Fusion Food

Writer John T. Edge has made a career of chronicling the place where food and culture come together

Once upon a time, when the humble strip of bacon had yet to become a culinary fetish object; when mac and cheese was simply a side item on the meat-and-three menu, and not a concept for modish urban restaurants, a young man named John T. Edge roamed the back roads of the American South in search of good, authentic meals. He found them in no small number, and he also found his calling.

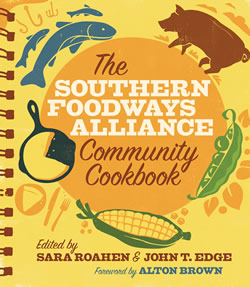

Edge’s story marks a stirring new chapter in the culture of Southern food. As a devoted chronicler of the people and places of Southern cooking, and as director of the Southern Foodways Alliance at the University of Mississippi, Edge has helped to inspire a renaissance in Southern food—its celebration and documentation, its public perception, its dreams for the future. Over the years, the SFA has produced an extensive bank of oral histories and short films and a popular film-festival series; it has sponsored internships, scholarships, field trips, fundraising dinners, and an annual symposium (next year’s topic: The Cultivated South); and in 2010, the organization compiled The Southern Foodways Alliance Community Cookbook. The creators envisioned it as “an old spiral-bound cookbook of the sort that was popular before the Junior League thought it would make a mint on coffee table style books,” as the SFA website explains.

While helping build the SFA, Edge has also established a reputation as one of the most sought-after food writers in the country. In the pages of magazines such as the Oxford American, Gourmet, and Garden & Gun, he has brought the stories of the people, places, and ingredients of Southern food to enthusiastic eaters and readers. Of course, he’s not the first to take up the cause: he himself is quick to credit the influence and work of his mentor, Nashville-based writer John Egerton, whose 1993 book, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History, is a literary touchstone for the SFA’s mission and a sort of primer for anyone hungry to read, or write, about the culinary South.

Carrying on that tradition, Edge has sopped up a stew of accolades, including five nominations for the James Beard Foundation Award and appearances in seven editions of Da Capo Press’s annual Best Food Writing anthology. For Edge, a Georgia native, food has been a portal to exploring the frequently misunderstood and misrepresented cultures of the region he has always called home. In his book Southern Belly: The Ultimate Food Lover’s Companion to the South (Hill Street Press, 2000), he explains, “I have an appetite for the lore that defines life in the Southern United States. … If I did my job well, this book should read like a social history of Southern food,… a mosaic-like portrait of the South as told through its foods, a pastiche of people and places that sates both mind and belly.” But he has also has taken his journey above and beyond the Mason-Dixon, first in a series of books exploring “iconic American eats”—hamburgers and fries, donuts, apple pie, and fried chicken—and, since 2009, via “United Tastes,” a column in The New York Times through which he delivers engaging and surprising food narratives, among them the tale of the signature cashew chicken dish of Springfield, Missouri; the path of the microplane from hardware store to kitchen drawer; and turkey smoking in Tyler, Texas.

Carrying on that tradition, Edge has sopped up a stew of accolades, including five nominations for the James Beard Foundation Award and appearances in seven editions of Da Capo Press’s annual Best Food Writing anthology. For Edge, a Georgia native, food has been a portal to exploring the frequently misunderstood and misrepresented cultures of the region he has always called home. In his book Southern Belly: The Ultimate Food Lover’s Companion to the South (Hill Street Press, 2000), he explains, “I have an appetite for the lore that defines life in the Southern United States. … If I did my job well, this book should read like a social history of Southern food,… a mosaic-like portrait of the South as told through its foods, a pastiche of people and places that sates both mind and belly.” But he has also has taken his journey above and beyond the Mason-Dixon, first in a series of books exploring “iconic American eats”—hamburgers and fries, donuts, apple pie, and fried chicken—and, since 2009, via “United Tastes,” a column in The New York Times through which he delivers engaging and surprising food narratives, among them the tale of the signature cashew chicken dish of Springfield, Missouri; the path of the microplane from hardware store to kitchen drawer; and turkey smoking in Tyler, Texas.

Chapter 16 caught up with Edge while he was—as he so often is—on the road, driving from his home in Oxford, Mississippi, to Macon, Georgia. This weekend, he’ll moderate the shrimp and grits cook-off at Savor Nashville. (“If you’ve ever heard John speak,” writes Chris Chamberlain on Bites, the Nashville Scene’s food blog, “you know that he is as smooth as molasses sliding off the edge of a buttered biscuit, and I’m certain that he’ll be a very entertaining host.”)

Chapter 16: Your work must keep you on the road a lot. Is the New York Times column going to continue for the foreseeable future?

Edge: I certainly hope so. It’s a very good gig. I’m deeply invested in the South, but my interest in food culture isn’t restricted to this region. The column allows me to look at the ongoing evolution of American culinary culture, and it allows me to look at what’s happening in this moment. That’s a real gift.

Chapter 16: So what is going on in food at this moment?

Edge: What’s most interesting to me is the honest fusion that’s ongoing in American culinary culture. I did a piece not too long ago about teriyaki in Seattle. When you think about Seattle, teriyaki is not the totemic food that comes to mind. You think about the great access to Pacific coast seafood, or, if you’re a lover of salumi, you think about Mario Batali’s father who makes great salumi there. But if you look closely in Seattle, you realize that the city is chockablock with teriyaki shops in strip malls, in retrofitted fast-food bunkers, in downtown storefronts. I went to a Somali-owned restaurant frequented by cab drivers, and they were serving a riff on teriyaki. In these shops, they’re serving teriyaki burritos, corndog teriyaki. To me, Seattle is a teriyaki town.

So, by looking at what people really eat, not what we as Americans want to tell you we eat, not what we as boosters want to show you we eat, but by looking at what we really eat and looking at some foods that people might dismiss—like bastardized teriyaki—I think you can make sense of what’s going on in America right now, which is that honest fusion of cultures. I find that endlessly fascinating.

Chapter 16: And it’s beautifully, quintessentially American for people to take a given culture’s dish and remake it their own ways—and for that to be going on beneath the radar, in the most pedestrian places. I love that story about cashew chicken in Springfield, Missouri, for example.

Edge: Oh, thanks. That was the very first one in the series. If you think about it, cashew chicken is the food that best represents Springfield, with its Midwestern/Southern farm roots, of which fried chicken is an emblematic dish, and with immigration that brings new people to that place. The food tells the story of entrepreneurship in America—and of our intolerance to new arrivals at times as well, and our eventual acceptance of them. You can see that whole American arc in a story about fried chicken smothered in brown gravy with cashews scattered on top.

Chapter 16: The food is an entry point to telling that story.

Edge: Yeah. If I’m being really egotistical and full of myself, I think of what I’m doing as writing about race and class and gender and ethnicity, but just using food as a way of doing it. Now, I love to eat, and I think food culture is really important, but I’m not that interested in vacuous fetishism and celebration of expensive and exclusive foods. That’s boring. And it doesn’t yield much. It’s an exercise in “Look at me, look at what I’m eating, aren’t I cool.” To me, what is interesting is to write about food that’s relatively unheralded and people that are relatively unheralded. To turn a camera or a mic on them and listen to their stories. That’s a responsibility and it’s also, for me, a real joy.

Edge: Yeah. If I’m being really egotistical and full of myself, I think of what I’m doing as writing about race and class and gender and ethnicity, but just using food as a way of doing it. Now, I love to eat, and I think food culture is really important, but I’m not that interested in vacuous fetishism and celebration of expensive and exclusive foods. That’s boring. And it doesn’t yield much. It’s an exercise in “Look at me, look at what I’m eating, aren’t I cool.” To me, what is interesting is to write about food that’s relatively unheralded and people that are relatively unheralded. To turn a camera or a mic on them and listen to their stories. That’s a responsibility and it’s also, for me, a real joy.

Chapter 16: Now that you’ve expanded your reach to the rest of the U.S., do you feel like the South merits an organization like the SFA in a way that other regions don’t?

Edge: No, the South is not the soul redoubt of regional food culture; it’s rich and diverse. There is a Midwestern Foodways Alliance that we consulted on; there’s Sabores Sin Fronteras (Flavors Without Borders), based in Tucson; and there’s Foodways Texas based out of Austin. I think Southerners, for reasons of race and class, may have looked more closely at their food culture at an earlier stage in the development of the region than other parts of the country, but I think once you look closely at those other parts of the country, they yield comparable stories of comparable depth.

Chapter 16: What are your proudest moments so far with the SFA?

Edge: At this point, I’m a mouthpiece, a fundraiser, and a guy with a Rolodex in his head for the connections that people in the South can make. I’m proudest of the oral history and film work that my colleagues have done. My colleague Amy Evans Streeter has interviewed over 500 people across the South and collected their oral histories—the story of their life in food, but also just flat-out the story of their life. In terms of paying homage to the unsung farmers and cooks and artisans of the South, Amy has set national standards. Everyone who does this sort of work follows in her wake. I’m really proud of what she’s done. The same thing applies to SFA filmmaker Joe York. This is a day when anybody with a camera can make a film, but I would challenge anybody with a camera who can make a film to take a look at what Joe does, and take a look at the themes he coaxes out, sometimes with a great deal of humor and sometimes with a great deal of seriousness.

The other thing that matters about the work of the SFA is the community that now claims the organization, a group of people who see food as a portal to understanding people and place and who see food from the South as a kind of lever-point for a better South, not in the political sense, but in a community-building, awareness-raising sense.

Chapter 16: So when you’re in Nashville this weekend, are there places you want to hit for lunch or dinner?

Edge: I’m hoping to get to town in time for lunch at Arnold’s Country Kitchen, and I hope that we can swing by Prince’s for some chicken as well. We have nieces and nephews in Nashville, and a few years back when given the charge of bringing some food to a christening shower, where everybody wears white, I made the mistake of bringing some of Prince’s hot chicken. I haven’t heard the end of that, with good reason.

There are a ton of restaurants in Nashville that I really like. My wife and I are having a date-night on Friday; we’re going to City House. The SFA held one of our Potlikker Film Festivals there a couple years back, so I want to introduce my wife to the place. And we’re staying at the Hermitage Hotel. My son really likes nice hotels, so he’ll be pumped about that. We’ll go to Capitol Grille for brunch on Sunday.

Chapter 16: So you’ll get a little food culture on both ends of the spectrum.

Edge: Yeah, that to me is what’s interesting. You need balance in your life. The balance between Arnold’s and City House, between Prince’s and Capitol Grille, that’s the way I like to eat and to live. I think there’s a connectivity between working-class restaurants and white-tablecloth restaurants. The work that I try to do is connecting those two worlds in people’s minds. And I learned that lesson, the import of that, from a Nashville guy, John Egerton. He’s been my mentor in this world of food, and so much of his work has inspired mine. Working-class cooks of the South were the backbone of his book Southern Food. And they’re the backbone of all of our restaurant food experiences. I want to make sure that in this moment when everyone’s celebrating Southern food, that we’re not solely focused on the high-profile chef, but that we’re focused on the fry cook with an apron strapped around his waist.

Chapter 16: What about the argument that Southern food is unhealthy?

Edge: I get asked this question so much, and it really gets under my skin. In the case of outlanders, I think it speaks to a disrespect for the South that’s tied up in a whole lot of stereotypes and misinformation about the South. On the part of native Southerners and people who claim the region, I think there’s an insecurity to the question, that says the things we produce are not worthy, or are lesser. I don’t eat fried chicken every day. I eat it maybe once every couple of weeks. Once every couple of weeks is not a detriment to my health. Two nights ago, we had fresh turnip greens, pulled from a garden down the road from our house, stir-fried in olive oil with a little garlic. That’s good for you!

Chapter 16: You’ve made the observation that Southern food may have a marketing problem. That makes a lot of sense to me.

Edge: I think Southern food prepared badly is just like any other food prepared badly—awash in grease, prepared from canned food, goosed in sugar: no, it’s not good. But think about the meat-and-three: it’s three vegetables and one meat. It’s not three meats and one vegetable. It’s a vegetable-centric cuisine. And maybe I was being a little hyperbolic in my response, but I think that to dismiss Southern food as unhealthy is to look the other way when a parade of Midwesterners goes by with their tenderloin sandwiches in hand. And it’s to look the other way when Californians go by with a sack of In-and-Out burgers.

There are many reasons to question the South, and our long and ugly legacy of race relations is one, but I think of our food as one of the biracial creations, along with music, as one of the great folk symbols of the South’s perseverance and creativity that should be celebrated. Yeah, there’s bad stuff out there. But I don’t think we should take a wide swipe at Southern food and dismiss it. And I don’t think we Southerners should take up that same mantle and accept the chip on our shoulders. There are smarter ways to think about Southern food.

Chapter 16: You’re working on a book about food trucks. What spurred you to write about that?

Edge: I got interested in it, fortunately, before the trend really took off, in part because I traveled to Vietnam about five years ago and fell hard for street food in Vietnam. And I’m interested in truck food for its democratic roots. Six or eight years ago, I traveled through L.A. and saw how omnipresent taco trucks were out there. They weren’t the place [where] immigrants ate; they were the place everyone ate.

There was a trend back in the 90s and early 2000s where there were these chef’s tables, where you’d have an opportunity to sit in the kitchen and the chef would cook food and hand it right to you. That was something you’d pay extra for, it was valued. What is truck food but that? I think that’s one of the reasons that people connect with truck food so much. You stand in line, you look the cook in the eye, and you tell them what you want. They cook it and they hand it to you. People crave the intimacy of that interaction.

Chapter 16: I like that interpretation. There’s also the way that food trucks as a trend have dovetailed with social networking. There’s a game, almost, in figuring out where the various trucks are going to be today, where you might be able to catch one.

Edge: Yeah, we’re talking about two complementary phenomena. There’s the new, hipster brand of food trucks, and then there are the taco trucks up and down Nolensville road, which were there long before Twitter was invented. There’s a complement there, but long after the hipster trend ebbs and the really successful trucks become brick-and-mortar restaurants, which so many of them have a tendency to do, the working-class food trucks are going to keep going. Because somebody who’s got five minutes to eat and wants something better than the crud McDonald’s shovels out the window is going to go to that taco truck.

Chapter 16: Speaking of trends: during the time you’ve made your name as a food writer, the term “foodie” has become a commonplace. What do you think of that?

Edge: As you might expect in asking me that question, I detest that term! I think it’s dismissive of the farmer who tills the soil and raises the crop that the consumer values. Calling consumers foodies is like calling them junkies. It’s like saying they can’t help themselves, like their appreciation of food is somehow a psychosis. It implies a vapidness on the part of the person who is interested in food. It sounds fey and pompous; it fails in its descriptive intent. But I don’t know what to replace it with. I’ve failed at that.

There’s something about the worshipfulness of a “foodie” that bothers me: the gossip-mongering about chefs as if they are beatific entities to whom we should bow down. Most people I know who work in food don’t want that kind of worshipful approach and don’t warrant it, either. They’re just mortals with saucepans.

Chapter 16: Do you ever get tired of writing about food?

Edge: No, I love what I do, and I love that I get to do it. I ‘m kind of stunned by what I get to do. I’m not bailing out any time soon.

Chapter 16: I read on Twitter that you were just in Louisiana, where you were going to “catch, kill, [and] cook cochon de lait,” which is a Cajun roast pig. What was that like?

Edge: Well, that was a little overwrought, but I was out with Joe York, who I mentioned earlier, and he’s working on a film that will debut at the Big Apple BBQ Block Party in New York on June 12, about cochon de lait as cooked in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. So I was out there to tote Joe’s bag when he needed it and drive the car and support him in some small way.

I thought I knew a lot about barbecue and roasting pigs, but I’ve never seen anything like they do in Avoyelles Parish. They sandwich the small pig in a wire net, suspend it nose down over or in front of a pecan wood fire, and then crank up a small motor that keeps the pig twirling in front of that fire. The fire is backed by a reflective piece of metal, so that the smoke and the heat buffets the pig. I’ve never seen a pig done that way, and it proves to me that no matter how much you travel and no matter how much information you compile about regional foodways, there’s always something new and something interesting, some kind of compelling story down the road or around the corner.

John T. Edge will moderate the shrimp-and-grits cookoff at Savor Nashville on June 5 from 2 to 4 p.m. at the Hutton Hotel. Order tickets here.