Fire and Hurt

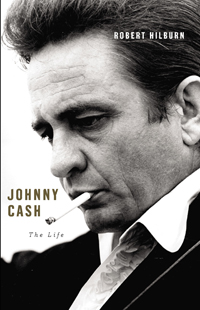

Robert Hilburn captures a music icon in his rich new biography of Johnny Cash

Ten years after his death, the popularity of Johnny Cash continues to grow. Cash’s posthumous album sales have totaled over $130 million. The 2005 film Walk the Line, which stars Joaquin Phoenix as Cash and Reese Witherspoon as June Carter, garnered five Academy Award nominations and grossed more than $300 million worldwide. From his Memphis beginnings in 1954, when he performed alongside the teenaged Elvis Presley, to his 2003 rendition of “Hurt,” recorded in Nashville months before his death and widely regarded as one of the best music videos ever filmed, Cash held unique power over audiences and those who knew him. Robert Hilburn, who spent more than thirty years as the chief music critic of The Los Angeles Times, has captured the roots of that power in Johnny Cash: The Life, a rich and thorough new biography.

This is a comprehensive book. As detailed in ample source notes, Hilburn interviewed virtually every surviving family member, producer, band member, and friend of Cash’s, creating a vivid portrait of Cash as he recorded his most memorable songs. While the book doesn’t flinch from the drug abuse and infidelity that often hobbled Cash’s creative genius, in over 600 pages it never strays far from the music, providing new insights to songs that are now an indelible part of American musical history, from “Folsom Prison Blues” and “I Walk the Line” to “Ring of Fire” and “The Man Comes Around.”

This is a comprehensive book. As detailed in ample source notes, Hilburn interviewed virtually every surviving family member, producer, band member, and friend of Cash’s, creating a vivid portrait of Cash as he recorded his most memorable songs. While the book doesn’t flinch from the drug abuse and infidelity that often hobbled Cash’s creative genius, in over 600 pages it never strays far from the music, providing new insights to songs that are now an indelible part of American musical history, from “Folsom Prison Blues” and “I Walk the Line” to “Ring of Fire” and “The Man Comes Around.”

In his acknowledgements, Hilburn explains that when he began the project he asked Lou Robin, who managed Cash for more than twenty-five years, how much of the singer’s story had been told. “Only about twenty percent,” Robin answered. Hilburn’s subsequent research uncovered a complex creative genius, a man driven by faith and a love for family but who was nonetheless often powerless against his desires for drugs, women, and his own growing legend.

As a music critic, Hilburn is at his best in discussing Cash’s creative work, but he also offers a fascinating account of Cash’s various romantic interests. Cash’s pursuit of June Carter was well-known even before the 2005 film; less often discussed were the other singers Cash was drawn to on the road. When he and Elvis, both young stars on Sam Phillips’s Sun label, toured together, Cash, whom Hilburn describes as a “happy husband and father” at the time, claimed to be disgusted by the female fans who would line up nightly outside Elvis’s dressing room. Even so, he became deeply infatuated himself with several talented female singers, especially Lorrie Collins, who was only fourteen when they first met, and Billie Jean Horton, the wife—and later widow—of Cash’s best friend, the singer Johnny Horton.

As a music critic, Hilburn is at his best in discussing Cash’s creative work, but he also offers a fascinating account of Cash’s various romantic interests. Cash’s pursuit of June Carter was well-known even before the 2005 film; less often discussed were the other singers Cash was drawn to on the road. When he and Elvis, both young stars on Sam Phillips’s Sun label, toured together, Cash, whom Hilburn describes as a “happy husband and father” at the time, claimed to be disgusted by the female fans who would line up nightly outside Elvis’s dressing room. Even so, he became deeply infatuated himself with several talented female singers, especially Lorrie Collins, who was only fourteen when they first met, and Billie Jean Horton, the wife—and later widow—of Cash’s best friend, the singer Johnny Horton.

After Johnny Horton’s death in a 1960 car crash, Cash pressured Billie Jean to marry him. “When Cash sang ‘I Walk the Line’ each night onstage,” Hilburn writes, “he was reminded of the deep conflict. He didn’t want to hurt Vivian or, especially, the girls, but he thought about Billie Jean constantly. The band members knew something was going on, but they didn’t ask.” Added to the uncertainty was Cash’s growing dependence on amphetamines, which helped him drive long hours between tour cities and also to overcome a natural shyness onstage. “Because of all the pills, we never knew from one day to the next how he would react,” one band member recalls. In the end, Billie Jean rejected his proposal, and his addiction eventually led to an arrest for smuggling pills from Mexico, but his relentless pursuit of “wild desire” became a part of his creative energy.

Cash’s career straddled what Hilburn calls “the them-versus-us nature of the Nashville-Memphis relationship,” in which Memphis represented Sun Records and the rise of rock and roll, and Nashville represented the Grand Ole Opry and the country-music establishment. Despite his roots on an Arkansas cotton-farm, where he learned to love gospel and traditional country, Cash was drawn to both folk and rock throughout his career, collaborating with artists like Bob Dylan, Kris Kristofferson, and Shel Silverstein in the 1960s, and recording songs by Nick Cave and Nine Inch Nails late in life. Eventually, he was named to both the Rock and Roll and Country Music Halls of Fame, and Hilburn masterfully depicts the line Cash walked between country and rock, showing how even within a given day, the singer would vacillate between the two worlds.

“Johnny was and is the North Star; you could guide your ship by him—the greatest of greats, then and now,” wrote Bob Dylan within hours of Cash’s death in September 2003. In Johnny Cash: The Life, Hilburn has written the greatest of any book to chronicle that star.