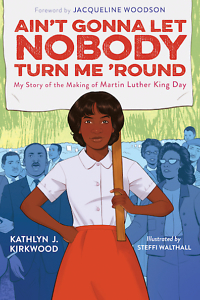

Foot Soldier for Justice

Kathlyn J. Kirkwood discusses her memoir for young readers on the making of MLK Day

“I was just seventeen,” writes Kathlyn J. Kirkwood in the opening lines of Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round, “a senior at Booker T. Washington High / in Memphis, Tennessee.” It is 1968 as she steps down Beale Street with her school’s marching band in a celebration kept separate from the “Whites only” Cotton Carnival. “Ugly things were happening in America,” Kirkwood adds, “especially in the Deep South.”

This middle-grade memoir in verse, with illustrations by Steffi Walthall and a foreword by author Jacqueline Woodson, brings to vivid life Kirkwood’s memories of her growing civic awareness and activism as a teenager. It began with her participation in the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike that same year: “With each step,” Kirkwood writes, “I grew prouder and / more confident.” Soon, a riot breaks out (“I thought that I was going to die”) and, not long after that, the news came that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot in Kirkwood’s own hometown.

Into her adult years Kirkwood continued marching and protesting for racial justice. Devastated by King’s death, she participated in the decades-long struggle to turn his birthday into a national holiday, all captured in this compelling, deeply felt memoir.

Kirkwood, born and raised in Memphis, is a retired college professor and now focuses on writing and volunteering with disadvantaged elementary students in the Nashville area. Chapter 16 talked with her via email about her debut children’s book.

Chapter 16: You touch upon this in your book’s closing acknowledgments, but can you talk about your road to publication, which you describe on your website as “anything but linear”?

Kathlyn J. Kirkwood: Yes! I have always felt the call to write and publish, and I have many manuscripts in various stages of completion. For a long time, writing was placed on the back burner because, well, life happens, as we all well know. It wasn’t until I was in my 60s that I finally leaned into writing and began making it a priority.

This book, in particular, ran into some of the same hurdles. It originally started as an oral presentation called “How Dr. King’s Day Came to Be,” which I was presenting to young adults and teens at workshops and seminars. The idea of turning that into a book was actually at the suggestion of one of my church members, Jeanne Arradondo. From there, it still took time for me to focus on this book; I was working on another manuscript at the time. And then — because this book is part autobiography, part historical narrative — there was a lot of necessary research to ensure I had the facts surrounding the legislative history correct. Once I had secured a publishing deal, I worked with the editorial staff to make sure we were presenting a really great product.

And so that is how, at age 70, I find myself with a debut book — via a very crooked road.

Chapter 16: What does it mean to you to have your debut children’s book published by Versify, Kwame Alexander’s relatively new imprint?

Kirkwood: It means a lot to me, especially because Kwame is one of my favorite authors and I admire him not only as an author, but also as an activist in his own right. I thought my book would fit well at Versify, an imprint that focuses on changing the world for the better through the written word.

Chapter 16: Your descriptions about what it was like to participate in this activism as a teenager are detailed and compelling. Do you remember your teenage years vividly? How did you go about reconstructing those memories and putting them to paper?

Kirkwood: Yes, I absolutely remember many impactful moments of my teen years — marching band, my first heartbreak, etc. Obviously, some memories had faded with time and some I had simply forgotten. For those, I had countless conversations with my siblings and several of my high school friends, whom I call my Gem sisters — you can see them in the book!

Chapter 16: The book’s epigraph is a quote from Reverend Joseph Lowery about not letting “anybody turn back the clock on our journey for justice,” and one of your verses ends with a direct question to readers: “America, do you hear us now?” Are you hoping this book will inspire the middle-grade readers at whom it’s aimed to get engaged in their own activism for racial equity in present-day America?

Yes, I want them to pick up the activism banner and get busy changing the world. But no, because that banner does not have to solely focus on racial equity. There are innumerable causes, crises, and issues confronting America and the world, and I wouldn’t want to limit anyone’s activism to only racial equity, although work is still needed on that front.

My hope is that my young audience will be inspired by my story to act on their passion, whatever that may be, as long as they are thinking about the world at large and working to make it a better place for all its inhabitants.

Chapter 16: Can you talk about the literacy work you do with your husband, Alan? How do you think the workshops you’ve developed for third- and fourth-grade students in Nashville inform your writing?

Kirkwood: With pleasure. What’s now known as Team Kirkwood Literacy Lab has evolved over the past eight years. It began with me visiting a friend’s fourth-grade class to seek help in developing a manuscript about bullying. I enjoyed it so much that I asked if my husband and I could visit the class on a regular basis. When we first started, we engaged with second, third, and fourth grades only until an invitation to present and “bring books to life” to a sixth grade class was offered. On the website I call it “Literacy Remix IV” because of the many different grades we work with.

Literacy is our new passion. We work with disadvantaged children, some homeless, to bring light and hope where many times it appears there is none. Our literacy program involves more than coming into a classroom to read. We bring books to life by drawing out themes and having the children discuss them, and we also present interactive, sensory experiences based on the books. For example, we introduced Demi’s One Grain of Rice, and at its conclusion the students sampled brown, white, yellow, and black rice. We also read Sandra Neil Wallace’s Between the Lines: How Ernie Barnes Went from the Football Field to the Art Gallery, illustrated by Bryan Collier, and we brought in a local artist to speak to the students about being a painter.

The Literacy Lab presentations we do help me think about how teachers would bring my book to life. This is why I included pictures of the petitions and the infographic of how a bill becomes law — to name a few additions to my memoir — so that teachers and educators can create an interactive experience when reading and discussing Ain’t Gonna.

Chapter 16: You write about not even realizing until age 28 that you were poor as a child, because you lived in a bubble of “merriment and self-made fantasy” and your parents shielded you from the “separate and very unequal ideology of segregation and Jim Crow.” When you work with middle-grade students today, how do you balance this need to extend their innocence with the realities of racial injustices in America today? How do you handle those kinds of discussions with them if they come up?

Kirkwood: As a I stated, we work with disadvantaged youth who are mature beyond their years. Some have witnessed drive-by shootings, some are homeless, and some have to miss school to help care for younger siblings. So I do not shield truth and reality, but I make sure that what I teach is age-appropriate. If anything, with this group I’m conscious of making sure that our interactive experiences always have an element of fun for them. Ultimately, my goal is to paint a picture of the world that will inspire passion and birth lifelong activists.

Julie Danielson, co-author of Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews, BookPage, and The Horn Book. She lives in Murfreesboro and blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.