Feathers and Hammers

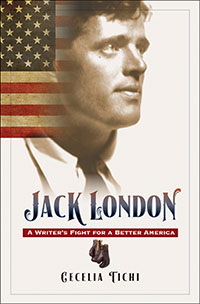

Cecelia Tichi paints a portrait of Jack London as a champion of progressive causes

Jack London was not particularly tall or particularly stout, but he was big—ambitious and adventurous, a dashing figure with thick, dark hair and dancing eyes. He loved boxing because it offered stark physical challenges and intricate strategies. Before catapulting to fame as an author and journalist at the turn of the twentieth century, he had sailed the Pacific on a seal-hunting schooner and sought riches during the Alaskan Gold Rush. In the words of one contemporary, he was “all sweetness and ferocity.” Those traits would help define his political stance in an era of class inequality and rampant exploitation. As Cecelia Tichi persuasively contends in her important new book, Jack London: A Writer’s Fight For a Better America, London was a powerful and effective voice for reform, serving to dull the sharpest edges of Gilded Age capitalism.

Tichi, a professor of English and American Studies at Vanderbilt University, argues that historians and political scientists have not seen London as an influential social critic, “mainly because they do not recognize literary figures as public authorities on matters of public debate.” But as Tichi points out, London had an extraordinary reach with readers, both men and women, of the working and middle classes.

Tichi, a professor of English and American Studies at Vanderbilt University, argues that historians and political scientists have not seen London as an influential social critic, “mainly because they do not recognize literary figures as public authorities on matters of public debate.” But as Tichi points out, London had an extraordinary reach with readers, both men and women, of the working and middle classes.

Driven to write a thousand words a day, London developed an energetic style and entertaining plots that appealed to a mass market. He produced novels and short stories, undercover exposes and battlefront journalism, dispatches about travel and sports, and much more. He profited from an emerging culture of American abundance even as he promoted the increasingly respectable socialism of the early twentieth century. He identified laissez-faire capitalism as the cause of widespread suffering among the poor and powerless.

London himself grew up in modest circumstances and identified with the working class. Before thriving as a writer, he worked in a cannery, a laundry, and a jute mill. His fiction thus critiqued the class system at home—sometimes with a feather, sometimes with a hammer. In his famous 1903 novel, The Call of the Wild, the protagonist is a sled dog that’s beaten and neglected by inept humans in search of wealth. Alert readers could draw parallels to the plight of poor workers in the industrial capitalist system. In London’s more controversial 1909 novel, Martin Eden, a working-class sailor wills himself into becoming a great writer but is alienated from big-time publishers and bourgeois society.

London also brought attention to the exploitation wrought by war and empire. Though he had supported the 1898 Spanish-American War as a civilizing mission, he changed his outlook after reporting on the mass death and senseless destruction of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. In 1907 he sailed across the Pacific with his wife, Charmian, and a small crew, inspiring a set of stories that explored labor tensions in the South Seas. These stories include exotic depictions of natives—without a doubt, London was steeped in the white supremacy of his era—but also expose the cruelties of the plantation system.

London also brought attention to the exploitation wrought by war and empire. Though he had supported the 1898 Spanish-American War as a civilizing mission, he changed his outlook after reporting on the mass death and senseless destruction of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. In 1907 he sailed across the Pacific with his wife, Charmian, and a small crew, inspiring a set of stories that explored labor tensions in the South Seas. These stories include exotic depictions of natives—without a doubt, London was steeped in the white supremacy of his era—but also expose the cruelties of the plantation system.

On the same tour, London was hosted by the wealthy businessmen who had brought about Hawaii’s 1898 annexation as an American territory. While taking advantage of his hosts’ hospitality, Tichi points out, London also noted their poisonous effects on the idyllic islands. His short story “The House of Pride” features, as Tichi writes, “a bloodless, self-righteous, repressed, thirty-five-year-old white prude of a banker and sugar baron who owns plantations and a railroad but is temperamentally cold and spiteful.” London’s sympathies lay with the workers in the cane fields, the lepers, the Hawaiians sacrificed at the altar of mass agriculture and tourism.

Throughout his writing life, London’s personal experiences kept motivating his progressive stance and shaping his popular novels. After buying a California property called Beauty Ranch, for example, he learned about the devastation wrought by planting a single crop and exploiting the soil—and his 1912 novel, The Valley of the Moon, champions sustainable farming. This pattern of advocacy for progressive and socialist reforms continued until his death in 1916, at the age of forty. “Like all prizefighters, he battled time and his own body,” writes Tichi. “Jack London was in the ring to the last, his punch thrusting straight and true through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.”

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.