Flooded Hearts

Cary Holladay writes bold stories about northern Virginia’s river valleys

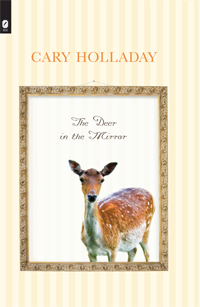

In a story from Cary Holladay’s new collection, The Deer in the Mirror, a stagecoach traveling through northern Virginia’s farms and hills suddenly bolts off the road. Amid the panic and chaos as the runaway coach hurtles toward ravines and quicksand, the passengers are thrown into a fresh state of alertness, and a pregnant young woman is jolted into labor. Standing shaky among the stagecoach wreckage, aware that he is having the adventure of his life, fifteen-year-old Lewis Mundy thinks, “This, then, is traveling. This is what it means to be out in the world.”

The stories in The Deer in the Mirror may be set mostly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but there is nothing staid or dated about them. They rollick with an energy that feels modern though never anachronistic. Set largely in Virginia’s Orange and Culpeper Counties, the stories roam mill towns, farms, riversides, and deep backwoods. Holladay, who teaches at the University of Memphis, has explored this territory in previous work, including a cycle of linked stories, Horse People, published earlier this year. Both collections benefit from the recurrence of the Virginia settings—which includes not only the land but also the region’s background characters, families who keep these communities running through many generations. This setting provides a rich context for the characters at the heart of these stories, people whose circumstances propel them into crucial moments of decision in their lives.

The stories in The Deer in the Mirror may be set mostly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but there is nothing staid or dated about them. They rollick with an energy that feels modern though never anachronistic. Set largely in Virginia’s Orange and Culpeper Counties, the stories roam mill towns, farms, riversides, and deep backwoods. Holladay, who teaches at the University of Memphis, has explored this territory in previous work, including a cycle of linked stories, Horse People, published earlier this year. Both collections benefit from the recurrence of the Virginia settings—which includes not only the land but also the region’s background characters, families who keep these communities running through many generations. This setting provides a rich context for the characters at the heart of these stories, people whose circumstances propel them into crucial moments of decision in their lives.

The men are often caught in a stirring, never truly resolvable question: which of their grand visions of themselves is the truest? Gid Ulsh, who grew up unsure of his own place after watching his father drown, reflects on the reserved nature of his adult life as vice president of the Bank of Culpeper: “Banker Ulsh is only Gid after all. This welling in his heart these days he doesn’t understand, the way the world is brighter and louder and nearer than it’s ever been, and all he can do is make his quick, polished exits. He hopes nobody sees.” Like Gid Ulsh, the other men all carry inside themselves a tension between loyalty and adventure that drives them to take action, sometimes foolishly.

The question of the women’s destinies may be even grander. These female characters are not wilting flowers: they reserve the right to make their own choices, even when the dangers and restrictions of their era threaten them. They listen to their passions, forge inventive ways of surviving, and—perhaps most compellingly—they sometimes choose to say No. Weighing a proposal from the illustrious Governor Spotswood, Verena Whitlow reflects on the pleasures of the life she has already created in her own farmhouse: “Descending the stairs, she finds a small doe in the hallway. The animal passes close enough that she runs a hand along the smooth hide. It’s an August afternoon, with the sun lighting up the river, and suddenly she feels happy and hopeful. Alexander Spotswood is in part a cause of her happiness, the more so because he is away.”

The question of the women’s destinies may be even grander. These female characters are not wilting flowers: they reserve the right to make their own choices, even when the dangers and restrictions of their era threaten them. They listen to their passions, forge inventive ways of surviving, and—perhaps most compellingly—they sometimes choose to say No. Weighing a proposal from the illustrious Governor Spotswood, Verena Whitlow reflects on the pleasures of the life she has already created in her own farmhouse: “Descending the stairs, she finds a small doe in the hallway. The animal passes close enough that she runs a hand along the smooth hide. It’s an August afternoon, with the sun lighting up the river, and suddenly she feels happy and hopeful. Alexander Spotswood is in part a cause of her happiness, the more so because he is away.”

These characters often live on the edge of respectability, not simply because of dire circumstances, but because they genuinely seem to prefer that life. By giving them a keen sense of sovereignty over their internal lives, Holladay manages to make them believable for the era but also recognizably modern. In a fascinating reversal of expectations, only the heroine of a story set in the current day—a young wife and mother named Jennilou—is struggling to overcome her internal timidity and find a voice in her own life. Placing Jennilou’s story alongside the heroines of historical fiction highlights what makes Holladay such an adept storyteller: she rejects types in favor of evoking full human beings, in all their thorny specificity.

The modern-day stories deal with the changing face of the land and the encroaching creep of development and the influence of outsiders. Of course, the historical stories, which send their characters on expeditions into untamed stretches of Virginia and as far away as the gold-rush fever of Alaska Territory, are tackling the same matters. The point is clear: even if our own age seems full of unprecedented struggle, it retains some echo of its wilder past. As older generations give way to new, even the most prominent myths and legends disperse from fading memory like mist from the Rapid Ann River. The past becomes the air we breathe.

The stories pose questions about our own choices. Will we be the kind husband and father drowned in the swollen river, or will we be the small rabbit he reached for in the fast current, somehow spared inside its wooden hutch? Will we be the white-tailed deer, trembling with its “unknowable heart,” or will we merely be the reflection of the deer, framed inside a gilt-edged mirror?

The Deer in the Mirror leaves us with the haunting suspicion that Holladay has created a kind of story-breeding ecosystem, where new and old tales of the Rapid Ann River are all the time emerging from deep hidden places, and that she periodically travels there, to scoop them up in handfuls for us. That’s how real and enduring the stories feel and how strong our hunger for more of them becomes.

Cary Holladay will discuss The Deer in the Mirror at Burke’s Book Store in Memphis on September 5, 2013, at 5:30 p.m., and at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13, 2013. Book events are free and open to the public.