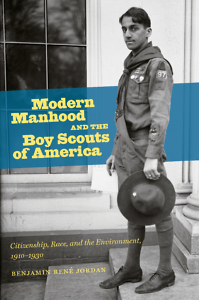

From Boys to Men

Benjamin René Jordan describes how the Boy Scouts helped to define modern manhood

In Modern Manhood and the Boy Scouts of America: Citizenship, Race, and the Environment, 1910-1930, Benjamin René Jordan recounts a moment in American history when the modern corporation became the dominant model for civic life, shaping mainstream ideas of manhood. In Jordan’s persuasive reading, the Boy Scouts of America “articulated and widely promulgated a new male norm,” one which combined Victorian moral virtues like modesty and diligence with modern corporate values of efficiency and loyalty, putting them into practice in a structured approach to the natural world. In other words, the Boy Scouts of American inculcated the traits “that white males needed to maintain control of an increasingly urban and corporate-industrial society.” Jordan’s thorough, well-researched history of the BSA has insights for the contemporary reader.

The organization had all of the hallmarks of a modern corporation from the start: a rigid, top-down system of management, with a massive bureaucratic paper trail as a result—Modern Manhood is so thorough partly because the BSA kept such detailed records and survey data. Jordan gives a solid picture of the goings-on from the top down and the bottom up, from elite organizers in boardrooms to the everyday experiences of scouts.

The organization had all of the hallmarks of a modern corporation from the start: a rigid, top-down system of management, with a massive bureaucratic paper trail as a result—Modern Manhood is so thorough partly because the BSA kept such detailed records and survey data. Jordan gives a solid picture of the goings-on from the top down and the bottom up, from elite organizers in boardrooms to the everyday experiences of scouts.

Because today’s multinational corporations act rather like nation-states unto themselves, it would be easy to read the sources in this book backward from the present, seeing the beginnings of something almost sinister in the mission of the BSA—one in which Progressive reformers and intellectuals like the psychologist G. Stanley Hall or Theodore Roosevelt made common cause with corporate titans like John D. Rockefeller Jr. Reformers and capitalists alike saw the massive coordination of capital and human beings in vast bureaucracies as part of a seemingly inevitable historical process. It was not only pointless but downright atavistic to reject it. The Boy Scouts of America, its founders believed, could ease the transition into this new world by making boys into responsible corporate citizens, the embodiment of “full-orbed manhood.”

This goal meant doing away with older, quasi-Emersonian notions of nature as a source for spiritual insights. Boys went to nature to learn how to compete in a corporate, cooperative setting. Adapting to the scout camp Frederick Winslow Taylor’s ideas about labor by the stopwatch was a stunning example. The “Pine Tree Patrol Method” for instance, “provided numerous drills with exact diagrams to teach differentiated tasks to eight boys in a Patrol to achieve the greatest group and time efficiency in setting up and striking down a complete Scout Patrol camping layout,” Jordan writes. “Scouting brought an ethos of industrial efficiency and strict time management into nature itself.”

The second part of the book concerns those who fit uneasily into this modern, corporate vision. The organization sought a non-sectarian, broadly inclusive membership—with certain limits. The BSA had a much easier time integrating Southern and Eastern-European immigrant boys into its ranks than it did African Americans, for example. That they tried at all is remarkable for the time. Still, their printed materials sometimes indulged in Jim Crow stereotypes of laziness and segregated African-American troops with second-class membership.

The BSA also failed spectacularly to bring rural scouts into its ranks, and Jordan’s account of this failure reveals some critical tensions at the heart of his story. Because the BSA demanded conformity to its essential goals and organizational structure, a more flexible parallel group called the Lone Scouts popped up to cater to the needs of rural boys. Lone Scouts completed advancement requirements free from adult supervision or managerial oversight. Though the BSA eventually absorbed the group, it refused to compromise, turning a deaf ear to the voices of its country constituents. It lost countless members, though their loss doesn’t appear to have mattered much. The takeover of the Lone Scouts was about corporate branding: because the BSA had been granted a legislative charter, enjoying “semi-public” status, its leadership demanded exclusive use the use of the word “scout” for its marketing and merchandising. (The BSA tried unsuccessfully to put the Girl Scouts out of business for the same reason.)

The BSA also failed spectacularly to bring rural scouts into its ranks, and Jordan’s account of this failure reveals some critical tensions at the heart of his story. Because the BSA demanded conformity to its essential goals and organizational structure, a more flexible parallel group called the Lone Scouts popped up to cater to the needs of rural boys. Lone Scouts completed advancement requirements free from adult supervision or managerial oversight. Though the BSA eventually absorbed the group, it refused to compromise, turning a deaf ear to the voices of its country constituents. It lost countless members, though their loss doesn’t appear to have mattered much. The takeover of the Lone Scouts was about corporate branding: because the BSA had been granted a legislative charter, enjoying “semi-public” status, its leadership demanded exclusive use the use of the word “scout” for its marketing and merchandising. (The BSA tried unsuccessfully to put the Girl Scouts out of business for the same reason.)

Executive leaders also refused to make any provision for working-class scouts who couldn’t afford the cost of uniforms or dues. Doing so, they argued, would create separate classes of boys, which the “classless” vision of the BSA wouldn’t allow. Though Jordan doesn’t make this argument, we know now that refusing to compromise on a point of cost because of a “classless” ideal is how hegemony works, masking indifference to human struggle with the rhetoric of “inclusiveness.” (To be fair, the BSA did back off on the uniform requirement during the Great Depression.)

On the whole, Modern Manhood and the Boy Scouts of America is an accomplished account of the complicated ideas of training for civic virtue in a modern, corporate setting. It should be essential reading for those who want to understand how the world of a century ago continues to influence our own.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses having to do with American culture and writes scholarly articles about American political thought and the civil-rights movement.