Farewell, Sammy

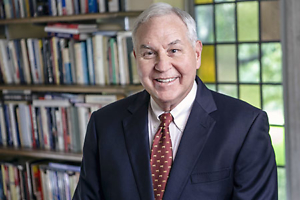

Tracey Davis talks with Chapter 16 about the last days of her famous father, Sammy Davis Jr.

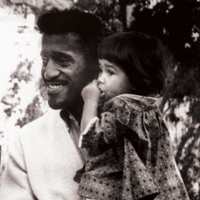

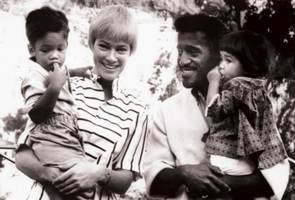

By his death in 1990, Sammy Davis Jr. was one of the world’s most recognizable personalities. A dancer, singer, actor, musician, and comedian, he lacked Belafonte’s good looks and Sinatra’s savoir-faire, but he had determination. Dropped into show business at age four, he knew no other life, and he worked extremely hard at it. Davis was a family man, but his breakneck schedule left little time for family. During his sixties, however, throat cancer finally slowed Davis down, and he was able to reconnect with his adult daughter, Tracey, born during his marriage to Swedish-born actress May Britt. These intimate discussions, during which Davis ruminates on his career and tries to reconcile being an absentee father, make up the bulk of Sammy Davis Jr.: A Personal Journey with My Father, Tracey Davis’s memoir about her dad’s final days.

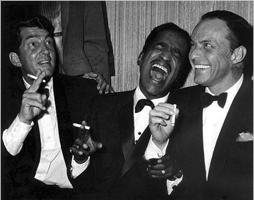

What emerges from the book is an image of Davis that’s quite different from the one in the glitzy photos with fellow Rat Pack members Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin that accompany this volume. Sammy Davis Jr.: A Personal Journey with My Father describes a caring and thoughtful man who never had time for the family he dearly wanted. Tracey Davis discussed her book in a recent phone conversation with Chapter 16.

What emerges from the book is an image of Davis that’s quite different from the one in the glitzy photos with fellow Rat Pack members Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin that accompany this volume. Sammy Davis Jr.: A Personal Journey with My Father describes a caring and thoughtful man who never had time for the family he dearly wanted. Tracey Davis discussed her book in a recent phone conversation with Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: How did you come to live in Middle Tennessee?

Davis: I’ve lived here for a little bit. The short story is I got divorced in Williamson County, and I have children. I came here from Los Angeles. I had married a gentleman who was the strength-and-conditioning coach for the Los Angeles Lakers. We moved up here, and here we sit.

Chapter 16: Your father famously said that as a “short, ugly, one-eyed, black Jew,” talent was all he had. It sounds like he also had drive. Was your father an ambitious man?

Davis: I’d absolutely say that was correct. You know talent will get you so far. But you have to factor in the times. Doing a YouTube video and someone liking it a hundred times—there was none of that. So you had to really dig down deep. You started with small clubs, and you kept going. You had to have drive and ambition. He had the talent, but you had to have the drive, especially being a black person in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, you had to.

Davis: I’d absolutely say that was correct. You know talent will get you so far. But you have to factor in the times. Doing a YouTube video and someone liking it a hundred times—there was none of that. So you had to really dig down deep. You started with small clubs, and you kept going. You had to have drive and ambition. He had the talent, but you had to have the drive, especially being a black person in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, you had to.

Chapter 16: You describe your father and his show-biz generation as “general practitioners”––they could sing, dance, act, and tell jokes with equal skill. Is there anyone in the contemporary entertainment scene who fits this description?

Davis: I’m a huge fan of Pharrell Williams. He’s fearless in terms of what he wants to do and what his vision is, which is part of his whole game. But if you’re talking about an all-around guy who can do a little bit of everything, Neil Patrick Harris comes to mind. Because he’s funny, he can sing, he can dance, he can act. And who doesn’t love Neil Patrick Harris? If you watched the Tony Awards, the guy’s hilarious. But “fearless,” that’s one of the words that I would use to describe my dad.

Chapter 16: Your father was close to Martin Luther King Jr. How did he feel about the more radical members of the civil-rights movement, say Stokely Carmichael or Malcom X?

Davis: In every great—I don’t want to say revolution because that may have the wrong connotation. But when a big change comes, there’s always an agitator. Someone who sticks their nose out a little bit too far, and some kind of combustible thing that happens. Martin Luther King was in my dad’s wheelhouse, and he respected him immensely—I don’t know anyone who didn’t. But it was a very hard time to figure out where your alliances were because everybody was fighting some kind of struggle, and just because he might have agreed with someone on one point, it didn’t mean that he agreed with his whole agenda. So it was more like picking and choosing—except for Martin Luther King, whom he was behind 100 percent.

Chapter 16: Did your dad ever want to take a more active role in politics, as Harry Belafonte and Frank Sinatra did?

Davis: Dad was behind JFK, obviously, and worked tirelessly to move the black community into his column. But Dad got snubbed by him at the inaugural, and that really hurt his feelings. I think the difference was that with the Kennedys there was the whole glamor thing. You never thought about them as down in the trenches doing the grunt work. Later on, my dad supported Nixon. Gave him a big hug and still was hearing about it thirty years later. Nixon treated my dad well and had some good ideas at one point. He invited dad to spend the night in the White House, which was a huge honor. The Nixon library asked me if I wanted to come down and do a book signing. For better or worse, they really were kind to my father.

Chapter 16: Were your father’s finances in good shape when he died?

Chapter 16: Were your father’s finances in good shape when he died?

Davis: I think that what happened to my dad is what happened to a lot of black performers that were coming up at the same time. There wasn’t anybody that was very forward thinking in terms of Let’s categorize everything, Let’s put everything somewhere, Let’s inventory everything, Let’s get a hold of this. Don’t take the money now; do it later; take it in this way, and all those kind of things. Because what happened to black performers a long time ago was that you wanted to take your payday because, gosh darn it, you couldn’t even vote, so you wanted to take your payday and get it, because two years from now they might change the rules so that you’re not entitled to anything. For performers coming up at that time, you wanted cash on the table. You weren’t thinking forwardly. My dad was mismanaged, absolutely. And I’ve been fighting the good fight to corral his stuff and get it to a good place. But did he take care of us; of course he did. We weren’t hurting. My mother wasn’t hurting. But in terms of How do we build a legacy? That was hurting.

Chapter 16: Did you ever consider performing yourself?

Chapter 16: Did you ever consider performing yourself?

Davis: I think I have a pretty good singing voice. My daughter, Montana, has an excellent singing voice. She’s a singer-songwriter. She’s twenty, and she’s up and coming. But I didn’t really ever think of it as a career. I like being behind the scenes. I like figuring out what’s going on. I’ve been a producer for a long time, and that’s where my niche is. I like to be behind the camera.

Chapter 16: Of your father’s legendary friends, which one left the biggest impression on you?

Davis: Uncle Frank. He was bigger than life, and he was over at Dad’s house a lot. When I got married—when I married my older kid’s dad—Frank came to my bachelorette party. It was me and my dad and my girlfriend and one of the McGuire Sisters and Uncle Frank. We sat backstage at the Nugget, sipping champagne and talking until five o’clock in the morning, and that was my bachelorette party. To this day it’s one of the best nights of my life. The stories that were told, and the laughing and giggling. The off-color jokes. My dad told this one on stage, too, so I don’t mind retelling it here. He said he had wanted to join a country club in Los Angeles, and his friend called and said, “I’m sorry, we can’t let you in.” And Dad said, “I know. It’s because I’m black.” And he said, “No, it’s because you’re a Jew.” He told it to me again at the end when he was sick. He just had this way of disarming you. Funny things that could have really stung him––really did sting him. He wasn’t Teflon, but he felt like he could laugh about it. He couldn’t let it bring him down. It wasn’t going to stop him. Little things like that—they never rose to the level of Uh-oh.

Chapter 16: It sounds like he was a sensitive man, though.

Davis: Heck yeah, he was. He had this really huge heart. And he was funny, and he was kind. Towards the end, when I’m pregnant and he’s dying, we had these great father-daughter moments that I’m so grateful for. We got to say goodbye, and that was a gift in itself. Then it’s over, and you’re like, Holy cow, but being able to say goodbye and spending all that time with him. That was priceless.

Chapter 16: With his schedule, I’m surprised he had time to say goodbye.

Davis: It was ridiculous. It was 1990 or 1989, and he’s still doing forty weeks a year on the road. But he loved it. And the beauty of it was, when he got to that level, it wasn’t these one-night things. You had time to sit down and enjoy whatever audience you had, and it was easier. But I don’t think he knew anything else. If he was home too long, he got antsy.

Paul Griffith is a freelance writer/musician based in Nashville whose interests include popular culture, religious history, and food and dining. Paul’s drumming can be heard on recordings by k.d. lang, Todd Snider, and many others.