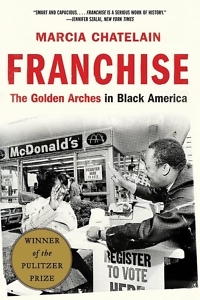

Freedom and Fries

Marcia Chatelain explains how McDonald’s intersects with the history of the civil rights movement

Every year, the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change at the University of Memphis bestows an award for the nonfiction book, originally published in the previous year, that best furthers understanding of the American civil rights movement and its legacy. The 2020 winner is Marcia Chatelain’s Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, a brilliant examination of the fraught relationship between the McDonald’s restaurant chain and the Black freedom struggle.

Chatelain is professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University. The author of South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration, she writes widely on topics such as race, education, and food culture. Franchise has also won the Hagley Prize in Business History, the Lawrence W. Levine Award from the Organization of American Historians, and the Pulitzer Prize in History.

Marcia Chatelain answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: How did you come to write about McDonald’s? When did you see this subject as a viable topic for a historian of race in America? As you researched and wrote, how did the project evolve?

Marcia Chatelain: As a historian, I’m always looking for a common reference point to bring readers to the table of learning. I’m always looking for a familiar object or a comfortable lens with which I can help people understand the nuance of the past. McDonald’s is the perfect topic, because many people have experiences of it and opinions about it, but few people understand how this fast food restaurant relates to a broader history. I knew that McDonald’s could provide the perfect entry point for civil rights history after I first learned that McDonald’s recruited Black franchise owners soon after Martin Luther King Jr.’s death. Initially, I was going to write a book about food and civil rights broadly, but I realized that a really deep history emanated from McDonald’s, and it was worthy of its own investigation. Once I decided to focus on McDonald’s, I found a treasure trove of stories.

Chapter 16: On one of Martin Luther King’s visits to Memphis in 1968, he asked, “What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t have enough money to buy a hamburger?” What was King’s vision for economic empowerment? How did his assassination shape the McDonald’s story?

Chatelain: For King, economic justice and racial justice were intertwined, and within his final oration, he spells out the importance of boycotts and the great economic power that rested among Black communities. This vision of economic justice included organized labor, a federal government that took the plight of the poor seriously, and a critique of capitalism. His message was lost in the reactions to his death that centered on Black economic empowerment through the opening of businesses and the elevation of Black capitalism. After King’s assassination, a number of entities tried to respond to the so-called urban crisis and to King’s death by promoting the opening of Black businesses, and there was a sense that inclusion in corporate structures could remedy racial discord and despair.

Chapter 16: President Richard Nixon touted “Black capitalism” as a remedy for African American poverty in the wake of the civil rights movement. How did McDonald’s franchises show the possibilities and limits of this idea?

Chatelain: Fast food franchising provided a tangible and financially lucrative example of success. These restaurants epitomized all the promises of capitalism in mid-century America: the myth that anyone could be a success in business, the popular culture of cars and fast food, and the idea of consumer citizenship. The fundamental problem of fast food as a vehicle for economic empowerment is that the opportunity is limited to the people at the very top. Workers were not able to access the fortunes of the industry. The menu does not provide a sustainable source of food for communities. And, at the end of the day, fast food cannot save neighborhoods and communities, regardless of who is in the position of power or leadership.

Chatelain: Fast food franchising provided a tangible and financially lucrative example of success. These restaurants epitomized all the promises of capitalism in mid-century America: the myth that anyone could be a success in business, the popular culture of cars and fast food, and the idea of consumer citizenship. The fundamental problem of fast food as a vehicle for economic empowerment is that the opportunity is limited to the people at the very top. Workers were not able to access the fortunes of the industry. The menu does not provide a sustainable source of food for communities. And, at the end of the day, fast food cannot save neighborhoods and communities, regardless of who is in the position of power or leadership.

Chapter 16: Franchise profiles a number of African Americans who owned McDonald’s franchises. How did they see themselves and their roles in Black communities?

Chatelain: The Black franchise owner was, and remains, part of the long history of Black businesspeople providing unelected leadership, philanthropy, and jobs to the local communities. The early Black franchisees were among an emerging group of Black professionals who were able to leverage their proximity to Black communities to gain influence and share resources. Today, Black franchisees continue to maintain important connections to their consumer base. One of the reasons why McDonald’s is so important to Black patrons is because segregation in living and spending brings franchisees close to the people they serve.

Chapter 16: In modern assessments of poor urban areas, fast food restaurants such as McDonald’s often attract blame for exacerbating health problems by serving fatty foods, as well as for offering only low-paying dead-end service jobs. Can a historical perspective help to reshape this landscape?

Chatelain: I think that these facts are true, but there is so much more. The history of McDonald’s in Black America is also a cautionary tale about investing in private business rather than public resources. It is a way to understand America after 1968. It’s the source of complicated and complex relationships between diners and restaurants, communities and spaces, and politics and activism. I hope that this history makes people more sensitive in the ways they talk about individual choices and more likely to challenge institutions.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.