Fugitive Truth

Oxford American editor Roger D. Hodge discusses his vision for the magazine’s future, the role editors play in storytelling, and the depth of his own ties to the South

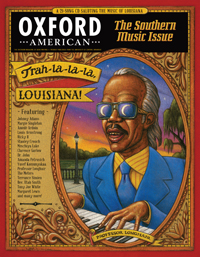

Former Harper’s Magazine editor Roger D. Hodge took the reins as editor-in-chief of the Oxford American at a precarious moment in the magazine’s twenty-year history. Founding editor Marc Smirnoff had made an abrupt, much-publicized exit just as OA’s biggest issue of the year—the annual music issue—was fast approaching. The magazine needed a seasoned editor, preferably one with Southern ties and a clear understanding of the journal’s mission. Hodge was an ideal match: a West Texas native who graduated from the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, before building his career at Harper’s, where he was editor-in-chief from 2006 to 2010.

Hodge, who is also author of The Mendacity of Hope: Presidential Power, Corporate Money, and the Politics of Corrupt Influence (Harper, 2010), has praised the Oxford American’s unique history and vision, calling it a “great American magazine.” Answering questions from Chapter 16 via email, he addresses a range of topics, including his role in shaping OA’s future:

Chapter 16: You stepped in to edit Harper’s Magazine after Lewis H. Lapham’s departure; now you’re following founding editor Marc Smirnoff at the Oxford American. How does following a longtime editor, one who has left his signature on the magazine, affect your approach to the job?

Chapter 16: You stepped in to edit Harper’s Magazine after Lewis H. Lapham’s departure; now you’re following founding editor Marc Smirnoff at the Oxford American. How does following a longtime editor, one who has left his signature on the magazine, affect your approach to the job?

Roger Hodge: Very few editors enjoy the luxury of founding a new magazine, so almost every magazine editor must contend in one way or another with the practices of his or her immediate predecessor. There’s nothing unusual about that. All editors leave a mark, and every new editor enters into a conversation with the traditions of the publication he or she inherits. Out of that interaction something new results.

Chapter 16: For years, the Oxford American has been known for what Smirnoff called “truthful glimpses” into the South. Now that you’ve been on the job for a few months, how would you describe your own vision for OA’s future?

Hodge: “Truthful glimpses” is a nice phrase. All writing involves a courtship with the truth. But truth is a fugitive, an elusive target that changes shape as time passes and illuminating expressions and metaphors harden into opaque clichés.

There’s a wonderful piece in our fall issue by Harold Hayes, the great editor of Esquire magazine. It’s an excerpt from an unpublished manuscript, from a chapter entitled “The Editor’s Implied Control.” Hayes, a strong editor with a singular vision, is eloquent about the limits of an editor’s ability to shape a magazine. The ultimate limit of that control is really the writer.

Writers tell stories. The editor’s job is to help them tell their stories in the best possible way. That’s it.

My ambition for the Oxford American is that it should be a showcase for writers, not editors. I’m not the kind of editor who likes to come up with a big idea for an issue and then recruit writers to fill in the blanks. That’s a perfectly valid approach to what some editors like to call “magazine making,” but it’s not what I do. My approach to editing is more conversational. I am in touch with a small army of writers who are spread out all over the country, gathering up characters and dramas and happenings of all kinds. After they’ve worked over that material and baked in their own obsessions and preoccupations, stories emerge. I listen to the stories, and I pick and choose the ones that are most compelling. My colleagues and I then compose a context for the stories, arranging them so that they complement one another. When everything comes together in just the right way, so that the stories are winking and glancing across the issue at one another, something magical happens. You have a self-contained whole, a world within the world. That’s the art of editing as I understand it. Writers tell stories. The editor’s job is to help them tell their stories in the best possible way. That’s it.

Chapter 16: You’ve mentioned your interest in featuring long-form journalism at the magazine. Are there particular writers you’re courting for those assignments? It’s not hard to imagine fellow Sewanee alum John Jeremiah Sullivan in that role.

Hodge: Nowadays it often seems that everyone is talking about “long form,” especially on Twitter, which seems slightly ironic to me, and there are some who have begun to roll their eyes at this buzzword. After all, most good editors try to make their stories as short as possible. Sometimes length is merely self-indulgence, and often it’s much harder to run a piece at 6,000 words than at 10,000 words.

Hodge: Nowadays it often seems that everyone is talking about “long form,” especially on Twitter, which seems slightly ironic to me, and there are some who have begun to roll their eyes at this buzzword. After all, most good editors try to make their stories as short as possible. Sometimes length is merely self-indulgence, and often it’s much harder to run a piece at 6,000 words than at 10,000 words.

Though I share the discomfort some veteran editors have with the term, I think the vogue for long-form journalism is welcome. I hope it lasts. Sites like Longform.org perform a welcome service to readers and publishers alike. Curiously, though, many of the pieces that appear on the aggregation websites devoted to long-form journalism seem pretty short to those of us who grew up reading The New Yorker under William Shawn, William Whitworth’s Atlantic, or Lewis Lapham’s Harper’s.

My preferred term for what we do is literary journalism, but whether you call it long form, literary journalism, narrative nonfiction, creative nonfiction, or the lyric essay, we’re really just telling stories. The OA has always been in the storytelling business, and we’ll continue to publish the best writing that we can put our hands on, both nonfiction and fiction, so in that sense I don’t think my editorial approach will constitute a radical departure. My sensibility and my tastes differ in important ways from my predecessor’s, but that’s to be expected. The balance of inquiry may shift slightly from personal introspection toward the outside world, but such storytelling need not be long. My aim is always to find the natural length of a piece. Some stories demand great length; others work better at fifteen hundred words.

As for John Sullivan, he is my brother in arms. I suspect you’ll be seeing him in our pages very soon.

Chapter 16: As a publication dedicated to writers with connections to Tennessee, we’re interested in your years as an undergraduate at the University of the South. Looking back, do you see any specific ways Sewanee helped to shape you as a writer or editor?

Hodge: I was something of a bomb thrower as an undergraduate, but even in the midst of my post-adolescent ersatz-punk rebellion I had enough sense to realize that Sewanee was a good place to learn how to write. I immersed myself in Southern literature. Henry Arnold’s Faulkner seminar was a real turning point in my education. In many ways my entire adult life, both professional and otherwise, has been shaped by my decision to attend Sewanee. I met my wife there, and it was there that I first learned of Harper’s Magazine. My teacher Tom Spaccarelli introduced me to Jack Hitt, who was an editor at Harper’s, and Jack encouraged me to go to New York and try to work there. That encounter propelled me into my career at Harper’s. And it was at Sewanee that I first encountered the writings of Cormac McCarthy, who like my great-great-great grandfather followed the Western road from Tennessee to Texas. McCarthy’s influence on my approach to writing has been immense.

I was something of a bomb thrower as an undergraduate, but even in the midst of my post-adolescent ersatz-punk rebellion I had enough sense to realize that Sewanee was a good place to learn how to write.

Chapter 16: You’re telecommuting right now from your home in Brooklyn. Given that this magazine has always been deeply rooted in the specificity of the South’s people and places, is the fact that it’s now being edited from New York in any way emblematic of the nature of the South—or perhaps of the media—in the twenty-first century?

Hodge: I don’t think so. I believe the center of creative gravity in the United States is moving away from the traditional media centers on the East and West Coast. The fact that I’m still living in New York results from my professional history and the fact that I have an artist in my family who would never forgive me if I tore him away from what’s probably the best arts-oriented high school in the country. My wife has a job she loves, and she is in no great hurry to pick up and move. Even so, we certainly never expected to live in New York City for twenty-two years. Chances are that we will eventually move south.

Editors tend to spend much of their time in dim rooms filled with bright screens, or in well-lit rooms filled with books, and that is true whether they live in Flatbush, Brooklyn, or Conway, Arkansas. I’m very grateful that technology now makes it so easy to collaborate over long distances. On the other hand, I do travel frequently—to Texas on reporting trips, and to Arkansas and other points south on magazine business—so I don’t think my engagement with the varied landscapes and cultures of the South suffers from my continued exile in the northeast.

Chapter 16: Your book, The Mendacity of Hope, sharply criticizes President Obama for failing to meet expectations from progressives and for appropriating certain elements of the Bush-era war on terror. Any predictions for Obama’s second term?

I believe the center of creative gravity in the United States is moving away from the traditional media centers on the East and West Coast.

Hodge: I wouldn’t say that Obama failed to meet my expectations. The president’s various betrayals and shortcomings were fully predictable and they were in fact predicted, and not only by me, long before he was elected. I suspect that we’ll see more of the same. The Mendacity of Hope was primarily an argument about political corruption. What I tried to show in my book was that most politicians—even relatively eloquent and attractive politicians like Barack Obama—in our system are best understood as investment vehicles for rent-seeking business enterprises. We spend far too much time in American public life parsing the characters of the hollow men who pretend to lead us. Far better, in my view, to bracket the questions of personality and intention and focus on something objective, like the return on investment for political contributions and lobbying.

Chapter 16: You’re working on a new book about your native stomping grounds, the West Texas borderlands. What can you tell us about the book?

Hodge: The book is a literary investigation of life in West Texas, which was a borderland long before the United States existed as such. Formally it is a braided narrative that takes my family’s history in the ranching business over the last 150 years as one of its strands. In some ways the book is an elegy for the dying ranch culture in which I was raised. Not much is left of it now. Most of the land in my home county has been emptied of the cattle, sheep, and goats that once grazed along the Pecos and the Devils River. Near Juno, where my family still ranches, there are fences along the highway that have been down for years. The landowners aren’t running livestock, so why should they care if the fences are down?

The ranchers were only one of a long parade of cultures that has tried and mostly failed to create lifeworlds in that harsh country. In their place have come the frackers, the wind farmers, and the border industrial complex. Law enforcement is now the dominant industry. Although the border country seems remote, this is not an isolated phenomenon. Indeed, the border and what the border represents—permanent, pervasive, and persistent surveillance—appears to be expanding to fill the entire country.