Faction Jackson

David S. Brown places Andrew Jackson in the partisan politics of his time

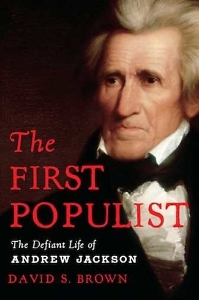

Donald Trump loves Andrew Jackson. While president, Trump tweeted about “Old Hickory,” laid a wreath on his grave, hung his portrait in the Oval Office, and even proclaimed that Jackson could have stopped the Civil War. Somewhat like Trump, Jackson was a populist hero who drew accusations of bigotry and tyranny. Yet as David S. Brown reminds us in his impressive new biography, The First Populist: The Defiant Life of Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States operated in the specific context of the first half of the 19th century, when he reflected and shaped the tensions that defined American politics.

Brown is a professor of history at Elizabethtown College. He is the author of numerous books on American politics and culture, including biographies of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry Adams, and Richard Hofstadter. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Why do you call Jackson “the first populist”? How did his policies and persona shape the politics of the early American nation?

David S. Brown: Jackson was the country’s first chief executive to come from neither Virginia nor Massachusetts — the traditional locus of political power. As the nation’s first populist president, he embodied the aspirations of a growing number of trans-Appalachian Americans, many of whom were actively participating in politics for the first time. They often held views on a range of issues — including economic development, Indian removal, and judicial authority — that were often at odds with East Coast pols. Jackson’s agrarian sympathies were part of a long era (1800-1860) in which Southern statesmen held the upper hand in Washington, an ascendancy only to end with the Civil War. His strongman mien — as a duelist, a conquering general at the Battle of New Orleans, and a president who vetoed more legislation than all his predecessors combined — was a defining feature of the man and part of his undeniable political charisma.

Chapter 16: There are many biographies of Jackson. What compelled you to undertake this project? What did you seek to add to the historical conversation?

Brown: Certain links between Jackson’s times and our own drew me to this topic. Deep divisions over questions of race, regionalism, and economic development tremored through America in the 1810s and 1820s, paving the way for Jackson’s presidency. In recent decades we have experienced a similar rising discontent. Jackson’s insistence on restoring the republic to its “true” constitutional principles, for example, might find contemporary pairing with the slogan, “Make America Great Again” — both cases bear evidence of a desire, not free from nostalgia, to deliver the country from presumed decline.

Chapter 16: As a biographer, you probe personal histories to explain stories of larger significance. What elements in Jackson’s background served to define him? How did his personality shape his politics?

Brown: In the final year of the American Revolutionary War, a 14-year-old Andrew Jackson was taken prisoner by invading British forces in South Carolina’s Waxhaws region. One of the fine-suited officers ordered young Andy to clean his mud-crusted jackboots. Insisting upon his right to be treated as a prisoner of war, Jackson refused, prompting the incensed officer to draw his sword and bring it down in the vicinity of the boy’s head — a blow Jackson deflected with his left hand, for which he received a serious wound resulting in a permanent scar. This unique incident — Jackson is the only president to be a POW — anticipated the confrontational style that so clearly defined his public career.

Brown: In the final year of the American Revolutionary War, a 14-year-old Andrew Jackson was taken prisoner by invading British forces in South Carolina’s Waxhaws region. One of the fine-suited officers ordered young Andy to clean his mud-crusted jackboots. Insisting upon his right to be treated as a prisoner of war, Jackson refused, prompting the incensed officer to draw his sword and bring it down in the vicinity of the boy’s head — a blow Jackson deflected with his left hand, for which he received a serious wound resulting in a permanent scar. This unique incident — Jackson is the only president to be a POW — anticipated the confrontational style that so clearly defined his public career.

Chapter 16: As president, Jackson claimed to act as the voice of the American people, and he disdained the power of elites. Yet he also built a stronger federal government and claimed more executive authority. How can we explain this apparent paradox?

Brown: Jackson insisted that, more so than congressmen and senators, as president he represented “the people,” and this justified his steep expansion of executive power — evoking for his critics the image of “King Andrew I.” States’ rights Southerners were concerned with the idea of a strong central government. In response to Jackson’s threat to deploy the U.S. Army to South Carolina if it failed to pay its share of the federal tariff (known as the Nullification Crisis), one North Carolina Democrat, speaking for many in his section, contended that “General Jackson’s proclamation will not satisfy the South.” But Jackson, the Tennessee slaveholder, knew that despite such concerns Dixie Democrats — drawn to the man who did so much to carve out a Southern cotton kingdom — would remain electorally loyal.

Chapter 16: Jackson is most notorious for his policies of Indian removal, employing both diplomacy and violence to drive Native Americans out of the southeastern United States. How did his contemporaries assess this aspect of his presidency? How should it shape our own understanding of Jackson?

Brown: Sides were divided on Jackson’s 1830 Indian Removal bill, which passed by a narrow 102-97 vote in the House of Representatives and 28-19 in the Senate. Certain Christian constituencies in the country were particularly incensed. For many years the removal policy made only a modest impact on the historiography; Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s 1945 Pulitzer Prize-winning Age of Jackson, to give but one example, ignored the topic, focusing on the Bank War as the centerpiece of Old Hickory’s presidency. But the removal program has much to tell us about race and regionalism, economic development, and the quest for a continental empire. Rather than confine this account to the 1830s, it might more effectively be framed within a broader context linking Jackson to a line of like-minded leaders including George Washington, another old Indian fighter and land speculator, who insisted that “the gradual extension of our Settlements will as certainly cause the Savage, as the Wolf, to retire.”

Chapter 16: Jackson hailed from Tennessee, a slaveholding state, and he enslaved African Americans at his estate, the Hermitage. As president, did Jackson preserve and promote the institution of slavery? Did he shape the budding sectional crisis that would lead to the Civil War?

Brown: Jackson perhaps did more to “preserve and promote the institution of slavery” prior to his presidency. As a general, his efforts during the War of 1812 to reduce both British and Native American power in the old Southwest (via the Battle of New Orleans and the Creek War) opened this region to an emerging Deep South — an area that would become known as the Cotton Belt. Jackson’s presidential removal agenda resulted in the expulsion of some 60,000 self-governing Indians and their replacement with a plantation economy based upon enslaved labor.

Chapter 16: Why does Andrew Jackson continue to inspire popular fascination? What is his legacy for today?

Brown: Jackson’s legacy has proven useful to various constituencies over several generations. In the late 19th century, Midwestern scholars emphasized his role as a democratic figure who broke the grip of East Coast political power; in the 1930s Depression era, Democrats extolled his efforts in the Bank War as something of a forerunner to the New Deal. Today, in the shadow of the long civil rights movement, Jackson is more often associated with slavery and Indian removal. Whereas he once ranked in the top 10 in historical rankings of presidents in polls conducted by such outlets as Siena College, C-SPAN, and The Wall Street Journal, he now lingers in the late teens and low twenties. Amazingly, he has played the roles of both hero and antihero — suggesting that in assessing Jackson we see in him a symbolic figure, one today amendable to both sides of our current, contentious “culture war.”

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.