Following the Story Wherever It Goes

After three decades in children’s books, acclaimed author-illustrator David Wiesner is still eager to innovate

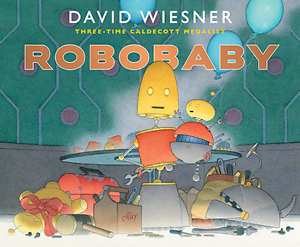

If you think making Caldecott history — being one of only two artists to win the Caldecott Medal three times, in addition to winning three Caldecott Honors — would have author-illustrator David Wiesner resting on his laurels, you’d have to think again.

During a phone conversation about his upcoming appearance at the Southern Festival of Books to discuss Robobaby, his newest picture book, he not only laughs about how lately he is described as the only living three-time Caldecott Medalist — “Thanks for starting the clock ticking there,” he jokes — but he also speaks fervently about pushing himself as an artist and trying new things.

During a phone conversation about his upcoming appearance at the Southern Festival of Books to discuss Robobaby, his newest picture book, he not only laughs about how lately he is described as the only living three-time Caldecott Medalist — “Thanks for starting the clock ticking there,” he jokes — but he also speaks fervently about pushing himself as an artist and trying new things.

Wiesner’s session at the 2020 festival will bring him full circle. His first experience at a book festival nearly 30 years ago, as a fledgling artist who had just released a book titled Tuesday, was in Nashville at the Southern Festival of Books. Shortly afterward, the book garnered Wiesner his first Caldecott Medal. Since that time, he has entertained readers with picture books both imaginative and innovative. Children’s literature scholars are even fond of characterizing Wiesner’s 2002 Caldecott Medal-winning The Three Pigs as “postmodern,” with its freewheeling disregard of picture book conventions, but it never occurred to him it would be described that way. “That’s just what we were doing in art school,” Wiesner says, “following a story wherever it would take you.”

You could say Robobaby is also postmodern, at least in its subject matter. It tells the story of a family of robots who welcome a new addition to the fold. After unpacking the new model from Robobaby, Inc., the adults run into some technical difficulties — until big sister Cathode, aka Cathy, saves the day with the correct assembly and an operating system update.

The genesis of the book came during the creation of Spot, Wiesner’s award-winning 2015 app. One of his unused drawings for the app was of a robot family. “I really liked this domestic scene of mechanical creatures,” Wiesner explains. “As time went on and I finished the app, I kept thinking about them and knew I wanted to go back to the world of paper and paint and explore that. It struck me that the robot parents would be clueless, that the technology had moved so far beyond them that, in fact, the kid they already have, like a lot of kids today, would know far more about it than the parents.”

The book took just over two years to craft. “Sometimes stories happen quickly,” he says, “and sometimes I draw and draw and follow leads and paths and, out of that, a story evolves. But the only way I can get there is to do all that drawing. And it took me just over a year to paint Robobaby. I probably haven’t painted like that since Flotsam, because the approach I took was a different kind of painting. I kind of forgot just how long it takes. And I only know one way to get the effect I’m going for, and it’s a laborious process of building layers and layers of watercolors.”

Robobaby includes some speech-balloon dialogue, à la the world of comics, but fans of Wiesner’s work know that he’s a master of wordless tales, including Flotsam (2007 Caldecott Medal winner). He’s been researching wordless picture books for years now and finds it “absolutely fascinating.” With worded picture books, he explains, “the text drives the experience. When wordless books are used, that’s taken away.” Research has shown that there is an increase in the number of words used when interacting with a wordless picture book. “Books without words, in fact, inspire more words and dialogue between parent and child,” Wiesner adds. “Kids have more ability to express themselves.”

Robobaby includes some speech-balloon dialogue, à la the world of comics, but fans of Wiesner’s work know that he’s a master of wordless tales, including Flotsam (2007 Caldecott Medal winner). He’s been researching wordless picture books for years now and finds it “absolutely fascinating.” With worded picture books, he explains, “the text drives the experience. When wordless books are used, that’s taken away.” Research has shown that there is an increase in the number of words used when interacting with a wordless picture book. “Books without words, in fact, inspire more words and dialogue between parent and child,” Wiesner adds. “Kids have more ability to express themselves.”

Along with trying his hand at an app, Wiesner also collaborated with author Donna Jo Napoli in 2017 on Fish Girl, a graphic novel. “That was in my phase of ‘let’s shake things up’ and ‘let’s do some different things,’” he said. “I love picture books, and I’m not going to stop doing picture books,” he adds, but he also loves working in new forms. As someone who loved comics as a child, he was thrilled to work with Napoli. “Comics and graphic novels have come so far so quickly — much more than I would have expected. It’s very exciting.”

Wiesner’s work as an adjunct faculty member at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts reinforces his belief that story is paramount — whether it’s a tale of airborne frogs, postmodern pigs, or flummoxed robots. “It’s all story based,” he says. “It’s really all about how to tell stories with pictures. I ask my students, ‘What is personal to you?’”

To emphasize his conviction that artists should embrace what excites them and do “what nobody else is going to do,” he tells the story of seeing the Surrealists as an older elementary student and the effect it had. “After seeing Dali and Magritte, all my drawings changed. And when I came into the field, it never occurred to me not to draw on that, and it’s served me well. Because it’s personal, as opposed to wondering if I can fit myself into the market. It is what is unique about the things that I’ve experienced and seen. To me, that’s the thing that will set your work apart.”

[David Wiesner’s visual essay about the creative process behind Robobaby can be found at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.]

Julie Danielson, co-author of Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews, BookPage, and The Horn Book. She lives in Murfreesboro and blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.