Finding L.A.

Rosecrans Baldwin tries to make sense of Los Angeles

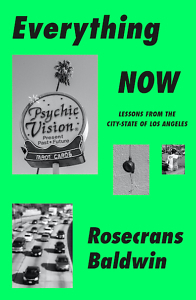

Author of two bestselling novels, as well as the widely acclaimed memoir Paris, I Love You but You’re Bringing Me Down, Rosecrans Baldwin turns to nonfiction with an essay collection. In Everything Now: Lessons from the City-State of Los Angeles, Baldwin grapples with defining the second largest urban entity in the U.S.

The seven chapters in Everything Now are broken into bitesize micro-essays and titled to resemble the experience of passing signs on L.A.’s freeways: “Lesson 1 / Anything Can Happen at Any Second”; “Lesson 2 / To Be a Somebody Without a Something Is to Be a Nobody”; “Lesson 3 / Some Are Footloose, Some Are Barnacles”; and so on.

The seven chapters in Everything Now are broken into bitesize micro-essays and titled to resemble the experience of passing signs on L.A.’s freeways: “Lesson 1 / Anything Can Happen at Any Second”; “Lesson 2 / To Be a Somebody Without a Something Is to Be a Nobody”; “Lesson 3 / Some Are Footloose, Some Are Barnacles”; and so on.

Baldwin, who spent part of his childhood in Nashville, commits himself to unearthing a language or framework that will make sense of the city. As the book’s subtitle suggests, this leads him to an old concept: the “city-state,” like Athens, Florence, or Sparta. A city-state, by most definitions, has an identifiable center with territories and possesses a level of sovereignty. But the further you read in Everything Now, the more Baldwin’s argument for the term starts to feel like shoving a square peg through a round hole. He notes writer and futurist Geoff Manaugh’s observation that “L.A. has multiple cores and is all periphery” and admits L.A. doesn’t really fit the essential criteria. It also isn’t financially self-sustaining. David L. Ulin is quoted as saying L.A. is sprawling and shapeless “like a vast amoebic mass” and any attempt to define it is to miss the point. Yet, if not for Baldwin’s relentless clinging, city-state might work, less as a classification than a metaphor, but the more he shoves, the less persuasive he is.

However, when Baldwin finally lets the story, much like the city, unfurl itself to its own liking, something incredible happens — a magic that can only be found wandering L.A.’s streets, neighborhoods, and underpasses. As he meditates on the stories and people that make Los Angeles unique, he creates something breathtaking and comes close to capturing the shapeless amoeba that is L.A.

Transformation, or at least the possibility of transformation, seems to be at the heart of what defines Los Angeles. In the book’s second chapter, Baldwin writes of posting an ad online for anyone interested in talking about loneliness and receives answers ranging from the predictable sexual propositions and nude photos to people sharing their experiences of emptiness. “Everyone is looking for a better offer,” one man responds. “It’s a happening spot. So many events and wonderful things to experience — but with someone,” writes another. The multifaceted sense of vulnerability, of bodies, of words, of emotions, touch on something significant — like a pebble plopped in a pond, with L.A. as the ripples left behind.

Transformation, or at least the possibility of transformation, seems to be at the heart of what defines Los Angeles. In the book’s second chapter, Baldwin writes of posting an ad online for anyone interested in talking about loneliness and receives answers ranging from the predictable sexual propositions and nude photos to people sharing their experiences of emptiness. “Everyone is looking for a better offer,” one man responds. “It’s a happening spot. So many events and wonderful things to experience — but with someone,” writes another. The multifaceted sense of vulnerability, of bodies, of words, of emotions, touch on something significant — like a pebble plopped in a pond, with L.A. as the ripples left behind.

In the same chapter, Baldwin describes a tennis partner of his named Freddy, a lawyer with a nice car and apartment. Freddy is also an amateur photographer, often showing Baldwin naked and lewd photos of aspiring models before or after their match. Nevertheless, Freddy is “tenderhearted” and somewhat defensive about the photographs, always at pains to say that the women posed for him “quite willingly.” Baldwin writes:

Women would arrive late at night. Freddy arranged different setups, “little pools of light around the loft.” … The models and Freddy didn’t always have sex, he said, but that didn’t matter; the moment’s purpose was transformation, of Freddy from lawyer to artist, of model from aspiring to professional, two humans lofted above the city, spotlighted for a moment, making themselves into their finer selves. “It’s a process,” he said contemplatively. “The journey is really amazing to watch.”

By the end, you are wondering who the true Freddy is. Is he the lawyer? Or the tennis player? Or is he just a playboy flaunting naked photos of models on top of him in the bath? Is the love for the art at the end of Freddy’s story real? Is he the artist who loves to see the flicker of potential become a flame? Because it is Los Angeles, all Freddy’s identities are true, and also none are true at all.

Baldwin exceeds all expectation in these small moments: the glimmer of honesty with a lonely tennis player; traipsing along the U.S.-Mexico border with an organization that aids desperate migrants; a conversation with a woman who lost and gained her future by way of Skid Row — all the realities L.A. ruthlessly wishes to sweep away and pretend didn’t or don’t or won’t ever exist. When he focuses on the complexity and sheer contradictory nature of people, Baldwin succeeds. He captures these moments best when he softens his grip, almost forgetting his fixation on research and city-state, and falls into the stories just as he might walk through Koreatown, Skid Row, or Boyle Heights. I would read this book again and again just to watch that happen.

Jessica Ciccarelli is a nonfiction writer who graduated from Berea College and holds an M.F.A. from New York University. Her work has appeared in Harvard Review. She lives in Kentucky, where she is working on a memoir set in Louisiana about loss and returning home.