Dreams and Nightmares

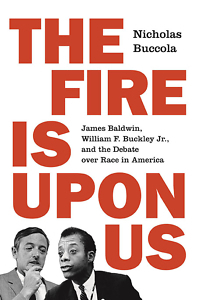

Nicholas Buccola dissects the dramatic 1965 debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley

On February 18, 1965, in the hallowed halls of the Cambridge Union in England, James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. debated a resolution: “The American dream is at the expense of the American Negro.” As Nicholas Buccola describes in his fascinating history, The Fire is Upon Us, these two leading public intellectuals cast differing visions of race in the United States — visions rooted in their personal histories, political ideals, and moral constitutions.

Nicholas Buccola is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield University in McMinnville, Oregon. The Fire is Upon Us was a 2019 New York Times Editors’ Choice. Buccola’s previous books include The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass: In Pursuit of American Liberty. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Nicholas Buccola is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield University in McMinnville, Oregon. The Fire is Upon Us was a 2019 New York Times Editors’ Choice. Buccola’s previous books include The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass: In Pursuit of American Liberty. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: What brings both James Baldwin and William Buckley to Cambridge in 1965? Why do they agree to the debate, and what do they hope to accomplish?

Nicholas Buccola: This was one of the first mysteries I set out to solve when I began research for the book. Next to nothing had been written about the backstory of the debate. Fortunately, many of the students who planned and hosted the debate are still living, so I was able to interview them. The debate came to be as the result of a book tour Baldwin was on to promote the paperback release of Another Country, his third novel. His publicist sought to book an event at the Cambridge Union, and the Union president said they would be happy to host him if he would be willing to debate (since the Union was, after all, a debating society). Buckley’s invitation to square off against Baldwin was the result of another Cambridge student, who happened to meet Buckley in 1963 and knew enough about him to know he would be the perfect antagonist for Baldwin.

I think Buckley and Baldwin had different motivations for agreeing to debate. Buckley was always eager to engage in intellectual combat with ideological adversaries. That was kind of his thing. His goal in the encounter was to warn the international audience that Baldwin was a dangerous radical, hell-bent on overthrowing Western civilization.

Baldwin had less to gain from the encounter. Indeed, his agent tried to cancel the debate just days before the clash. Although Baldwin could display radical empathy for his political opponents, he thought Buckley and his ilk deserved radical confrontation. From Baldwin’s point of view, Buckley was most interested in conserving one thing: his own power. Baldwin felt obliged to reveal that to the world.

Chapter 16: Baldwin is once again a subject of critical and popular attention. How does his work speak to us, as Americans, in this current political moment?

Buccola: Baldwin’s enduring relevance is, in my view, due to the intellectual radicalism of his project. By that, I mean “radical” in its original sense: Baldwin sought to get to the root of things. In his fiction, non-fiction, and activism, Baldwin was attempting to solve the puzzle that lies at the nexus of identity, morality, and power. Through his fictional characters and nonfiction subjects, Baldwin explored who human beings take themselves to be and how those conceptions of identity lead them to treat other people. If we want to make sense of racial politics, sexual politics, or any other kind of politics, Baldwin insisted that we must try to understand why we construct our sense of self in ways that make us feel superior to others.

Baldwin’s great insight is that our identity crises as individuals are at the core of our moral and political troubles. If we would stop lying to ourselves about who we really are and about the nature of life, the world might become a more just place. This insight is always urgent and relevant, but I think it has gained greater attention in the broader culture because more people are recognizing the reality of the American racial nightmare.

Chapter 16: What was Buckley’s interpretation of the civil rights movement? How does he shape the relationship between modern conservatism and race?

Buccola: Buckley viewed the civil rights movement with suspicion at almost every turn. He conceded that African Americans were often treated unjustly and thought some forms of social protest were legitimate, such as economic boycotts. But he was critical of Black liberation, again and again. Buckley’s circle at the National Review was against the Brown v. Board decision, critical of the sit-in protesters, critical of the freedom riders, supportive of jury nullification of federal civil rights laws, against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and against the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In 1957, Buckley infamously argued “the white community” was entitled to rule because it was, for the time being, “the advanced race.”

As time passed and he lost many battles in the civil rights struggle, Buckley avoided explicitly white supremacist language and endorsed what we might call a “colorblind” response to Black liberation. Buckley also celebrated “white backlash” politics in the mid-to-late 1960s as a necessary corrective to the “excesses” of the civil rights movement.

Baldwin’s lens helped me make sense of what Buckley and his crew were up to. Racist politics have become slightly more subtle over the years, he would tell us, but no less deadly.

Chapter 16: You write that, in Baldwin’s remarks at Cambridge, he attacked “the mythology of the American dream.” How so?

Chapter 16: You write that, in Baldwin’s remarks at Cambridge, he attacked “the mythology of the American dream.” How so?

Buccola: One of Baldwin’s central goals was to liberate us from mythology, which we rely upon to avoid coming to terms with our personal and collective histories. This evasion undermines our ability to achieve fulfillment as individuals, and it prevents us from moving our society toward justice. As a mythology, the American dream has its uses, but it becomes dangerous — from Baldwin’s point of view — when it allows us to avoid truths about ourselves.

One aspect of the mythology of the American dream is the idea that, if you work hard and play by the rules, you can achieve success. In his speech, Baldwin reminded the audience of just how hard his ancestors worked and that they did this “for nothing; for nothing.” This is not merely a historical point. History, he reminds us, is present in everything we do. That legacy of exploitation is all around us, if only we have the courage to see it.

Chapter 16: As he responded to Baldwin, did Buckley define an “American dream”? How did he see the past, and how did he envision the future?

Buccola: Buckley did not address the motion as clearly as one would like, but the working definition of the American dream he used in the speech is the idea of “the mobile society.” He tended to emphasize the material opportunities available in the United States. Buckley’s basic rhetorical strategy was to concede that African Americans have often been denied participation in the American dream in the past and that there is still some injustice in the present, but “we” are making progress; “we” offer greater mobility than any other society; and “we” must be careful to avoid correcting our shortcomings in ways that might undermine the American dream for everybody.

In the speech at Cambridge, Buckley emphasized that racial injustice is the result of immoral individuals, not unjust institutions. He cautioned to go slow and not to abandon the “faith of our fathers” in the process. One of the slogans of the civil rights movement was “Freedom Now!” I say in the book that Buckley’s slogan for the civil rights movement would be: “Some freedom, one day, when we decide you are ready.”

Chapter 16: “The story of Baldwin and Buckley,” you write, “reminds us that moral righteousness is often not sufficient to gain political power. This is a sad truth, but it is a truth we ignore at our peril.” How is this idea reflected in the lives of Baldwin and Buckley in the aftermath of the Cambridge debate?

Buccola: One of the book’s central themes is that, although Baldwin is triumphant at the “battle” in Cambridge, there is a sense in which he loses the “war” with Buckley for the American soul. That statement is a bit too grand, of course, because the “American soul” is never just one thing. But my point is that we have not achieved the country that Baldwin hoped we might achieve.

There are many reasons to say we have achieved or maintained the country Buckley wanted. Conservatives dominate all three branches of government, and inequality has only deepened in the half-century since Baldwin and Buckley squared off. Baldwin was always more comfortable speaking in a moral vocabulary than he was speaking in a purely political one. At the Cambridge debate, he has this haunting line. He says that what concerns him most is that we will become so unwilling to listen to each other that the very authority of reason will break down.

And look where we are now. In such a world, how far can moral appeals carry us? If they cannot carry us far enough, then what? It seems to me as we watch the fabric of the republic unravel, these questions ought to be at the forefront of our minds.

Aram Goudsouzian is a professor in the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.