Dream Images

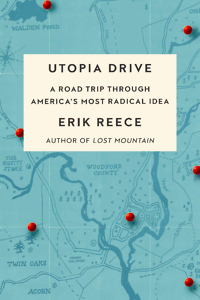

Erik Reece takes a road trip through America’s experiments in utopian living

Utopia Drive: A Road Trip Through America’s Most Radical Idea is an account of Erik Reece’s journey to some of America’s utopian communities, past and present. Reece is the ideal author for a book on this subject because he embodies the openness, kindness, and meditative consciousness needed to consider seriously these communal alternatives to the American way. And he lives enough of an alternative life himself to capture the allure, never romanticized, of those living even more radically in opposition to the “great political, economic, social, and environmental crises” of our time.

In a way, Reece is a young, transcendental Wendell Berry. Like Berry, he’s a lifelong Kentuckian who makes his home close to the embrace of the land; like Berry, he teaches and writes as a form of prayer; and like Berry he practices what he preaches. But instead of using Berry’s Christian language of salvation, resurrection, and grace, Reece leans toward the vocabulary of Thoreau and Emerson: truth, beauty, justice, and peace. He recently answered questions about Utopia Drive via email:

In a way, Reece is a young, transcendental Wendell Berry. Like Berry, he’s a lifelong Kentuckian who makes his home close to the embrace of the land; like Berry, he teaches and writes as a form of prayer; and like Berry he practices what he preaches. But instead of using Berry’s Christian language of salvation, resurrection, and grace, Reece leans toward the vocabulary of Thoreau and Emerson: truth, beauty, justice, and peace. He recently answered questions about Utopia Drive via email:

Chapter 16: George B. Lockwood’s The New Harmony Movement, a book you picked up in 1986, triggered your fascination with American utopian communities, but it wasn’t until last October that you “finally felt ready” to embark on a road trip to visit some of these communities. Why now?

Reece: The main reason is that I had become so despondent about the state of the nation—income disparities, unsustainable resource consumption, a political system that had been hijacked by the financial system—that I felt this psychological pull toward these communities that represented such a radical alternative. I wanted to salvage those stories and hold them up as still latent forms of real inspiration for how we might move forward. The German theorist Walter Benjamin called such ruins “dream images,” and he believed they could be recontextualized to image a better future. So, in a way, I was driving through the past and looking for those portentous dream images.

Chapter 16: You visit the Shakers at Pleasant Hill early in your journey, and you mention that your mentor, Guy Davenport, hung a Shaker broom in his writing studio, a suggestion “that art or artisanship, whether it be Shaker broom or Shaker dance, is the form we give to forces that we feel and struggle to articulate.” What are these forces to you, and what form do you give them?

Reece: I harbor a deep fear about the future of this country, both as a functioning democracy and as an environmentally sustainable place to live. Like my fellow Kentuckian Wendell Berry, much of my writing is motivated by that fear. But I’m also motivated by the possibility that we might bring more beauty and conviviality into our daily and communal lives. So I suppose the form those forces have taken are the books I’ve written: Lost Mountain, American Gospel, and Utopia Drive. I might also add the form of my marriage, my garden, and the wooden boat I built a few years back.

Chapter 16: You highlight the idea of “realized eschatology,” the transformation of life and relationships with others in the present time instead of focusing on the future. What prevents most of us from embodying this change?

Reece: Wow, you need a book to answer that question! I think as a nation we have made Christianity too future-focused because that’s easier than actually implementing, say, the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount. As I mention in the book, the Shakers and the Perfectionists took literally and seriously the injunction in the Book of Acts that said Christian communities should hold all property in common. That’s straight-up socialism, right? But you will never hear it preached in a mainline Christian church. It’s too inconvenient, and we Americans seem to want a very convenient belief system. We want, as G.B. Shaw said in another context, “a nice light religion for the summer.”

Chapter 16: Alexander Bryan Johnson, a philosopher, “argued that words are blunt and inadequate instruments for representing reality,” as you note. “Whereas nature always shows itself in an infinite display of particularity, words always rise to the level of the general, so that a rose is a rose is a rose.” How do you reconcile a project of words, like your own, with the limitations of language that Johnson illuminates?

Chapter 16: Alexander Bryan Johnson, a philosopher, “argued that words are blunt and inadequate instruments for representing reality,” as you note. “Whereas nature always shows itself in an infinite display of particularity, words always rise to the level of the general, so that a rose is a rose is a rose.” How do you reconcile a project of words, like your own, with the limitations of language that Johnson illuminates?

Reece: One way is that I always do prioritize the natural world as the original scripture, what Walt Whitman called a “realm of budding bibles.” There is great nature poetry, like Wendell’s, that can help us see that world better and hopefully make us better stewards of that world. But the world is always the primary text. I also think it’s important for anyone using words to acknowledge they are in many ways blunt instruments, but they are all we have, and they are often very beautiful.

Chapter 16: You eventually arrive at perhaps the most well-known utopian project in American history—Thoreau’s Walden Pond: “Every [person] is tasked to make his life, even in its details, worthy of contemplation of his most elevated and critical hour,” Thoreau writes. “The poet’s experience becomes the poem.” How do we begin this journey ourselves?

Reece: I think by taking Gary Snyder’s advice to find a place and dig in. Take responsibility for that place and for your actions there. This doesn’t have to be a rural place; it can be a place in the city. In fact, for most of us, it should be that. But that also means making our cities more inspiring, less homogenous, and more worthy of contemplation.

Win Bassett’s work has appeared in publications including The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Oxford American, The Paris Review Daily, and Guernica. He serves as Editor-at-Large for The Sewanee Review and lives in Nashville.