Empty Gyms

On basketball in a pandemic, private milestones, and a teary farewell to Paul Westphal

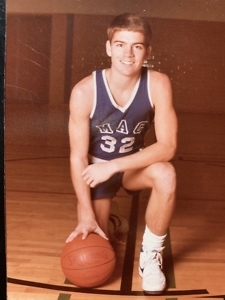

Most basketball is played in empty gyms. If you play, as I did, from youth leagues to middle school to high school — 11 seasons, all told — your practices outnumber games by a margin of hundreds. No fans see the endless lines you run, the torturous defensive slide drills, the shooting routines that rely on thousands of reps — nor, thankfully, do fans hear it when Coach* chews you out in front of the team for loafing or jacking around or failing to run the offense properly. Practice too is when you have breakthroughs: the first time you shoot a real jumper, touch the backboard, block a teammate’s fast break layup.

The highlight of my (otherwise undistinguished) junior year happened at the end of a practice when I dunked for the first time. My legs felt good that day, due to mysterious biorhythmic patterns every player recognizes. I’d been jumping higher, with greater ease, my hands reaching above the rim on rebounds, high on the square for layups. As practice drew to an end, my teammates started hyping me up. “Today’s the day, Kinch!”

The highlight of my (otherwise undistinguished) junior year happened at the end of a practice when I dunked for the first time. My legs felt good that day, due to mysterious biorhythmic patterns every player recognizes. I’d been jumping higher, with greater ease, my hands reaching above the rim on rebounds, high on the square for layups. As practice drew to an end, my teammates started hyping me up. “Today’s the day, Kinch!”

When Coach released us, the team gathered around one hoop to see if I could do it. These days, friends would break out mobile phones to record the moment, post it on Instagram to authenticate the experience. In 1985, the event was ephemeral — gloriously, spectacularly ephemeral. I remember that evening fondly, can still see my teammates grabbing their heads, whooping, running in circles. I don’t know how I looked — Did I smile? Was I stunned? But I remember how I felt: heroic. Lighter than air. And no one, outside our team, was there to see it.

Add to the countless hours of practice all the time you play alone, in gyms and on playgrounds — I don’t know how to estimate the total. As I’ve written before, playing by myself or with friends on the Gullett Elementary blacktop never felt lonely. Pete Maravich was there with me, Sidney Moncrief, David Thompson, and Julius Erving — Dr. J — were always there. When Paul Westphal passed away on January 2 this year, I shed private tears remembering how I tried to emulate his flashy style and burned to re-create his athletic feats. Westphal would angle his body and jet around defenders, a faster Jerry West, and then leap toward the goal, improvising his way past shot blockers, finishing with either hand. I practiced those moves endlessly, cheered only by the roars in my mind.

Westphal reached the pinnacle — NBA Championship with the Celtics in ’74 and the Finals with the Suns against his old team in ’76 — and heard his name chanted and his brilliance applauded in packed arenas, all the while going about his business with an expression of dopey detachment, his mouth opened in a perpetual “o.” My personal interpretation is that Westphal himself struggled to believe how awesome he was. Man, am I really this good? Is anybody? O, I don’t know. Long before he was the Suns’ star, the curly-haired, handsome off-guard with a surfer’s nonchalance, he spent hundreds of hours far from fans, practicing ball handling and fantasizing about playing like his idols: K.C. Jones, John Havlicek, Dave DeBusschere. Maybe he’s playing with them now.

Westphal reached the pinnacle — NBA Championship with the Celtics in ’74 and the Finals with the Suns against his old team in ’76 — and heard his name chanted and his brilliance applauded in packed arenas, all the while going about his business with an expression of dopey detachment, his mouth opened in a perpetual “o.” My personal interpretation is that Westphal himself struggled to believe how awesome he was. Man, am I really this good? Is anybody? O, I don’t know. Long before he was the Suns’ star, the curly-haired, handsome off-guard with a surfer’s nonchalance, he spent hundreds of hours far from fans, practicing ball handling and fantasizing about playing like his idols: K.C. Jones, John Havlicek, Dave DeBusschere. Maybe he’s playing with them now.

Watching the NBA this season makes me think of empty gyms not as unfortunate pandemic protocol, but as basketball returning to its purest state. Players love this game for its sensory pleasures — the soles’ squeaks, the concussive dribbling, the rip of shots passing through a nylon net (a beautiful sound that is poorly served by the onomatopoeic “swish”) — and for the prospect of competition. At the Y, grab four other guys and call “next” — do you need a crowd for that? Back in Austin during college breaks, my brother and I and our friends would head down to the Clark Field courts near the university and stay for as long as we could hold the court, Texas students passing by and blithely ignoring our brilliance. We weren’t bothered.

I’m not saying that having fans is a drawback. The NBA is a stage for the miraculous—Steph Curry’s 62 against the Blazers being the most recent reminder — and fans exponentialize the dramatic excitement of competitive games. The Mavs-Nuggets OT game on January 7, with Doncic and Jokic reminding us that top-level basketball is as various as the geniuses who play it, would have been a delight for Denver fans.

But when I see them and Jamal Murray (quickly becoming a personal favorite) playing like hell to beat each other and then smiling and embracing when it’s done, I remember pickup games at Stanford’s Wilbur courts, sometimes against varsity football players such as Ed McCaffrey (now known as Christian’s father) and Garin Veris (later a defensive end for the Patriots and to this day the biggest man I’ve ever tried to guard in the post — like defending an aircraft carrier). I imagine myself in 1987, mouth open to re-oxygenate before the next possession, thinking, Man, is life really this good? Is anybody’s? O, I don’t think so.

*My coach at McCallum High School, Don Caldwell, passed away in 2019. His obituary drew hundreds of responses on our school’s Facebook page, former players testifying to his influence on their lives. I miss him dearly.

Copyright (c) 2021 by Sean Kinch. All rights reserved. Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.