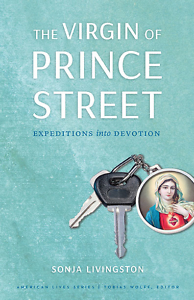

Full of Grace

Sonja Livingston recounts her search for a missing Virgin Mary statue and her own mislaid faith

In the opening pages of The Virgin of Prince Street, Sonja Livingston describes how, after a vigil at her in-laws’ Presbyterian church, she made a last-minute detour to hear Mass at Corpus Christi, the Catholic church she’d loved as a girl. “The simple elegance of the [Presbyterian] service had been a good match for my head,” she writes, “but the tangled mess of my heart longed for something else.” This collection of essays, with an interwoven detective story, describes where that knotty longing carried Livingston, a writer who, nearing middle age, felt something missing in her good life and “returned to a church pew as if it were an old love.”

Like most old loves, the object of Livingston’s childhood affections was not as she remembered it. Although the stalwart old sandstone edifice at the corner of Main and Prince still stood, gone were the folk-music Masses and social-justice leanings of a church so “unusually progressive” that it allowed altar girls long before the Vatican did. Decades on, demographic shifts in Rochester and other Rust Belt cities had caused many parish churches to close and consolidate as their congregations shrank. Corpus Christi mercifully remained, but Livingston noticed the changes even there: emptier pews, unfamiliar faces, and a collection of refugee statuary from disused churches. But most unsettling to her was the disappearance of her favorite statue of Mary, draped in a sky-blue cloak.

Thus begins the detective story at the center of this book: Livingston’s search for her beloved Virgin of Prince Street, a mission that takes her all over Rochester, to icy Buffalo in midwinter and, by her own admission, beyond the bounds of reason. She weaves together stories of dogged statue sleuthing with gorgeous meditations on faith and explorations of sacred rituals far and wide, from a grotto in Ireland to a mobile confessional in Louisiana. In chronicling the varied ways people seek divinity, she homes in on the notion that reason isn’t always the most important thing.

It took half a lifetime to arrive at that notion, but the seeds were always there. Livingston had herself been an altar girl, although, she admits, not a particularly pious one. Born to a single mother of seven, Livingston’s unpredictable early life had endowed her with a pragmatism that left her feeling that “faith was a luxury … for girls with picture-perfect families.” But an even deeper skepticism emanated from her disappointment with religious language itself, how applying words to limitless concepts like divinity, salvation, and miracles seemed to shrink them. She recalls her frustration as she challenged fellow parishioners about the biological impossibility of virgin birth:

No one admitted doubt. No one suggested different ways of knowing or contemplation of words like faith and skepticism — or even virginity itself. Instead they clung to the story’s literal hinges … How alone I suddenly felt. Bad enough to be a kid from the family that got food baskets every Christmas — now it seemed I was the only one at Corpus Christi who adored the Blessed Mother whether her virginity was figurative or not.

No one admitted doubt. No one suggested different ways of knowing or contemplation of words like faith and skepticism — or even virginity itself. Instead they clung to the story’s literal hinges … How alone I suddenly felt. Bad enough to be a kid from the family that got food baskets every Christmas — now it seemed I was the only one at Corpus Christi who adored the Blessed Mother whether her virginity was figurative or not.

Maybe it’s her acceptance of the contradictions inherent in faith, and in the Church itself, that paved the way for Livingston’s return. She’s at home in the presence of the complicated and the unknowable and with the bewildering blend of heart and mind that religious belief entails.

For Livingston, devotion doesn’t require black-and-white thinking or rigid categorization. Her Church is rife with both abuses and riches but still worthy of her fealty. And her search for the blue-cloaked Virgin of her memory was never about idealizing or restoring the past; it was to help Livingston understand that the flaws are no barrier to faith. “Devotion,” she writes, “is less about where it’s bestowed than the disposition of the one who does the bestowing.”

I won’t ruin the mystery by telling you whether the author finds her Mary of Prince Street. What matters more is that she searched the world and found Mary everywhere. “I’d see her in museums and chapels and garden grottoes and feel the air flicker between us,” she writes. That Marian omnipresence — or really, the fact that Livingstone let herself be attuned to it — revealed that her childhood connection to the Virgin had never been severed, even in the author’s years away: “[I]t’s possible I loved her all along and it took the shock of her absence to remind me how much.”

Kim Green is a Nashville writer and public radio producer, a licensed pilot and flight instructor, and the editor of PursuitMag, a magazine for private investigators.