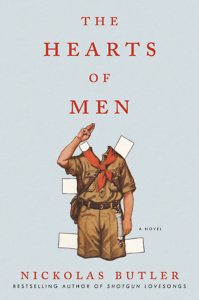

Embrace the Badness

In The Hearts of Men, Nickolas Butler stages the trials of Boy Scout camp

The title of Nickolas Butler’s new novel, The Hearts of Men, teeters on the brink of sentimentality, but it also points directly to the book’s thematic core—the way hearts can be instructed by experience, hardened by misfortune, and broken by love. Butler’s novel tests the fortitude of its characters and questions the strength of their attachments, but it also offers proof that it’s never too late to act on the edicts of your own heart.

The novel’s setting is at a stereotypical Boy Scout camp in northern Wisconsin. Camp Chippewa is where young men develop self-reliance and inner strength, but it’s also where the weak get stigmatized and abused and where amateur delinquents get first tastes of tobacco, booze, and pornography. Butler incorporates those conventional elements into his narrative and them pushes them to extremes, to points of crisis where adolescents learn what their hearts are capable of enduring.

The Hearts of Men consists of three long episodes at Camp Chippewa spread out over fifty years. In 1962, Nelson Doughty discovers that having just one friend, the older and more popular Jonathan Quick, isn’t sufficient to save him from the brunt of adolescent torment. Nelson responds to this discovery by toughening himself through military training and, eventually, tours of duty as a Green Beret in Vietnam. He returns, shattered and rudderless, to replace his old mentor as director of the camp. In 1996, when the now-jaded Jonathan Quick returns to the wooded camp himself, he is determined to disillusion his own idealistic sixteen-year-old son. Ideals like truth, honor, and love get put to critical test in the final section of the book, when violence invades the camp’s idyllic setting.

Throughout the novel, Butler creates tension between the Boy Scout code (trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly…) and the corrupt reality of actual camp life. Cynical Jonathan sees the Boy Scouts as “a dogged fraternity of paramilitary Young Republicans desperately clinging to some nineteenth-century notion of goodness.” His son, Trevor, wonders if scouting is pointless in a world that his father believes to be driven by selfishness and riven by greed: “What’s the point of all this if we’re just going to end up embracing the badness?” Trevor asks. A generation later, Jonathan’s grandson echoes that sentiment, calling the Scouts a “stupid paramilitary Christian fraternity … shooting guns and preparing for the damn apocalypse.” Only Nelson, it appears, has the mettle to uphold the Boy Scout standard.

Butler’s novel is filled with images of “badness.” Boys, malevolent outside the constraints of adult supervision, invariably resort to Lord of the Flies-level violence, especially when they can exploit the weak and outcast. Husbands physically dominate wives; fathers intimidate children. Men prey on women they cull and corner. Love desiccates until it becomes its opposite. War scars soldiers with life-long psychological wounds. Yet through it all Butler’s characters, familiar with the dark, strain instinctively for the light.

As a genre, the novel has always examined how characters, placed in difficult circumstances, make critical choices and then learn to live with the results. In Butler’s previous novel, Shotgun Lovesongs, a group of male friends confront the heartaches of youth and the compromises of middle age. They may have lost the fire of adolescent dreams, but beneath the veneer of maturity the old passions and losses continue to boil. In The Hearts of Men, Butler again explores the adjustments necessary to avoid a decline into despair, though the tone remains surprisingly hopeful in this book, as if his new characters believe redemption is waiting around the next corner.

As a genre, the novel has always examined how characters, placed in difficult circumstances, make critical choices and then learn to live with the results. In Butler’s previous novel, Shotgun Lovesongs, a group of male friends confront the heartaches of youth and the compromises of middle age. They may have lost the fire of adolescent dreams, but beneath the veneer of maturity the old passions and losses continue to boil. In The Hearts of Men, Butler again explores the adjustments necessary to avoid a decline into despair, though the tone remains surprisingly hopeful in this book, as if his new characters believe redemption is waiting around the next corner.

Though Butler specializes in men, this novel devotes long episodes to depictions of women, particularly Jonathan’s daughter-in-law, Rachel. She has experienced enough tragedy to earn her grim outlook—she refers to herself as “haunted”—but wants her son to know that the world still contains sublime beauty and sources of wonder. Rachel travels to Camp Chippewa to re-connect with nature and bond with her son before he leaves for college. Butler’s readers could have warned her that Boy Scout camp cannot shelter her from the horrors of the modern world.

The novel’s world-weary vibe verges on melancholy, but before his readers can drown in bitterness Butler reveals moments of grace that redeem existence and dangle the possibility of happiness. Nelson’s predecessor at the camp takes Nelson on a nocturnal quest to locate a secret herd of albino deer “bathed in lunar light” whose hides glimmer beside the reflected light of a secluded pond. Rachel wants her son to travel to South Africa to visit the Drakensberg Mountains, where hearts and meteors explode with equal violence and where she learned difficult lessons about self-determination.

When our lives appear devastated by death, a vestigial life instinct responds, in ways that commonly are labelled heroism. Butler shows us that courage consists simply of an individual heart finding out how much strength was stored away in its hidden vaults.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English in Nashville.