Fertile Ground for Art

Suzanne Stryk’s The Middle of Somewhere travels outward and inward

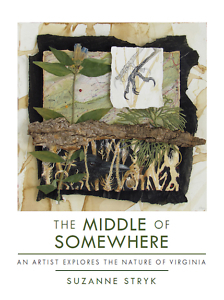

It’s said that to travel outward is to equally travel inward. This adage rings true in Suzanne Stryk’s The Middle of Somewhere: An Artist Explores the Nature of Virginia as we accompany her across the varied topography and history of the state. From 2011–2013, Stryk, who received a Master of Arts degree from East Tennessee State University, undertook a project to put a modern spin on Thomas Jefferson’s seminal Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), collecting, documenting, sketching, assembling, birthing the final extraordinary series of paintings — all with the eye and heart of a naturalist and the wonder and doggedness of a New World explorer — now housed at the University of Virginia.

Over these two years, Stryk visited Virginia’s five geological regions: Coastal Plain (Tidewater), Piedmont, Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge, and Appalachian Plateau. Her mantra: “There is no such thing as the middle of nowhere. Every place is the middle of somewhere for some living being.”

Although Somewhere is a companion to her original Notes series, this standalone flowering of Stryk as a writer deepens her artist’s perspective (and ours) far beyond the original project. The current work leads us through mosquito clouds, dusty barns, icy streams to see, really see, the source, the complicated history, the caught breath, the revelations — and the questions — that inspired Notes. She invites us to witness flow and change, the endangered and the enduring, the gone and the going away.

Note: I’ve known and loved Suzanne Stryk’s brilliant artistry for about 25 years and am grateful to call her friend. I’m privileged to own two of her paintings, one of which she created as the cover for my third poetry collection, Bound (Wind Publications, 2011). Also, I copyedited the manuscript of The Middle of Somewhere before it found a publisher. Suzanne Stryk answered questions for Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: On the idea of seeing, you write, “What matters is seeing freshly. …Which means seeing like a child.” You’re married to poet Dan Stryk, and poets often note the essential quality of paying attention. Have your years of living with a poet enhanced your own tendency to pay close attention, especially to the least of us in the natural world, like dung beetles and skinks?

Suzanne Stryk: What an interesting question. My close attention to small lives — those dung beetles and skinks you mention and a whole array of small critters — has roots in my girlhood. I kept mice and turtles as pets but was also fascinated by wild things. When I was about six years old, I remember finding a stag beetle in a window well. Those big pinchers! I was awed. But I feared telling friends about it — why? Because a “meh” or a “yuk!” response would have been so deflating.

No such deflation when sharing observations with Dan. No one is more interested in the latest painting on my easel or bug on my drawing board. But it’s symbiotic. Just yesterday he noticed that a suggestive shape on a magnolia leaf looked like a Paul Klee face. He propped it up in our kitchen window — just like in the chapter “Daily Observations.” And he shares poems with me, poems rich with perceptions. So in this way living with a poet has enhanced my artistic life, and as you say, my paying attention.

Dan and I both love a passage in the naturalist-writer Loren Eiseley’s The Immense Journey when he’s looking at a frog’s eye imagining how the frog sees. He writes, “This is the most enormous extension of vision of which life is capable: the projection of itself into other lives.” In the chapter “World Enough,” I wonder about how a raven sees the world.

Chapter 16: You often use maps in your paintings, in particular U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topographic maps, on which you overlay your collected assemblages. In Somewhere, you write, “These maps recall a living animal,” with the “hollows of a body, blue rivers and red roads like veins.” In fact, you call yourself a cartographer in the book, which evokes the idea of making the path as we go. Discuss your fascination with maps and how they guide your work, how they fix or expand it in a particular place or history.

Chapter 16: You often use maps in your paintings, in particular U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topographic maps, on which you overlay your collected assemblages. In Somewhere, you write, “These maps recall a living animal,” with the “hollows of a body, blue rivers and red roads like veins.” In fact, you call yourself a cartographer in the book, which evokes the idea of making the path as we go. Discuss your fascination with maps and how they guide your work, how they fix or expand it in a particular place or history.

Stryk: As a teenager in the 1960s, I took a train from Chicago to attend an ecology workshop down in Southern Illinois. After the staff took my suitcase, they gave me and two other campers each a compass and a topo map, a few tips on orienteering, and dropped us off in the woods, which seemed like miles away. We had to figure out how to get to camp! I experienced an intense feeling of being lost while finding my way — could anything be more like life than that?

So early on, I saw maps as both practical guides and as beautiful metaphors for our experience of life and art. In the preface of Somewhere, I write that a map’s “merger of the factual with the evocative plucks a chord deep inside me.”

Chapter 16: A finished piece of art from the Notes series begins every chapter in Somewhere, and your sketches and ink drawings appear throughout the book. As such, you are our personal guide in your journey across Virginia’s mountains and waterways, and even millennia before the present. Describe the relationship between the written narrative and the images, an interplay that makes the book unique.

Stryk: Somewhere is unique in that the artwork came first, the writing second. It’s really a hybrid book — equally art and creative nonfiction. The designer, Rebecca Davison, made that happen by organically embedding drawings into the text. Such as when I mention a black snake in “The Green Fuse,” that little snake slinks in the margin of the page.

I occupy an unusual niche artistically in that my assemblages are contemporary and conceptual, whereas my sketchbook drawings belong to a naturalistic tradition of recording observations. You’ll find ideas about art throughout Somewhere, but the chapter “Nest Making” is a stand-alone piece about the art-making process. For example, in it I write, “[T]he sense of inevitability is what all artists are after … whether an artwork took two hours or two years to create, whether it’s figurative or abstract, whether created with traditional oils or with a mash-up of materials, it must hold together as if it were destined to be that way.”

Ditto for writing. And I only recently realized that each chapter of Somewhere is like an assemblage. Because each chapter layers art, nature, history, and travel with childhood memories and philosophical wanderings.

Chapter 16: I visited your studio in Bristol, VA, during the creation of your original Notes project, and now I hold and treasure Somewhere, a tangible outgrowth of that project. You took a huge leap in writing about your exploration and discoveries. Can you describe the process of compiling and writing the book?

Stryk: I only began writing Somewhere when my Notes on the State of Virginia series was installed at the Taubman Museum of Art in 2013 — the first exhibit to begin the statewide tour. Driving back from Roanoke after the opening, I remember wishing I could share more of the backstories behind the artwork.

So I decided to give it a go. Fortunately, I’d made scads of notes during my travels and in the studio. Those along with my maps, books, and sketches gave me more than enough material to aid my memory. Every morning for months, I’d scribble thoughts about each place on a long yellow legal pad — I kept it messy trying to escape my inner editor! Then came the task of typing it on the computer, honing what to leave out, and what to expand. Working on the chapter “The Dinosaur and the Bridge,” I wondered how to convey information about Natural Bridge without it being a boring story-stopper. I had an “Aha!” moment when I realized I could have the lively guide speak. From then on, I really enjoyed writing dialogue and describing characters.

Chapter 16: Somewhere addresses such topics as mountaintop removal, ecological uncertainty for mussels on the Clinch River, and the moral complexities of Thomas Jefferson’s life and his philosophy. Did your decision to include controversial subjects give you any pause or problems in this state-sponsored project?

Stryk: The challenge was to strike the right balance. I believe love for the living world is what makes a difference in our lives and the planet’s fate. So I didn’t want to get too grim about problems. And I wanted to acknowledge people who are making a positive difference. Here’s how I tackled an environmental catastrophe in the chapter “World Enough”: “Odd how we seesaw between destruction and preservation: one person spills lethal chemicals into the river, killing all life for seven miles, and another dedicates a lifetime restoring that life to the river.”

I dealt with the paradox of Thomas Jefferson by asserting his biocentric insights while stating his moral failures. But what good does that 20/20 hindsight do unless we clean up our act? So from Jefferson I shift to our own moral failures regarding the planet, ones that future generations will judge us for. At the end of “Refuge,” I write, “we’re all dodging the reality of who or what’s been exploited to provide for us.”

Chapter 16: To end, you say that art is a way of knowing. Yet, you add, “Art embraces mystery,” saying you thrive in the zone between both. We all must live with ambiguities in our lives and find a way to be comfortable within/despite them. Can you expand on art and mystery in both visual art and writing?

Stryk: I’m astonished by what science tells us about the natural world. Yet as you point out, I love the ambiguous zone which leaves room for wonder, mystery, and humility — fertile ground for art. I mentioned wondering how a raven experiences the world — science can’t answer that even though it can tell us amazing facts about the bird.

What you’re asking isn’t easy to pin down. I’ll try to answer by talking about a specific image, my assemblage titled Flyway. Layered over a map is a vortex of feathers that come to a point over an egg painted with northern and southern hemispheres. While that alludes to the magic of migration (how do birds find their way?), the image also suggests our own life experiences.

How? There’s a clue in the last lines of the chapter “Flyway” after I’ve surprised hundreds of waterfowl in a marsh. I write, “I’d frightened them into a whirring frenzy as they refueled for the next leg of their journey south. I froze, a still point amid a dizzying vortex of feathered life.” So while I’m standing in a whirlwind of wings, I’m also suggesting a state of mind. A mysteriously fragile state of mind trying to be centered in a world of change and the “dizzying vortex” of life.

And may I tack on one more comment here? I think you can see now how Somewhere might appeal to those who never plan to set foot in Virginia. It’s about so much more.

Poet, playwright, essayist, and editor, Linda Parsons is the poetry editor for Madville Publishing and the copy editor for Chapter 16. Her sixth poetry collection, Valediction, is forthcoming from Madville in June 2023. Five of her plays have been produced by Flying Anvil Theatre in Knoxville, Tennessee. She is an eighth-generation Tennessean.