Food Fighter

Fast Food Nation author Eric Schlosser brings a message of hope to Nashville

In the late 1990s, when investigative journalist Eric Schlosser began researching Fast Food Nation, his revealing and deeply unsettling look at the ills of America’s fast-food industry, few major mainstream supermarket chains had whole sections devoted to organic goods or carried antibiotic-free meat—both fairly commonplace today. Fewer still were the fast-food joints offering healthy options like carrots and fruit cups.

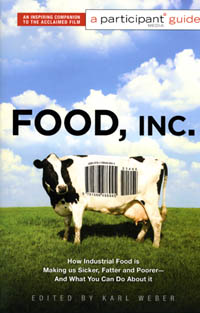

In the intervening decade, healthy eating in America has entered a new era, though much about the food industry remains in dire need of overhaul. Last year, in the Oscar-nominated documentary Food, Inc., Schlosser—a co-producer and expert voice for the film—again gave Americans the gut-churning details we need to start making wiser, warier choices about food and to push for critical change in federal policy. His assiduously researched call to consciousness about what we eat, and how we come by what we eat in the age of industrialized agriculture, has been a driving force behind many Americans’ evolving attitudes about food. It’s no exaggeration to suggest that this work has positioned him as something of an Upton Sinclair for modern times. Before his February 15 talk at Belmont University, Schlosser set aside time to talk with Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: Fifty years from now, how do you think we’ll be talking about the current industrial food system—factory farming, big agribusiness, and the like?

Chapter 16: Fifty years from now, how do you think we’ll be talking about the current industrial food system—factory farming, big agribusiness, and the like?

Schlosser: I don’t think it will have totally vanished, but I think we’ll look back and say, I can’t believe people would eat that. The amount of damage it’s doing not just to the environment but to people’s health, is something you can’t sustain for generation after generation. The health implications of this diet are going to push changes in production. Assuming that there isn’t a total financial breakdown in this country, I think what we’ll see is that the sort of changes that are being enjoyed by the well-educated upper classes right now will extend throughout the rest of society. The current system, to me, morality and ethics aside, just seems completely unsustainable. We’ll see, but I’d love to be right.

Chapter 16: The rate at which consumers’ tastes and demands are changing to embrace organic and locally grown food, to seek out humanely raised and prepared sources of meat and dairy, seems pretty astonishing.

Schlosser: Things are changing enormously quickly. When I first started researching Fast Food Nation in the late ’90s, so many of these subjects were not being debated or discussed. There’s been a sea change in the decade or so since. I’m not taking credit for it by any means; I simply feel like I can measure it because I know how things were when I got involved versus today. Then there’s the sheer interest in food: Celebrity chefs, continual bestsellers about food. I don’t personally care that much about food in that way. I’m not really a gourmet; I’m not interested in taste-testing olive oil. For me, food is an important bellwether of the culture, a way of looking at much bigger issues in society and the economy at large. You look at the history of the civil-rights movement, or the environmental movement, or the abolitionist movement—these things take time. If you use those sorts of measures, it’s amazing how quickly this movement around food, and social justice around food, has arisen. And how quickly more change could come in another ten years, knock on wood. I think it’ll be incredible.

Chapter 16: It seems to me that this change is in rapid motion above a certain income level, as people make the decision to spend a little more, to go out of their way to choose the healthier, more ethical options. But would you say that more needs to happen at a systemic level for the benefits to reach other Americans? Can the first type of change beget the second?

Schlosser: Yeah, I think part of it is systemic and part of it is access to information. So much of the current system depends on ignorance, on disinformation and misinformation. Once people see how the system works and have the financial means to eat differently, they do. So much of the problem now is connected to class and income. The huge changes I’ve seen in the last ten years are by and large enjoyed by the upper-middle class and the middle class. The real junk food is the food of the poor in the U.S., and of ordinary working people, particularly in hard economic times.

Right now there’s a real shortage of democracy if you look at how the special interests control the federal government. Just as a small example: The National School Lunch Program (NSLP), which is taxpayer funded, has basically been operated for years as a subsidy for the meatpacking companies. USA Today recently did a great investigative series about how the chicken being served to children in the NSLP was inferior to the chicken that KFC was buying. That’s able to continue as long as it’s hidden. But since it was brought to light, the USDA has started making changes.

What I hope will happen is that there’ll be a major push regarding what we feed children in schools, how we educate children not just about nutrition but about fitness, and how we allow companies to market to small children. That, in and of itself, could make a big change in the system.

Chapter 16: In Food, Inc., Joel Salatin, an organic farmer, says he never wants to sell his meat and produce at Wal-Mart, while Gary Hirshberg, the CEO of Stonyfield Farms, argues that getting his products in there is the only real way to change our food system. What do you think?

Chapter 16: In Food, Inc., Joel Salatin, an organic farmer, says he never wants to sell his meat and produce at Wal-Mart, while Gary Hirshberg, the CEO of Stonyfield Farms, argues that getting his products in there is the only real way to change our food system. What do you think?

Schlosser: Wal-Mart is so powerful that if they want to do something for sustainability it can have a huge impact immediately, which can be good. But I just don’t know that in a democracy one corporation should have that much power over an entire market. I think good anti-trust enforcement would help enormously. In the last twenty years, we’ve lost sense of how capitalism requires real competition if it’s going to exist. So I would probably err more on Joel Salatin’s side. I like Gary a lot, I think he’s sincere and is doing good things, but I think corporations should be a lot smaller, and that applies to food producers, supermarkets, banks, etc. Monsanto is a perfect example: The idea that any one company should control 90 percent of one of the two or three biggest food commodities we produce, in this case soybeans, and that Monsanto also controls sixty or seventy percent of our corn—that’s just ridiculous. It’s wrong from a democratic point of view, and I also think it’s wrong from an efficiency point of view.

Chapter 16: To challenge factory farming, it seems, means to challenge the goal of efficiency. Can a more responsible food production model also be efficient?

Schlosser: The question you have to ask is: efficient for whom? Before we had an environmental movement, chemical companies could literally take their waste chemicals and dump them in a river. If fishers downstream lost all their catch, and the people who drank the water were poisoned, well, it didn’t matter to the [chemical companies]; those were costs they were externalizing on the rest of society.

So when I say efficiency, I mean for all of us. Factory farming is incredibly inefficient when you factor in public health and environmental costs. If you have a business, you want to be able to operate that business long-term, and these companies are showing that they can’t operate long-term just because of the damage that they’re already inflicting. The costs of the obesity epidemic in the U.S. are now higher than the annual revenue of the fast food industry, or approaching it. So these companies are imposing enormous costs on the rest of society, and that’s a hugely inefficient system. And one of the big aims is going to create incentives in the system so that companies who do the right thing are rewarded and companies who do the wrong thing pay the price.

Chapter 16: What businesses make your “gold star” list of companies that are making an effort to do things in better ways?

Schlosser: It’s hard to find the perfect company. Costco has had some pretty good food safety rules in place for a while. It also pays good wages to its workers and has decent benefits, compared to Wal-Mart. I think Whole Foods is very concerned about these issues. People criticize it because in certain markets it can hurt independent health food stores that have been there for a long time, but Whole Foods has also brought sustainably produced foods to areas that really haven’t been served before. Chipotle is trying to source its foods more sustainably. (My teenage son is largely composed of Chipotle.) I’ve disagreed with them about some of their purchasing policies, but I think they’re sincerely trying to do things a different way with a different set of values. But there’s not one blanket approval for any company. Ideally, you shop locally; you shop from people you know; you buy at farmers’ markets; you do the best you can.

Chapter 16: It seems much harder to convince people to care about workers’ rights than to care about food safety that might hurt their children. How do we work to affect change on that issue?

Schlosser: If the meatpacking workers who are being injured and the farm workers who are being exploited had blond hair and blue eyes, we would never tolerate it in this society for a minute. There is an element of racism. I feel incredibly fortunate that my work has brought me into those worlds because it’s given me a sense of how we are so connected to the people at the bottom of society, whether we want to admit it or not. But outside of high-minded self-interest—outside of compassion, of justice— caring for what happens to the workers, ultimately, in the most selfish way, is going to make it better for you as a consumer. It all comes back around. A lot of the same things that lead to the high injury rate in our slaughterhouses are the things that lead to the contamination of the meat. The line goes too quickly, the meat gets contaminated because fecal matter gets spread on the meat because they’re running too fast.

Chapter 16: You’ve done a lot to raise awareness of the ills of industrialized food production. Where will you take your inquiry next?

Schlosser: As an activist who speaks out and tries to make change, I’m definitely going to stay with food issues. I really care a lot about food safety and worker safety and childhood obesity. But as a writer, this is it pretty much it for me. The film in a lot of ways marks the end of my creative involvement with these issues. I’ve been working on two books simultaneously: one about prisons in America, and another on an even cheerier subject, which is nuclear weapons. These all sound like the most depressing things imaginable, but I think my own optimism is what allows me to write about these very dark subjects. These things are dark, but it doesn’t have to be this way. That’s a lot of what my work is about: showing people that there’s nothing inevitable about the way things are.

Chapter 16: Food, Inc. starts with you ordering a burger, saying it’s your favorite meal. After all the research you’ve done on the problems in our food industry, what are your eating habits like?

Schlosser: I start with the presumption of imperfection and then I try to do my best. When it comes to the shopping that we do for our household, we try to buy organic, and I never buy meat produced from the industrial meat system. But if someone invites me over for dinner I don’t interrogate them about where the food came from. I think that once you’re aware of these issues, sometimes there’s this weight, the feeling that you have to be perfect in avoiding this system, and I feel like that mentality can, first, be overwhelming, and, secondly, lead to a feeling of helplessness or inaction. But in my mind, if enough people make just a few changes, we can really make a big difference in the overall system. I do think that to strive for purity can lead to madness. It’s impossible to be perfect and pure in the year 2010. Maybe there is someone who is, and I don’t know that I want to meet them, because it’d just be too irritating.

Chapter 16: What will you be discussing during your talk at Belmont University?

Schlosser: I’m going to talk about sustainability in terms of yourself, your family, and your community. A lot of times it’s about what we are doing to the land. I’m going to try to talk about it in terms of what are we doing to ourselves and our culture. I’m just trying to get people to see how they’re connected to other people. If you are from a nice, white, upper-middle class family, eating well and doing Pilates, that’s great—but the fact that one out of every two African American children born in the year 2000 is going to develop diabetes, according to the CDC—that is going to affect your life.

Eric Schlosser will speak at Belmont Heights Baptist Church at Belmont University on Feb. 15 at 7 p.m. The event is free and open to the public.