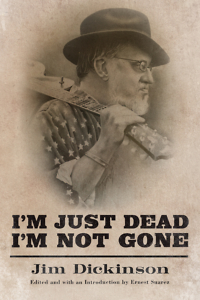

Dixie Fried

Jim Dickinson’s memoir is a powerful journey through Memphis music

In his memoir, I’m Just Dead, I’m Not Gone, Jim Dickinson recalls one of his early projects as a record producer with the famed Memphis-based Ardent studios. In 1967, Dickinson produced the first album by a struggling Arkansas rock combo that would become 1970s Southern Rock superstars Black Oak Arkansas.

“[They were] the most original group I ever recorded,” Dickinson writes, “like nothing I’ve heard. They had seen photos of Jefferson Airplane but never heard their music, so they played how they imagined it sounded.” Originality notwithstanding, studios were in no rush to record the group, as Dickinson points out: “Homer Ray Harris had thrown them out of Lyn-Lou’s studio for playing too loud. Chips [Moman] wouldn’t let them in American. I couldn’t wait.”

“[They were] the most original group I ever recorded,” Dickinson writes, “like nothing I’ve heard. They had seen photos of Jefferson Airplane but never heard their music, so they played how they imagined it sounded.” Originality notwithstanding, studios were in no rush to record the group, as Dickinson points out: “Homer Ray Harris had thrown them out of Lyn-Lou’s studio for playing too loud. Chips [Moman] wouldn’t let them in American. I couldn’t wait.”

That embrace of the unconventional and a love for musical eccentrics was a guiding principle throughout Dickinson’s life and career. As a musician, songwriter, record producer, and raconteur, Dickinson was a singular figure in the Memphis music scene from the time of his first high-school rock’n’roll bands in the late 1950s through his death in 2009. During his career, he worked with an amazing lineup of musicians ranging from superstars like Aretha Franklin, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan to beloved “cult” artists like Big Star, Tav Falco’s Panther Burns, and the Replacements.

Born in Little Rock, Arkansas, Dickinson spent his early childhood in Chicago. He was seven when his family moved to Memphis in the summer of 1949. Although Memphis was racially segregated, both legally and geographically, Dickinson entered his teenage years in a city where the walls that separated black and white music and culture were rapidly crumbling. Dickinson captures the atmosphere of that heady era in an atypical narrative that flips between prose and poetry. Consider this sketch of the city on the cusp of the rock’n’roll revolution:

Memphis was strange and wonderful in the 1950s, with colorful local heroes like stock-car outlaw Hooker Hood, Sputnik Monroe “The World’s Greatest Wrestler,” and Daddy-o Dewey, who blasted the airwaves with “Red Hot and Blue.” Elvis represented a lifestyle that already existed in Memphis.

Hoods

Rogues

Teenage rebels

Greasers with sculptured baroque pompadoured dragon tail hair cuts

Pegged

Draped

Pimp pink zoot suits

Direct from Beale Street

Silk on silk

Lace front tux shirts

With collars turned up

Were an open invitation

To rumbleTwo cultures, divided for centuries by race and property rights, reached for each other musically, and inevitably embraced and collided.

Interspaced with impressionistic poetical observations are straightforward passages recreating touchstone moments from Dickinson’s life. His discovery of the blues through a radio performance by legendary bluesman Howlin’ Wolf, Dickinson’s checkered college career and love for theatrical pursuits, his personal quest to locate the grave of bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson—all these reminiscences crackle with passion and vividness. In both moments of personal transcendence and celebrity-spiced anecdotes, Dickinson writes with a sharp eye for detail, an appreciation of absurdity, and an awareness of the deeper insights to be found in seemingly mundane moments. When he was recruited to play piano on the 1969 Rolling Stones session that produced the hit single “Wild Horses,” Dickinson writes,

Interspaced with impressionistic poetical observations are straightforward passages recreating touchstone moments from Dickinson’s life. His discovery of the blues through a radio performance by legendary bluesman Howlin’ Wolf, Dickinson’s checkered college career and love for theatrical pursuits, his personal quest to locate the grave of bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson—all these reminiscences crackle with passion and vividness. In both moments of personal transcendence and celebrity-spiced anecdotes, Dickinson writes with a sharp eye for detail, an appreciation of absurdity, and an awareness of the deeper insights to be found in seemingly mundane moments. When he was recruited to play piano on the 1969 Rolling Stones session that produced the hit single “Wild Horses,” Dickinson writes,

[The Stones] were too out of tune for the studio’s concert grand and the Wurlitzer. I sought the old upright tack piano in the back of the studio where they had their cocaine stashed… I found a section of the old piano just out of tune enough to work with the Stones, and started trying to interpret the chord chart I had gotten from Keith. It was instantly apparent something was wrong.

Bill Wyman saw me having trouble, and said, “Where’d ya get them chords, mate?”

“I got them from Keith.”

“Pay no attention to him,” he said. “He has no idea what he’s doing. He only knows where he put his fingers yesterday.” This is the best description of rock’n’roll guitar playing I have heard.

Written over several years, the manuscript for I’m Just Dead, I’m Not Gone, was unfinished when Dickinson passed away following heart surgery. His widow, Mary Lindsay Dickinson, and his oldest son, Luther Dickinson, transcribed the text from the original handwritten manuscript.

As an unfinished work, I’m Just Dead, I’m Not Gone covers Dickinson’s life only through 1972, but Dickinson had already written the perfect ending for his book: an account of his appearance at the 2004 Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival as a member of the “Hill Country Revue,” a Memphis music supergroup that included Dickinson; his sons’ band, the North Mississippi Allstars; blues patriarch R.L. Burnside and his sons; and Othar Turner’s fife and drum band. As with the rest of his memoir, Dickinson looks beyond mere recollections, ending his story with a rumination on the power of music to unite children of the Confederacy with the children of slaves and past generations with those yet to come.

Randy Fox is a freelance writer whose writing on music and pop culture has appeared in Vintage Rock, Record Collector, The East Nashvillian, Nashville Scene, Jack Kirby Collector, Hardboiled, and many other publications. He lives in Nashville.