Eye of the Beholder

Ottessa Moshfegh discusses beauty, humor, and the ecstasy she finds in writing

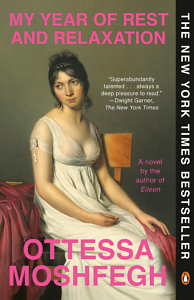

For the unnamed, privileged, and beautiful narrator of Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, the most promising cure for feeling out of step with the world around her is to undergo a yearlong, pharmaceutically induced hibernation. By manipulating her superbly incompetent psychiatrist, Dr. Tuttle, she obtains a regimen of pills that reduces “everything, even hatred, even love, into fluff I could bat away.” After this year, she hopes, she’ll be ready to rejoin the world, able to thrive.

Months of drifting in and out of sleep eventually lead to blackouts lasting days, during which her unconscious self seems to exercise a will of its own, behaving in increasingly odd ways. This unsettling development disrupts the ideal she holds for her inner life: “emotions passing like headlights that shine softly through a window, sweep past me, illuminate something vaguely familiar, then fade and leave me in the dark again.”

Moshfegh’s writing makes the opposite impact — a striking, indelible jolt. By turns provoking and enlightening, My Year of Rest and Relaxation speaks to our modern anxieties and absurdities, revealing what endures inside us no matter how we try to numb or distract ourselves. Moshfegh specializes in characters whose private idiosyncrasies and desires obstruct their ability to connect with an outside world that seems incomprehensible or banal. Mercifully, she animates these characters’ lives with wry, thorny humor.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which was released in paperback this summer, has earned widespread praise, having been named a New York Times Notable Book and Entertainment Weekly’s top-rated book of 2018. Her previous novel — the challenging and acidly funny noir, Eileen — won the Pen/Hemingway Award and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2016. She followed Eileen’s success with 2017’s uniquely satisfying story collection, Homesick for Another World. A new novel, Death in Her Hands, is slated for release in April 2020.

Moshfegh recently answered questions via email for Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Eileen calls herself “ugly, disgusting, unfit for the world.” By contrast, the unnamed narrator in My Year of Rest and Relaxation knows she is a blond WASP beauty, the cultural apex of enviable attractiveness. Beauty, ugliness — what roles do they play in defining your characters’ worlds?

Ottessa Moshfegh: The way someone looks in a novel can do a lot of work to describe the values and principles of a culture, as well as establish a point of view and a specific subjectivity in a narrator. If beauty really is in the eye of the beholder, what is actually being described is the eye through which we are given entrance to the story. So I think beauty and ugliness are mostly about defining the character’s relationship to the world.

Chapter 16: The narrator places herself into an irresistible tension between our impulse to numb ourselves to an abrasive world and that world’s relentless tendency to crash in on us. Life comes to get her, and the novel ends on a refreshing note of emotional lift. Did you know beforehand where her year of sleep would lead her, or were you surprised along the way?

Moshfegh: I was continually surprised along the way. And I feel the ending is troubling. Although it is an emotional lift — the hopefulness in seeing a character who has been so numb finally feel moved — it is also highly questionable that her year of sedation has really cured her spiritual malady. Some days I think, “She has survived and has seen the light,” and other days I think, “She has sufficiently damaged her brain so as to quell the terror of her existential anxiety.” Up to interpretation, I guess.

Chapter 16: No matter how bleak or perverse the characters or events in your fiction become, humor always seems to shine through, in just the right moments. Is humor something you especially prize in your work?

Chapter 16: No matter how bleak or perverse the characters or events in your fiction become, humor always seems to shine through, in just the right moments. Is humor something you especially prize in your work?

Moshfegh: Yes! It is miraculous when I can make myself laugh. I was a child of the 80s, and I think my sense of timing has been influenced by a lot of the comedians of that era. From Woody Allen to Eddie Murphy. I have always loved stand-up, too. So I guess being funny is innate. I don’t really put in any special effort to create what’s funny, it just occurs. What I’m working on now isn’t funny to me at all, so I wonder if — once it’s done — I’ll see the funniness in it. Sometimes the funniest stuff is the most self-serious…

Chapter 16: Your protagonists are capable of such extreme self-discipline, although they direct that extremity toward a range of unusual behaviors or punishing refusals. What does internal discipline mean to these days, and what role does it play in your writing?

Moshfegh: Discipline right now means having the psychic energy to block out all other voices but the voice of my mind talking to my narrator as I write. I’m less of an extremist now, but when I was writing My Year… I moved to Montreal for a month in January because I knew nobody and it was so cold, I knew I wouldn’t leave my apartment. It was effectual, but very lonely. I ended up moving back to LA and finishing the novel there.

Chapter 16: Perhaps by contrast, you also seem to write with great freedom. Does writing bring you greater freedom, or do you not relate to it in those terms?

Moshfegh: There is no greater ecstasy for me than in writing. It is my method for connecting to God, and as someone who keeps a great deal to herself, a method of escaping the prison of my own suffering. So it is freedom, yes. But I don’t come to the page with the desire to feel free.

Chapter 16: Now that you’ve been profiled and interviewed in prominent venues like The New Yorker, how have you come to view your public persona in relation to your own sense of self. Is there a friendly relationship between these personas, or is there friction?

Moshfegh: I feel so lucky that I can afford to spend my life writing, having to maintain a public persona is worth the cost of admission. So I accept the tribulations and humiliations. Whatever friction is there, it’s only evident when I’m hanging out with people who don’t know the real me. I think I am lucky in that I attract very kind and special people into my life personally and professionally. I also don’t read reviews! I try hard to keep an even keel…

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.