Each Day a New World

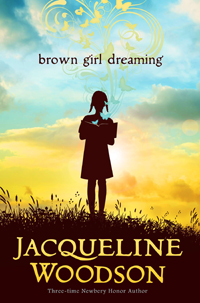

Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming is the story of a life told in soaring verse

In her memoir in verse, Brown Girl Dreaming—which has been longlisted for the 2014 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature—acclaimed children’s author Jacqueline Woodson writes about a life both unique and universal. Intertwining her own memories with stories told by friends and relatives, she is able to write about episodes that she was too young to remember herself but which were part of her family history and so helped to shape her character and outlook.

Woodson was born in Columbus, Ohio, and in one of the book’s early poems, her mother and maternal grandmother give vivid but different accounts of her birth, setting up the fluidity of memory as one of the central themes of the collection. Woodson’s parents had a turbulent marriage; her mother regularly took the children and returned to her own parents’ home in Greenville, South Carolina, finally settling there for an extended stay. Greenville, particularly the neighborhood of Nicholtown, becomes home to Jacqueline and her siblings. Neighbor children tease them for their Northern accent, but they soon settle into the close-knit community. On his way home from work, her grandfather calls out to the neighbors as he passes, Woodson writes, “His voice ringing down Hall Street, circling / round the roads of Nicholtown / and maybe out into the big, wide world….” There are murmurings of attacks on Freedom Riders, but in Brown Girl Dreaming we see the world through the eyes of a child, and, for her, the great love and security of her extended family are stronger than these threats.

Woodson was born in Columbus, Ohio, and in one of the book’s early poems, her mother and maternal grandmother give vivid but different accounts of her birth, setting up the fluidity of memory as one of the central themes of the collection. Woodson’s parents had a turbulent marriage; her mother regularly took the children and returned to her own parents’ home in Greenville, South Carolina, finally settling there for an extended stay. Greenville, particularly the neighborhood of Nicholtown, becomes home to Jacqueline and her siblings. Neighbor children tease them for their Northern accent, but they soon settle into the close-knit community. On his way home from work, her grandfather calls out to the neighbors as he passes, Woodson writes, “His voice ringing down Hall Street, circling / round the roads of Nicholtown / and maybe out into the big, wide world….” There are murmurings of attacks on Freedom Riders, but in Brown Girl Dreaming we see the world through the eyes of a child, and, for her, the great love and security of her extended family are stronger than these threats.

We see segregation, too, through the eyes of a child. For young Jacqueline, Jim Crow is an everyday part of life, and she leaves it to the words and actions of adults to reveal its crushing effects. Her grandmother won’t go into “the five-and-dime, which isn’t segregated now / but where a woman is paid, my grandmother says, / to follow colored people around in case they try to / steal something.” Instead, Jacqueline’s grandmother takes the children into the fabric store, where the white owner asks after the family and where “we are not Colored / or Negro. We are not thieves or shameful / or something to be hidden away. / At the fabric store, we’re just people.”

After several years in South Carolina, the family moves to Brooklyn. Far away from her grandparents, and especially missing the grandfather who had taken the place of her father, Woodson once again feels like an outsider: “This place is loud and strange / and nowhere I’m ever going to call / home.” A poem about a summer return trip to Greenville is entitled “Going Home Again,” but things have changed there too. Woodson’s grandfather has stopped working because of illness, and her grandmother has to work during the day. Greenville seems less like home now, and when they return to New York, Jacqueline says she is “home from Greenville.”

The point of view in these poems is always Woodson’s, and she is careful to convey events as they would be perceived by a child. So, for example, when the speaker in one poem describes the way her little brother peels and eats paint from the walls of their home in Brooklyn, she is unaware of the repurcussions of this behavior while many readers will understand that the paint probably contains lead and that the boy is in danger. An aunt dies in “a fall,” which must be the way the death was explained to six-year-old Woodson, but we’re left wondering: Suicide? Accident? Ultimately, the answer doesn’t matter; the importance of the death of her mother’s sister—so close that they’re mistaken for twins—is its emotional impact.

The point of view in these poems is always Woodson’s, and she is careful to convey events as they would be perceived by a child. So, for example, when the speaker in one poem describes the way her little brother peels and eats paint from the walls of their home in Brooklyn, she is unaware of the repurcussions of this behavior while many readers will understand that the paint probably contains lead and that the boy is in danger. An aunt dies in “a fall,” which must be the way the death was explained to six-year-old Woodson, but we’re left wondering: Suicide? Accident? Ultimately, the answer doesn’t matter; the importance of the death of her mother’s sister—so close that they’re mistaken for twins—is its emotional impact.

Brown Girl Dreaming traces young Woodson’s life chronologically, but each poem can also stand alone as a discrete work of art. Some poems are succinct, and others are more wandering. The language is at once delicate and powerful, lyrical and direct, sorrowful and humorous. Unlike many other so-called “novels in verse” or “memoirs in verse,” these are not just prose passages cut into lines of unequal length with some clever word play thrown in.

Ten of the short poems written as haiku are titled “How to Listen.” Woodson clearly is an expert at this art, not only listening but pondering overheard conversations—and, as she grows old enough, recording them in her journal. An ode to her black-and-white-speckled composition book shows the excitement of a young person discovering the power of writing.

Family ties are crucial to her story. In restrained, almost spare language, Woodson paints in-depth portraits of her grandparents, her mother, her siblings, and other family members. It’s fitting, then, that Brown Girl Dreaming opens with family trees of both sides of Woodson’s family and ends with family photographs taken during the time period depicted in the narrative. The final poem in Brown Girl Dreaming pays tribute to the influence of family and place, and to the power of the individual to forge her own identity. “Each day,” Woodson reminds us,

a new world

opens itself to you. And all the worlds you are—

Ohio and Greenville

Woodson and Irby

Gunnar’s child and Jack’s daughter

Jehovah’s Witness and nonbeliever

listener and writer

Jackie and Jacqueline

gather into one world

called You

where You decide

what each world

and each story

and each ending

will finally be.

This final poem—like Brown Girl Dreaming as a whole—is a triumphant celebration of an extraordinary, complex individual and the people and places who helped make her who she is.

Tracy Barrett is a writer who lives in Nashville. Her eleventh novel, a young-adult retelling of Snow White entitled Fair as Snow, will be published in June 2015 by Harlequin TEEN.