Eccentric Faith

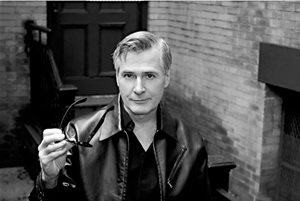

Award-winning playwright, screenwriter and director John Patrick Shanley talks with Chapter 16 about Doubt, faith, and theater

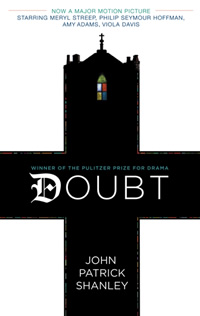

John Patrick Shanley’s 2005 play, Doubt: A Parable, won the Triple Crown for drama: a Tony Award, an Obie, and a Pulitzer Prize. The 2008 film version of Doubt, which Shanley directed, stars Meryl Streep and Phillip Seymour Hoffman and was nominated for Critic’s Choice Award, a Golden Globe, and an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. It wasn’t Shanley’s first run at the Oscar: his script, Moonstruck, won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay in 1988. His prolific output includes twenty-three plays and ten films—everything from the Emmy-nominated Live From Baghdad to Joe Versus the Volcano.

Born and raised in the Bronx, Shanley is a product of that borough’s parochial schools, a fact that figures heavily in the design of Doubt, the story of a mistrustful, conservative nun who suspects a progressive parish priest of having an inappropriate relationship with an altar boy.

Shanley spoke with Chapter 16 in advance of his talk at Lipscomb University’s thirtieth annual Christian Scholars’ Conference this week.

Chapter 16: Are you a practicing Catholic?

Chapter 16: Are you a practicing Catholic?

Shanley: No. But I had a lot of interaction with the Catholic Church during the making of Doubt, both the play and the movie. My first-grade schoolteacher was a Sister of Charity, Sister James. I put her in the play assuming she was dead, but it turned out she was very much alive. When I went to see one of the early previews of the play, I sat with her. She’s still a nun, and she’s still teaching. We had a powerful shared experience, so I hired her as a technical advisor on the film—adjusting Meryl Streep’s rosary and showing her how to work the cape and all of that. I spoke to her class and at a couple of events for the Sisters of Charity, and started a new conversation with them. I have a renewed respect for the extraordinary lives of service that they’ve led.

Chapter 16: Theater bridges the gap between image and language. As a playwright and a director, do you consider yourself more of an image user or a language user?

Shanley: Certainly, I’m visual. That’s part of what I do; those are some of the materials that I draw on. But I would say I’m a philosophically based artist. I’m always writing and re-writing the operating manual by which I live based on past and present experiences and trying to formulate a guiding philosophy that serves me well.

Chapter 16: The Lipscomb event intends to stimulate dialogue regarding, in their words, “the captivating quality of the arts.” By this I assume they mean the formation of faith by attraction and the use of art as insight. What role does theater—or film, for that matter—play in faith?

Shanley: I think that film is traditionally where you go to see things you can’t see in your everyday life. So you get to see how the nuns live when they’re in the convent, because we don’t get to go in convents. It’s a safe way to do that. By doing that—whether it’s [visiting] the plains of Mongolia or a little blue-collar neighborhood in the Bronx—we broaden our understanding of what’s going on in the world, and I think that can only be helpful for understanding our own situation. It’s sort of like why writers during the age of Hemingway went to Paris to understand what went on in the Midwest.

Chapter 16: Some say that the church has relinquished its responsibility to use art in the service of spiritual formation. Do you see your own work as somehow making up for this deficiency?

Shanley: You can’t build on a deficiency; you have to have a firm foundation. A long time ago, when I was a kid, my teachers took me to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was a very down-the-line Catholic at that time—twelve years old. And we go in this room that has a Roman sarcophagus, which is heavily carved. I read the sign, and it points out to me that one of the [carved] figures is Jesus, but then all of the Roman gods were there, too. The guy who was put in this thing wasn’t taking any chances.

Shanley: You can’t build on a deficiency; you have to have a firm foundation. A long time ago, when I was a kid, my teachers took me to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was a very down-the-line Catholic at that time—twelve years old. And we go in this room that has a Roman sarcophagus, which is heavily carved. I read the sign, and it points out to me that one of the [carved] figures is Jesus, but then all of the Roman gods were there, too. The guy who was put in this thing wasn’t taking any chances.

That kind of broadness of spirituality has many names; faith in God has changed ten thousand times. But there is some kind of direct spiritual experience that does bear some visual signs and language signs. These things can be used to help maintain or to form a connection with spiritual things, and I am utterly ruthless in my quest to find a live line to the sky. If one of them isn’t working for me, I will try another until I find that one [image], or series of images, that connects me to my original spiritual experience.

Chapter 16: Do you think your audience at Lipscomb, a Church of Christ school with a conservative reputation, will be open to hearing that?

Shanley: We’ll see. I hope I don’t terribly offend anybody.

When I was a kid, they gave you the Old and the New Testament in a single book. They presented it as if the Old Testament was the preparation for the New Testament. In that sense, it’s sort of like that sarcophagus. I wasn’t taught, for instance, that before the arrival of Christ that there was no God. I was just taught that God had a different faith. Then around the time of Christ, something transformative happened to the operating philosophy of many, many people. That new idea gradually spread and was a very useful idea to many, many people—a civilizing idea, a helpful idea. It’s an idea that always goes away and always comes back.

For instance, people are stoned to death in stadiums in Iran, and I keep waiting for someone from that community to say Let he who is without sin cast the first stone. That would still be an act of extraordinary courage, and it would still be a new idea in that community, in that particular context. Of course, during the time of Suleiman the Great, there was a major cultural expansiveness going on in the Middle East, but at a certain point they stopped accepting expansion of thought and culture. It caused them problems, and certainly we should learn lessons from that.

Chapter 16: What first kindled your interest in theater?

Shanley: I saw two plays at the high school I went to, Cyrano de Bergerac and The Miracle Worker, and both of them just bowled me over. They were high-school productions but they were good productions. I never saw another play until I was twenty-two, and then I saw a slew of them over the period of a year or two. But I was always kind of a playwright because I was interested in dialogue. It spoke to me. I started off as a poet but I needed the right form, and the standard form for poetry turned out to be not the right one—I’m a much more social person than that. I’m interested in the collaborative arts, and I like the idea of creating a story that happens in a living way before you.

Chapter 16: What role does doubt play in faith?

Shanley: It’s absolutely essential, because doubt is the space that you leave to listen to other people. If you don’t have that, then you’re completely insular—there’s no way to reach you. I would say the effect of Jesus Christ as a speaker was to create doubt all around him.

Chapter 16: You titled your play, Doubt: A Parable, but parables are some of the most confusing stories in the Bible.

Shanley: I think there’s a reason for that. Certainly there’s a cultural reason for it, but there’s also the reason that a parable allows you to continue to talk about something. [The parables] don’t have simple moral, end of the story. If faith requires a leap, it means you’re leaping over something, and there’s no harm in naming what that is.

Chapter 16: Pope Benedict’s response to the child-abuse scandal seems to be long on forgiveness and apology but short on discipline and accountability. That hasn’t played well, even among Catholics. As an artist interested in issues of authority and the channels of power, what do you think his stance says about the current state of the church?

Shanley: I think that Pope Benedict has lost sight of the fact that the moral authority of the Catholic Church in the public forum is at this moment non-existent. When you do something very wrong, you must—and this is a tenet of the Catholic Church—admit what you’ve done, ask forgiveness, and do penance. I haven’t seen any penance. The Pope will say on one day that he’s very sorry for these things, and the next will preach to people about what is right and wrong. I would say you cannot do that. You really have to be quiet in terms of suggesting that people should listen to you. That’s an act of humility. When an institution such as the Catholic Church commits widely documented crimes against children and against their parents, it’s very important for them not to turn around the next day and say you shouldn’t wear condoms. You have to recognize what humility means on the earthly side of the equation. What you expect of your parishioners you should also expect of yourself.

Chapter 16: Speaking of humility, you took some critical heat for Joe Versus the Volcano. When it came time to direct Doubt, did that reaction change your approach to filmmaking?

Shanley: It couldn’t really, because Doubt is such a different kind of film. Joe is a very fanciful, fantastic story and is stylized for that reason, whereas Doubt is extremely grainy and realistic. When you do these things, whether it’s a play or a film, people hate some of them, and some of them they like. You have to try to be true to yourself and express [yourself] the best that you can, and then people are entitled to their reaction. Then you move on; you keep going.

Of course, the criticism that you take is something you have to weather and it batters you, but you’ve got to be tough to do this stuff. You keep writing about the new thing, because if you stay with the old thing, you’ve got no place to go. It’s great to have another script ready, so, as the thing that you’re doing is going down in flames, you can think Ah, yes, but the next one. … Certainly that will go well. I’ve written an extraordinary amount of stuff, and I try to get everything out there. In spite of that, I still feel the pain and everything, but now I’ve come to expect pain.

John Patrick Shanley will be in Nashville as part of Lipscomb University’s thirtieth annual Christian Scholars’ Conference. He speaks at 4 p.m. on June 3 in Lipscomb’s Collins Alumni Auditorium. A question and answer session will follow.

The conference will also offer a staging of Doubt, produced in collaboration with Tennessee Repertory Theatre, Actors Bridge Ensemble, Amun Ra Theatre, and the Nashville Shakespeare Festival. Starring Nan Gurley as Sister Aloysius and Steven Pounders as Father Flynn, Doubt will be performed June 4-6 and 11-13 in Lipscomb’s Shamblin Theater at 7 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays and at 2 p.m. on Sundays. Tickets can be purchased at www.lipscomb.edu/csc/public-events/ or by calling (615) 966-7609.