Employed by Truth

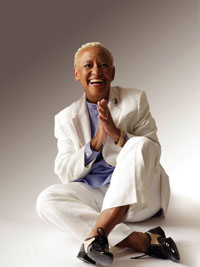

Poet Nikki Giovanni is still speaking her mind

Since she first gained attention in the late 1960s with fiery poems like “The Great Pax Whitie,” Nikki Giovanni has been one of America’s most popular poets. She has published more than a dozen books of poetry and another dozen titles for children, along with diverse works of criticism, social commentary, and memoir. She also has a slew of spoken word recordings to her credit, one of which—”The Nikki Giovanni Poetry Collection”—was nominated for a Grammy in 2004. Her popularity is matched by high regard for the artistic and social importance of her work. According to Helen Houston, professor of English at Tennessee State University in Nashville, Giovanni “follows in the tradition of those African American writers who called America to an accounting or attacked America for its hypocrisy.” She places Giovanni alongside writers such as Audre Lorde and Amiri Baraka.

For all her enduring literary prominence, however, Giovanni’s probably most widely known these days for her appearance at the Virginia Tech convocation ceremony on April 17, 2007, the day after a mass shooting on that campus took the lives of thirty-two students and faculty members. As a popular teacher at Virginia Tech for more than twenty years, Giovanni was a familiar presence to the university audience, but with her close-cropped hair and masculine suit and tie, she must have cut a surprising figure to many of the people across the country who watched the ceremony on television. After somber, conventional words of mourning and comfort from Virginia governor Tim Kaine and President George W. Bush, Giovanni strode up to the podium and launched into a lyrical chant that was more exhortation than elegy. Even as she rallied community spirit with a refrain of “We are Virginia Tech,” she placed the shooting within a global context of suffering and violence, encouraging her listeners to see beyond their personal pain.

We do not understand this tragedy

We do not understand this tragedy

We know we did nothing to deserve it

But neither does the child in Africa

Dying of AIDS

Neither do the Invisible Children

Walking the night away

To avoid being captured by a rogue army

Neither does the baby elephant watching his community

Be devastated for ivory …

The audience responded by chanting the school cheer (“Let’s go, Hokies!”), while Giovanni raised her arms in a victory wave. The moment was jarring, inspiring, and deeply moving, all at once. Asked in a recent email exchange about writing verse for such extraordinary occasions, Giovanni—who had taught the shooter, Seung-hui Cho, in a poetry class—is matter-of-fact: “You drive the bus. Your job is to be in the moment,” she says. “I was asked to respond to a very sad event. I took this as a wheel spinning. I tried to find a way to let that motion carry us forward.”

Virginia Fowler, professor of English at Virginia Tech, credits Giovanni with defining the community’s response to the tragedy: “It sort of set the tone for how the university was going to deal with it,” says Fowler. “Her speech really did give the university a direction, a way of responding to something that had pretty much overwhelmed everyone.”

Giovanni’s “We are Virginia Tech” address was in many ways a singular poetic event, and yet it was very much in keeping with Giovanni’s lifetime of writing passionately and “in the moment.” She has always written poetry shaped by personal experience—an experience thoroughly grounded in the zeitgeist. Born in Knoxville in 1943, Giovanni’s early years were divided between that city and an all-black suburb of Cincinnati, and she has vivid memories of segregation. She began to write in grade school, though she recalls her first attempt at writing poetry as “a disaster.” By the time she enrolled in Nashville’s Fisk University in the mid-1960s, black-power ideology was on the rise, displacing the gentler integrationist rhetoric of the early civil-rights movement, and Giovanni embraced it, assuming the combined role of activist and artist that has characterized her career.

Giovanni’s “We are Virginia Tech” address was in many ways a singular poetic event, and yet it was very much in keeping with Giovanni’s lifetime of writing passionately and “in the moment.” She has always written poetry shaped by personal experience—an experience thoroughly grounded in the zeitgeist. Born in Knoxville in 1943, Giovanni’s early years were divided between that city and an all-black suburb of Cincinnati, and she has vivid memories of segregation. She began to write in grade school, though she recalls her first attempt at writing poetry as “a disaster.” By the time she enrolled in Nashville’s Fisk University in the mid-1960s, black-power ideology was on the rise, displacing the gentler integrationist rhetoric of the early civil-rights movement, and Giovanni embraced it, assuming the combined role of activist and artist that has characterized her career.

According to Fisk’s University Librarian, Jessie Carney Smith, who joined the faculty during Giovanni’s student days, there were no major protests on campus at that time, but there was a mood of unrest among the students nonetheless. Smith remembers Giovanni as gifted and rebellious: “She was quite outspoken and liked to set her own rules. She liked to challenge authority.” In fact, she was expelled from Fisk for a time, not because of any serious infraction, but for defying policies she considered unreasonable—including, according to Smith, a rule forbidding female students to wear pants. After being readmitted, Giovanni channeled her energies into organizing rather than rebelling. She revived Fisk’s chapter of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and she served as editor of the campus literary magazine.

Within a year of leaving Fisk, Giovanni’s first book of poetry, Black Feeling Black Talk, was published, and it established her as an important voice in the growing Black Arts Movement, which sought to convey the African American experience through politically engaged art and literature. The poems in Black Feeling Black Talk, and in the follow-up collection, Black Judgment, remain some of Giovanni’s most popular and important verses. “Giovanni should be introduced through her early poetry,” says Helen Houston, when asked where readers should begin to acquaint themselves with the writer’s large body of work. Houston particularly recommends “Nikki-Rosa,” a poem written in the vernacular style that remains Giovanni’s hallmark. At once acerbic and nostalgic, the poem acknowledges the hardships of black childhood while reclaiming its particular joy from the standard liberal narrative of deprivation:

[A]nd I really hope no white person ever has cause

to write about me

because they never understand

Black love is Black wealth and they’ll

probably talk about my hard childhood

and never understand that

all the while I was quite happy

The poem from this period that most clearly displays Giovanni’s gift for capturing the spirit of the times is “The Great Pax Whitie.” It begins with the full force of black rage, which dominated both the political and cultural discourse of the day:

In the beginning was the word

And the word was

Death

And the word was nigger

And the word was death to all niggers ….

Behind the anger, however, is a vision of humanity that is a constant theme in Giovanni’s poetry, expressed here as a mythic image of maternal love:

While our Black Madonna stood there

Eighteen feet high holding Him in her arms

Listening to the rumblings of peace

be still be still ….

The radicalism of “The Great Pax Whitie” has long since been displaced by a gentler sensibility and a more personal focus in Giovanni’s work, but the writer has no desire to disavow what may still be her most famous poem. “It is a good poem. Clearly the poem of a young woman,” she says, “I am very proud of ‘The Great Pax Whitie.'”

The radicalism of “The Great Pax Whitie” has long since been displaced by a gentler sensibility and a more personal focus in Giovanni’s work, but the writer has no desire to disavow what may still be her most famous poem. “It is a good poem. Clearly the poem of a young woman,” she says, “I am very proud of ‘The Great Pax Whitie.'”

The evolution in Giovanni’s poetry is obvious in her most recent collection, Bicycles, which was just released in paperback. Though she continues to write largely in free verse, using natural language, her perspective has changed. She still devotes much of her work to describing the black experience, but her own experiences—including motherhood and a battle with lung cancer—have softened the anger that is so central to the poems in Black Feeling Black Talk. Here again, Giovanni seems to be in touch with the dominant feeling in the broader culture, which these days is more concerned with personal happiness and the importance of family than with revolution.

Giovanni’s poems have always had wit, but Bicycles is full of a lighthearted humor that is scarce in her earlier work. Troubled love is a frequent theme, and though she touches on the pain of soured romance, she often eases it with a dose of absurdity, as in “Letting the Air Out.”

This is more pitiful

than Polly

wanting a cracker

Or eggs that won’t sunny side up

Sadder than grits

that won’t boil

Or chicken wings

that stick to the skillet.

Even when Giovanni takes a political turn in Bicycles, she keeps her focus on the human factor. The sympathetic spirit of “We are Virginia Tech”—which is included in the book—also appears in poems like “Free Huey,” a celebration of the positive vision of Black Panther founder Huey P. Newton.

First there was the dream…though Huey wouldn’t call it that…Huey would say “A Ten Point Program” … “Power to the People” … But the people must dream …

Giovanni’s ability to express universal human experience within the context of her own strong black identity accounts for her enduring popularity, and Lean’tin Bracks, associate professor of English at Fisk, sees it as a core strength of her writing. As Bracks wrote in a recent email exchange, “The best thing about her work is its ability to be culturally rooted (the Black aesthetic) while lending itself to the journey of life that all persons experience. Her work proves that the Black aesthetic has no boundaries and that contemporary expression is best received when it honestly and directly explores life’s journey.”

“Our heritage is who we are; our ideologies are who we wish to be. If there is ever, to me, a tension between heritage and ideals, heritage wins.”

For Giovanni, the relationship between the generations, especially the education of the young, is a key part of that journey. At Virginia Tech, she chooses to focus on teaching undergraduates, who clamor to get into her classes. Smith, who has observed Giovanni’s appearances at Fisk over the years, says, “She likes young people, and they like her.” When Giovanni spent a semester as a visiting professor at Fisk in 2007, she visited local high schools to talk about the craft of writing and impressed the students with her openness. “It was pretty cool that she kind of treated us like we were sort of on the same level,” one Hillsboro High School student, who was not identified, told a reporter from News Channel 5 in Nashville.

In fact, much of Giovanni’s writing is directed to young readers. She has penned a great deal of poetry that celebrates childhood, and collections like Spin a Soft Black Song (1987) have become cherished classics within the black community. The New York Times Book Review described her children’s poetry as having the same “casual energy and sudden wit” as her adult work. Often, as in “Dance Poem,” its wit is intended for both parent and child.

tommy stop your tearing up

don’t you hear the music

don’t you feel the happy beat

don’t bite tony dance with me

mommy needs a partner

Giovanni is a passionate believer in the importance of teaching history to children, seeing it as far more important than any ideological training. “Our heritage is who we are; our ideologies are who we wish to be,” she says.” If there is ever, to me, a tension between heritage and ideals, heritage wins.” Much of her writing for children is devoted to conveying that heritage. Her children’s poetry is rich with references to African American history and to cultural heroes like Langston Hughes and Nina Simone. Her bestselling 2005 book, Rosa, about civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks, garnered multiple awards, and was described by Kirkus Reviews as “as essential volume for classrooms and libraries.”

Giovanni wants youngsters to gain a real understanding of the African American struggle, not as a fuel for anger, but as a model for their own lives. “Those older African Americans are great people,” she says. “They are the bridge over which we crossed. Our slave and Reconstruction ancestors are beacons of hope, faith, and perseverance to the world.”

On My Journey Now: Looking at African American History through the Spirituals, released in paperback last fall, gave Giovanni an opportunity to pay tribute to one of the great cultural achievements of those ancestors. In his foreword to the book, Arthur C. Jones of the Spirituals Project writes that Giovanni “employs her keen poetic vision to guide us through the inner world of the brave Africans in bondage who created the spirituals.” She brings that inner world to life by shaking history loose from stock narrative, depicting the past with an immediacy that will make adults as well as children appreciate the feeling that created these familiar songs. “We say that the slavers went to Africa to get the slaves,” she writes, “which is far from true. The slavers went to Africa to get the Africans to make them slaves. These were free people.”

“I have a job—writer—like any other job. I am employed by Truth.”

In addition to explaining the history of the slave trade and the institution of slavery that fostered the songs, she also speaks of her own experience with spirituals. She ties elements of slave history to particular songs, asserting, for example, that “Go Where I Send Thee” was used to teach slave children numbers, and “Were You There?” is actually about the execution of Nat Turner. She reminds her young readers that “Kumbaya” didn’t start out as a happy camp song but as a desperate petition to God by people in bondage. The book includes the lyrics to more than forty spirituals, offering a valuable reference for readers who didn’t grow up with them.

Giovanni’s most recent publications have her in critical mode, serving as editor for Best African American Fiction 2010, published in December 2009, and for The 100 Best African American Poems, due in April. Though she’s well into her fifth decade as one of America’s leading poets, there’s every reason to believe that Giovanni will continue to create abundant verse in the years to come—”I don’t believe in writer’s block,” she says.

Meanwhile, she is as outspoken as ever, saying in a recent interview with a Maryland newspaper that she would give Barack Obama “maybe a D plus” as president. “What makes him different from the obviously white presidents? Right now, nothing,” she said, noting that he has failed to keep his campaign promises to end the war and pass health care. It might seem a harsh judgment from the nation’s premier black poet on its first black president, but for Giovanni, failing to speak her mind would mean shirking the duty of her vocation. As she told Chapter 16 when asked about the artist’s place in society, “I have a job—writer—like any other job,” she says. “I am employed by Truth.”

[This article originally appeared on February 24, 2010.]