Emancipation Memories

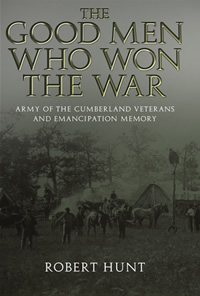

In Robert Hunt’s review of regimental histories, veterans of the Army of the Cumberland interpret the Civil War.

Recruits, mostly from Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, ultimately became the Army of the Cumberland as they marched south into Kentucky and Tennessee. The understood goal was to crush a rebellion promoted by radical secessionists. Few of these soldiers had any problem with slavery, and almost none would have applied the “all men are created equal” principle to blacks. As the war continued and intensified after 1863, however, their own experiences with freed slaves led them to reconsider. In The Good Men Who Won the War: Army of the Cumberland Veterans and Emancipation Memory, Robert Hunt, a professor of history at Middle Tennessee State University, traces and analyzes the infinite variations in how the veterans came to think of the Civil War in light of Northern victory and subsequent national history.

This book is aimed at serious students of the Civil War and late-nineteenth-century American history and historiography. In his prelude, Hunt brings others up to speed on the strategic aspects of the war before focusing on the literature that developed mostly afterward—as much as fifty years after. He relies not on the major primary and secondary sources that historians have used for generations, but on the writings of less well-known regimental historians and other veterans, such as the disillusioned carpetbagger, Albion Tourgee, who hoped but failed to remodel Southern economics and society on the Northern model; Wilbur Fisk Hinman, who wrote a novel detailing a young recruit’s life in the bottom ranks; and Joseph Warren Keifer, who became a prominent Republican congressman and proponent of a world-class American navy and the annexation of Cuba.

Considering the attitude of the writers at the beginning of the war, they came a long way. Of course, the army found itself engaged in practical abolition as they liberated slaves. “Anger at slave owners merged with disdain for the Confederate slave-owning society that fought against the Union, prodding the Cumberlanders during the war to free the captives of their enemy,” Hun writes. Yet Cumberland narrators, who “were more than eager to claim credit for every element of their victorious war,” admitted “that it had sometimes been difficult to move the men from practical abolitionism to support for the politics of emancipation. Hiding refugees, removing black workers from Confederate fields, or facing down defiant planters was one thing, supporting War Department and presidential policy was something else.”

Considering the attitude of the writers at the beginning of the war, they came a long way. Of course, the army found itself engaged in practical abolition as they liberated slaves. “Anger at slave owners merged with disdain for the Confederate slave-owning society that fought against the Union, prodding the Cumberlanders during the war to free the captives of their enemy,” Hun writes. Yet Cumberland narrators, who “were more than eager to claim credit for every element of their victorious war,” admitted “that it had sometimes been difficult to move the men from practical abolitionism to support for the politics of emancipation. Hiding refugees, removing black workers from Confederate fields, or facing down defiant planters was one thing, supporting War Department and presidential policy was something else.”

Only with the hindsight of many decades did the broader ramifications of the war become clear to them. For one thing, it demonstrated that an economic system based on the free labor of all classes, rather than one in which slave labor supported the idle classes, was ultimately more viable. “As Cumberland veterans described it later, the war that ended in 1865 freed and made dominant the North’s labor system … and placed the United State on a path to become a new kind of world power.” Because the North had finally fulfilled the nation’s “enduring mission” by ending slavery, it had a right and even a moral duty, to export its proven system to the rest of the world through benevolent expansionism.

Hunt’s epilogue points out, too, that the war and the North’s victory forecast the character of wars to come: like the Civil War, both World Wars were big and based on total national mobilization. And the ambivalent nature of victory became typical, as he points out: “At several points in America’s modern military history, we have organized overwhelming power and used it to destroy (or threaten) the immediate enemy, but ‘real’ victory has always remained elusive, fuzzy, or quickly redefined by circumstance.”