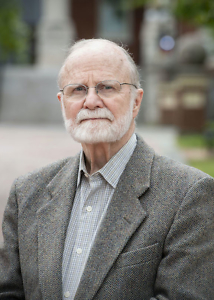

In the introduction to Thomas Burton’s Voices Worth the Listening: Three Women of Appalachia, the author recalls a remark once made by a new colleague at East Tennessee State University, where Burton is professor emeritus of English: “You’ve been out among these people in Appalachia — what makes them ‘tick’?” the colleague asked.

Burton was taken aback. “Well, there are wood ticks and there are clocks that tick,” he quipped, using wry humor to divert the conversation from the assumption that “the essence of Appalachia and its people as a whole can be absolutely perceived and succinctly delineated.” As he explains in this slim volume of ethnographic interviews with three women from the Blue Ridge Mountains, Appalachians are too “diverse and complicated” for that.

To Burton, whose previous work includes documentaries and a book on Pentecostal snake handlers, a better approach is found in Act III, Scene 2 of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in which the Danish prince remarks, “Why, look you now, how unworthy a thing you make of me! … you would pluck out the heart of my mystery.”

Presenting the women’s lives in their own words, Burton invites readers to consider their mystery by following “each of the women as though you were having the opportunity and the privilege … to watch a player present her own private role ‘as ’twere the mirror up to nature.’”

All born between 1961 and 1971, the women speak of early desires, relationships, money, and trouble. Two are white and one is Black. None are named, but each woman’s story is preceded by a “portrait” (education, work, life situation), “personae” (parents, husbands, friends, children), and “themes” (religion, alcoholism, legal struggles, successes).

The first woman, white and born in 1971, is homeless — though “things didn’t start this way.” Raised by her mother and grandparents, she remembers happy times helping her grandmother can fruit. But she didn’t have a father (“My mother messed around with a married man and ended up with me”), and happy times were marred by alcoholism. Pregnant at 15, she married her boyfriend, who beat her. “When you are in an abusive relationship, some people think you can just walk out of it. … It’s just not that simple.” Finally leaving, she earned a GED and found work managing a burrito stand but lost her children and attempted suicide. As the interview ends, she is unsure what will happen. “I hope it’ll all work out. We’ll see.”

The first woman, white and born in 1971, is homeless — though “things didn’t start this way.” Raised by her mother and grandparents, she remembers happy times helping her grandmother can fruit. But she didn’t have a father (“My mother messed around with a married man and ended up with me”), and happy times were marred by alcoholism. Pregnant at 15, she married her boyfriend, who beat her. “When you are in an abusive relationship, some people think you can just walk out of it. … It’s just not that simple.” Finally leaving, she earned a GED and found work managing a burrito stand but lost her children and attempted suicide. As the interview ends, she is unsure what will happen. “I hope it’ll all work out. We’ll see.”

The second woman, also white, was born in 1968 to “strict Southern Baptist Republicans.” Her father was an army officer. “We ate, drank, breathed everything ‘America’ … and we went to church every time the doors were open.” A rebellious teenager, she skipped school and smoked pot. She started college but met a guy at “a rough bar on the edge of town.” One day, he told her he was going to AutoZone. “He told me he’d be right back. But he didn’t come back.” Calling hospitals and police, she learned he had been murdered in a drug deal. “After that I stayed angry a long, long time — angry, angry.” She worked and took antidepressants but spent time in jail and lost custody of her daughters after marrying a man who cooked meth. As her story ends, she knows she must “get out of this hole.”

The oldest woman, born in 1961, is Black. Growing up in public housing, she started work at 14. Despite good grades in high school, she was not encouraged to pursue a career. Pregnant and unmarried, she applied for welfare. “I did the welfare thing because most people I knew were on welfare,” she says. Then a woman who hired her to do odd jobs encouraged her to attend college. She earned a nursing degree, working in health care while raising her children. Although her husband was on crack and spent time in jail, he had a religious conversion. In the end, she looks forward to a happy retirement. “Whatever environment a person’s in, they have to make choices,” she says.

In the foreword to Voices Worth the Listening, Erika Brady of Western Kentucky University compares the book to Studs Terkel’s 1974 classic, Working. The comparison seems apt, yet Burton’s book is edgier. Unshaped by a literary story arc and unsullied by analysis, the stories feel raw, and it is difficult to say who the intended audience is. Certainly, the book speaks volumes about women’s struggle with agency and resilience. However, because Burton implicitly asks readers to take the stories as they are, it feels wrong to look for such patterns.

Maybe that’s the point — to listen without judging or categorizing. Taken as such, these stories allow readers to hear voices of women often silenced, providing a window into human experience that might otherwise pass into history unrecorded.

Jane Marcellus’ essays have appeared in journals including The Gettysburg Review, Syracuse Review, and Hippocampus. Her work was listed as “Notable” in The Best American Essays for 2018 and 2019. She is a professor at Middle Tennessee State University.