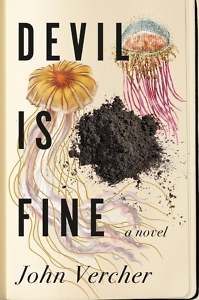

Duality Is Fine

John Vercher’s latest novel reckons with Black identity in the past and present

Devil is Fine is John Vercher’s third novel on biraciality. In this book, he takes us to a coastal town and to grief. Both locales, we discover, are sites of absurdism. A biracial father grieves his deceased son and dying career, realizing that he only understands both through a post-mortem examination. To further complicate matters, he finds himself the sudden owner of a former plantation, whose haunting blurs the line between reality and imagination.

John Vercher’s work has appeared in Booklist, Lit Hub, Entropy Magazine, and other literary outlets. He serves on the faculty of Randolph College’s low-residency M.F.A. program and is currently artist-in-residence in the Department of English at Monmouth University. Ahead of his appearance at the 2024 Southern Festival of Books, Vercher talked with Chapter 16 about his latest book and his writing process. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: Like your previous novels After the Lights Go Out and Three-Fifths, your latest project, Devil Is Fine, deals with themes of biraciality. Why was it important for you to continue exploring the intersections of biracial identity in this novel?

John Vercher: The best answer I have is that I am still exploring it in my own life. While fiction and writing should never be therapy, it can often be therapeutic. Readers are getting a front row seat to me working out my things, which is exploring these ideas of what it means to be mixed and to be Black in this country and to reckon with the history of white supremacy and colonialism as relates to my physical presence on the Earth. Those are things that I didn’t really have the world or life experience to explore in my 20s or even think to interrogate, and now that I’m in my late 40s I’m exploring that more and more. And so I think that as long as I continue to have questions, I’m going to continue to write about those types of themes.

Chapter 16: Do you think that it is only certain writers who have the obligation, like biracial writers, to write biracial protagonists?

Vercher: That’s a great question — and it’s so germane to what’s happening in publishing over the last decade or so. I have a hard time giving solid answers about that, not in the sense that I want to be political, but in the sense that it’s hard for me to say anybody can’t write anything. But at the same time, if you’re not coming from a place of authenticity or lived experience, I don’t see how you can speak to it in a way that’s going to resonate with the audience you might be seeking. So, I think that anybody can write anything, but they have to be prepared for the consequences of writing anything if they’re not coming from that lived experience.

Chapter 16: So, the audience will be able to test the verity of the writer’s intention or the truth of their experience?

Vercher: Yeah, I mean I hate to paint it with such a wide brush that all readers can do that, but I think the audience to whom you’re intending that message has a pretty good bullshit detector. So, I think in many cases that’s true.

Chapter 16: Audience is particularly important in this novel since it is addressed to the protagonist’s deceased son. Thinking of it in the style of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me and the first essay in James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, would you talk about the power of addressing Black boys in literature?

Vercher: I wish I could say I thought about it with that level of scope, but this was much more a personal exploration of the Black son of a Black father and trying not to repeat the mistakes of the past as a child who has now become a parent. I can’t say I was making this larger monolithic statement about speaking directly to Black children and Black sons in particular, but now that you say that, I kinda see where it fits in that conversation. But I have to be honest, it was much more personal for me. It was again about me exploring what it’s like to be a child-father. I feel like I’m still my father’s son, but I am also now a father to two boys I’m trying to responsibly raise and hope to avoid things that were challenging for me and my father.

Vercher: I wish I could say I thought about it with that level of scope, but this was much more a personal exploration of the Black son of a Black father and trying not to repeat the mistakes of the past as a child who has now become a parent. I can’t say I was making this larger monolithic statement about speaking directly to Black children and Black sons in particular, but now that you say that, I kinda see where it fits in that conversation. But I have to be honest, it was much more personal for me. It was again about me exploring what it’s like to be a child-father. I feel like I’m still my father’s son, but I am also now a father to two boys I’m trying to responsibly raise and hope to avoid things that were challenging for me and my father.

Chapter 16: What do you mean by that phrase “a child-father”?

Vercher: Because I feel like I’m still a kid, I still feel like I am the son trying to figure out how to be a dad, as opposed to having this thing figured out and I’m in this place of authority and know how I’m going to be able to hand-deliver every situation that arises from my own children. And I see myself as a big kid anyway. I still play video games with my kids. I still love comic books. I still love all those things that teenage me loved. It’s crazy how much leeway you’re given as a parent just because you’re a parent, like you’ve got this all figured out. And that’s not even close to the truth.

Chapter 16: Does continuing to identify as a child or identify with your childness keep you connected to source and trying to figure out who you are?

Vercher: Oh, without a doubt because so much of my childhood was spent in that identity limbo. When I was growing up, my hair was not like my dad’s. My dad sported a huge proud Afro and my hair was long and wavy. I was inundated with the “what are you anyway?” questions. You get that question asked of you often enough and you start to ask yourself that question. My dad was taking me on car trips at age 7 and telling me what it was going to be like to be biracial and Black in this country, so I knew I was Black. But when people started questioning me, I was like “Am I? Am I Black enough for this? Do I look…?” Those things kind of stick and they follow you all the way until you’re 48 years old. It’s been different now that I’ve lost my hair and shave my head and I’m now more visibly Black, but those identity questions still linger.

Chapter 16: Devil Is Fine also tackles the post-2020 equity rollbacks in both the publishing and academic worlds. As one of your characters confesses: “Maybe the university will respond by setting up a DEI committee. Maybe. Hell, they’ll probably have me lead it, that is until interest wanes, which we both know won’t take long.” Since you’ve had work released just before and, unfortunately, after the racial reckoning, how have you seen the mainstream demand for your work change? How do you keep motivated?

Vercher: It’s kind of you to think that there is any mainstream demand for my work because I don’t think I’m there yet. But I feel like I’ve been an observer to those for whom there has been mainstream demand, and that was the importance for me telling that part of the story in the book. It’s not like it was that long ago, but I remember with clarity, how, post the murder of George Floyd, in entertainment circles you couldn’t turn on a streamer without seeing Black stories. And all of these dedicated categories for our work and people were getting deals left and right for screenwriting and books. Even the publishing industry shifted from like 99.9% cis straight white men and females to 75/25, which is still terrible, but it was better than it has been. We watched that scale go right back in the other direction. All of a sudden HBO was pulling deals and shutting down divisions. And people who were hired to help with diversity, equity, and inclusion, whose departments were getting wiped out. So, while I was never in the center of that because I was not that mainstream, people in my orbit were and I felt a responsibility to call it out.

Chapter 16: The novel can be described as Kafkaesque, in the ways that you set magical realism in conversation with cultural criticism. Why did you choose the jellyfish as a vehicle to this end?

Vercher: It’s funny. So, it started off with a piece of autofiction that I wanted to include, simply because I knew I was setting this in a beach town. The bit of story where our narrator as a child goes out in the water and is surrounded by those jellyfish is a fairly true-to-life story. And part of me was like, “I’ve written myself into a corner here,” in the sense that it’s a great story to tell, but it’s gotta mean something. I ended up falling down this rabbit hole of researching jellyfish, and what became very apparent to me, and even after the book was published, is the duality of jellyfish. They have this ability — they’re so fragile, they can be torn apart so easily, and yet they can withstand thousands of pounds of pressure of water. They’ve been around for millennia. They’re beautiful to look at, but they’re deadly in some cases. And it got me to thinking about the comparisons — not just the idea that two things can be true at once, which is concept that we as human beings have a problem with, but there were parallels to the idea that, yes, you can have a white parent and a Black parent and still be Black. You can be a product of a biracial marriage and still interrogate some of the problematic nature linked to colonialism and white supremacy and still love that, but still question it. All of those things felt like they really lined up with this creature that has so much inherent duality.

Chapter 16: That’s powerful. Thinking about this scene in the novel, have you eaten jellyfish before?

Vercher: [Laughs] No. It’s something I kind of can’t bring myself to do. It’s like eating octopus in sushi. It’s like you know how intelligent they are, and I just can’t bring myself to do it.

Chapter 16: I feel the same and, it’s interesting, that emerges in the protagonist’s disgust with the idea of eating the jellyfish. I found that scene fascinating and I was repulsed. Ugh.

Vercher: You’re one of the first people to call out that scene, so thank you. I love that scene.

Chapter 16: What would people be surprised to know about your writing practice?

Vercher: How chaotic is. I don’t have a schedule. I don’t go for word counts every day. I am very much a sit and dwell and marinate on stuff until I actually sit down at the keyboard [writer]. But I am a firm believer in the idea that reading is writing. Thinking about writing is writing. It feels very gatekeeping and almost elitist to say that if you don’t do it every day, you’re not a writer. If you’re not physically putting words on the page. That feels like that’s meant to keep people away and it’s just never resonated with me. I don’t like to go through and do reams of revisions. I’d much rather sit down and put down what I feel is the best possible thing on the page so that my revisions process is much less strenuous. I’m not someone who waits for inspiration because I do believe if you wait for inspiration, it’s not going to come, but I do have to be moved to sit at the keyboard and put things down.

Chapter 16: Do you have any sacred texts that return you to the practice when you feel lost?

Vercher: There’s a few — I’m actually rereading one of them now, which is Paul Beatty’s The Sellout. There’s a weird duality in that book to me. It seems like a complete lack of restraint or care for what anybody thinks about what is on the page there, but yet you know beneath the surface that it’s very calculated. There’s something about that that is just masterful to me. This book was a departure from my earlier stuff in terms of being more experimental and surreal and absurdist. I can’t think of a better totem to go back to than his book. So that’s one. And then Matt Johnson’s Loving Day. When I want to find that balance between humor, but addressing themes in a serious way, that book makes me laugh out loud every time I read it, but then still also wrings me out in the best possible way.

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian who received the 2023 Humanities Tennessee Fellowship in Criticism. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters and is at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.