Longing for Tribe

Memoirist Daisy Hernandez examines her life between worlds

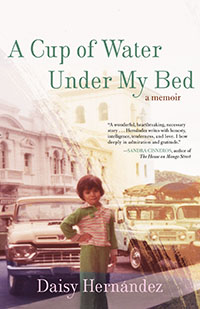

If Daisy Hernandez were running for office, her life would be likely depicted as a twenty-first-century American success story: the gifted child of poor, hardworking immigrants struggles to get an education and ultimately becomes an accomplished writer. She also discovers and claims her bisexuality, and then finds reconciliation with her disapproving family. It’s a lovely story, and true as far as it goes, but in A Cup of Water Under My Bed, Hernandez creates a richer narrative, one that reveals a more complicated, often painful reality behind the cultural cliché.

Hernandez grew up in northern New Jersey, the child of a Colombian mother and a Cuban father. Though both parents worked long hours, money was scarce. The book opens with twelve-year-old Hernandez protecting her mother, who speaks little English, from a city official’s offhand remark that their home should be condemned. There is, of course, no protection for young Daisy, who hears the official’s callous words as a blanket insult of her parents, implying that “this pot of black beans, this radio we listen to each day, these stories you tell us—he’s saying none of this matters.”

Hernandez grew up in northern New Jersey, the child of a Colombian mother and a Cuban father. Though both parents worked long hours, money was scarce. The book opens with twelve-year-old Hernandez protecting her mother, who speaks little English, from a city official’s offhand remark that their home should be condemned. There is, of course, no protection for young Daisy, who hears the official’s callous words as a blanket insult of her parents, implying that “this pot of black beans, this radio we listen to each day, these stories you tell us—he’s saying none of this matters.”

Hernandez’s mastery of English makes her, like so many children of immigrants, the family translator, but this isn’t a role she assumes easily or happily. Our stock image of the young child who effortlessly absorbs a second language and shifts easily between tongues does not apply. On the contrary, she feels compelled to abandon Spanish, even to “hate” it. The English instruction she receives in school seems like part of a wholesale cultural rejection of her parents and their world. “What is so wrong with my parents,” she wonders as a child, “that I am not to mimic their hands, their needs, not even their words?”

Her loss of Spanish is matched by a voracious acquisition of English, which in turn places increasing distance between her and her family. She remembers the whole process of assimilation as something akin to being devoured: “If white people do not get rid of you, it is because they intend to get all of you. They will only keep you if they can have your mouth, your dreams, your intentions.” But whiteness is also something she covets. Suburban white women, so happily free of ethnic identity or ties to the past, seem to possess a kind of power that fascinates her: “I envy them. I want what they have.”

There’s ambivalence in Hernandez’s attitude toward her family, as well, and it’s not entirely fueled by her own struggle with the dominant culture. Her father drinks and beats her severely enough to attract the attention of the authorities. Her mother is loving but passive, as are her beloved maternal aunts, and the whole family is burdened with a kind of fatalism that is more a product of circumstance than temperament. No one in the community of immigrants “can afford to believe in dreaming, in planning, in the pursuit of happiness,” Hernandez writes. “The good stuff in life is bestowed by God, by luck.” Religion, for better and worse, looms large in the family’s life. Catholicism, fortune-telling, and Santeria bring comfort and fear in roughly equal measure, at least for Hernandez. To her, God is a “fat white man in the sky” who doles out punishment, but she is soothed by the rituals of faith and feels empowered when her mother slides a cup of water under her bed to cure her nightmares.

There’s ambivalence in Hernandez’s attitude toward her family, as well, and it’s not entirely fueled by her own struggle with the dominant culture. Her father drinks and beats her severely enough to attract the attention of the authorities. Her mother is loving but passive, as are her beloved maternal aunts, and the whole family is burdened with a kind of fatalism that is more a product of circumstance than temperament. No one in the community of immigrants “can afford to believe in dreaming, in planning, in the pursuit of happiness,” Hernandez writes. “The good stuff in life is bestowed by God, by luck.” Religion, for better and worse, looms large in the family’s life. Catholicism, fortune-telling, and Santeria bring comfort and fear in roughly equal measure, at least for Hernandez. To her, God is a “fat white man in the sky” who doles out punishment, but she is soothed by the rituals of faith and feels empowered when her mother slides a cup of water under her bed to cure her nightmares.

This dilemma of conflicted allegiance continues into Hernandez’s adult life, as she struggles with her sexuality and tries to establish herself as a writer. A Cup of Water Under My Bed is essentially the story of a continually frustrated longing for tribe. Hernandez is both exhilarated and dismayed when she gets an internship at The New York Times and finds herself part of a white-dominated milieu that is both more powerful and less glamorous than she imagined. Her bisexuality puts her at odds with her family—one aunt simply stops speaking to her for years—but she confronts some judgment from the lesbian community, too.

There’s a deep sadness in Hernandez’s story, one that is unique to her experience of cultural dislocation yet echoes the existential sorrow we all feel about the loss of home and the imperfection of love. She suggests no remedy, but her memoir is itself an attempt to reconcile with the sorrow, and in that sense it’s a beautifully hopeful book, proof that yearning can become a kind of sustenance when it is transformed into art. Through the words she struggled with so painfully as a child, Hernandez finds redemption: “Over and over again, this truth: Writing is how I leave my family and how I take them with me.”

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.