Gardening with George (and John, and Thomas, and James)

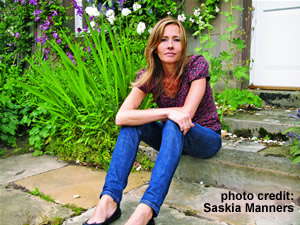

In Founding Gardeners, Andrea Wulf gets to the roots of America’s beginning

Writer and gardening historian Andrea Wulf makes a bold claim in the opening of her new book, Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation. After describing how a visit to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello motivated her to learn more about the botanical habits of that august group known as the founding fathers, she states, “[I]t’s impossible to understand the making of America without looking at the founding fathers as farmers and gardeners.” While historians may debate her thesis, it is certain that Wulf has wonderfully illuminated an often overlooked and very important aspect of the founders’ lives, providing new reasons to be inspired by them.

George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison are the stars of Founding Gardeners, and it’s hard to imagine four more influential members of the revolutionary generation. Ben Franklin and Alexander Hamilton make appearances in the book, but the first four presidents provide more than enough examples of how early American leaders intertwined their politics with their passion for the land. All preferred the beauty of their gardens to the pressures of serving the nation. Washington was so happy to leave the military for the pleasures of planting trees at Mount Vernon that it was difficult for his countrymen to lure him back to the nation’s service as president. Yet even in gardening, the man who had risked everything fighting for liberty couldn’t resist making political statements. Following a trend that began in Britain, Washington designed his beds and groves for philosophical effect, knowing, Wulf says, that “the gardens in front of his house would be an expression of his vision of republican simplicity, and his personal statement of independence.”

Adams, the only one of the four to hail from a state other than Virginia—and therefore the only one who did his farming without exploiting slaves—is the founder least associated in the public’s mind with agriculture. Yet Wulf, whose previous foray into gardening lore, The Brother Gardeners, also chronicled eighteenth-century botany, has proven that even the often forgotten second president was amazingly well versed in the science, art, and technology of the garden. He was, for instance, zealously interested in the use of dung as a plant nutrient, studying it even while serving abroad as the American Minister to the Court of St. James. “One of the most charming images from Adams’s life,” Wulf writes, “was his close investigation of a manure heap just outside London.” In other words, one of America’s leading politicians was up to his elbows in what the Republican Party of the day accused him of dishing out during his presidency.

Adams, the only one of the four to hail from a state other than Virginia—and therefore the only one who did his farming without exploiting slaves—is the founder least associated in the public’s mind with agriculture. Yet Wulf, whose previous foray into gardening lore, The Brother Gardeners, also chronicled eighteenth-century botany, has proven that even the often forgotten second president was amazingly well versed in the science, art, and technology of the garden. He was, for instance, zealously interested in the use of dung as a plant nutrient, studying it even while serving abroad as the American Minister to the Court of St. James. “One of the most charming images from Adams’s life,” Wulf writes, “was his close investigation of a manure heap just outside London.” In other words, one of America’s leading politicians was up to his elbows in what the Republican Party of the day accused him of dishing out during his presidency.

Jefferson is, of course, often remembered as a scientist as much as a politician, so his appearance in Founding Gardeners was required. Even with one of America’s most researched and recorded heroes, however, Wulf has dug out new and interesting nuggets. Jefferson constantly collected seeds and plants, corresponding with anyone, including political foes, who could provide the latest and greatest specimens and intelligence. During his time as secretary of state in the Washington administration, he was particularly enamored with sugar maples. In 1791 he visited New England with Madison, a trip famous in American history for its effects on the founding of political parties. But throughout the journey, Jefferson avidly investigated the maple, both as an object of scientific interest and as a tool against British—and, in Jefferson’s mind, Federalist—economic tyranny. As Wulf notes, “It was as if the formations of orderly rows upon rows of upright saplings were symbols of America’s defiance against Britain, an arboreal army fighting for economic independence.”

There are portions of Founding Gardeners that seem to fall short of proving Wulf’s argument that understanding the true origins of this nation requires seeing the founders as men of the soil. But even these passages provide delightful, enlightening reading. How many modern Americans know that several of the most important delegates to the Constitutional Convention , including Madison and Hamilton, relieved the tensions of the debates by taking a field trip to a nursery where they could share their thoughts on plants? And Wulf’s chapter describing the construction of Washington, D.C., is not only a meditation on the perils of expressing politics in municipal design but a comedy in which a “group of congressmen got so lost one evening that they had to spend the rest of the night zigzagging through bogs and wasteland in search of Capitol Hill.” Take that, John Boehner and Harry Reid.

In this day of hyperpartisan divides, it is often difficult to believe that men of competing, even mean-spirited, politics once found common ground in the appreciation of nature and the practice of agriculture. Belief in the virtues of farming and husbandry of the land was remarkably bipartisan, with both Federalists and Republicans convinced that the growth of the nation was, if not dependent on, certainly reflective of the growth of their vegetables, grains, and flowers. “The well-tended fields of small farms,” Wulf writes, “became a symbol of America’s future as an agrarian republic.” The ideal image of the virtuous farmer tending his crops persists to this day, even as an urban landscape has replaced a rural one as the center of American life.

In this day of hyperpartisan divides, it is often difficult to believe that men of competing, even mean-spirited, politics once found common ground in the appreciation of nature and the practice of agriculture. Belief in the virtues of farming and husbandry of the land was remarkably bipartisan, with both Federalists and Republicans convinced that the growth of the nation was, if not dependent on, certainly reflective of the growth of their vegetables, grains, and flowers. “The well-tended fields of small farms,” Wulf writes, “became a symbol of America’s future as an agrarian republic.” The ideal image of the virtuous farmer tending his crops persists to this day, even as an urban landscape has replaced a rural one as the center of American life.

Their tremendous interest in the cultivation of plants, Wulf argues, made the founding fathers the first American environmentalists. A fine example is a remarkable speech James Madison gave in May of 1819. The former president and Father of the Constitution traveled from his beloved Montpelier not to speak expressly about politics or the formative events in the nation’s history. He appeared before the Agricultural Society of Albemarle to present a synthesis of philosophy, soil chemistry, and biology that he had conceived during his years as a planter and amateur botanist. The audience heard what can only be described as an exhortation to be conservationists, to preserve the land for future generations. It was an extraordinary idea for so young and vast a nation, but it was a speech, Wulf writes, “that would make him one of the most respected farmers in America and would place him at the vanguard of forest and soil conservation, decades before a concerted effort was made to preserve America’s nature.” In becoming a voice for preservation of the resources of the nation he helped create, Madison was working to ensure that his and his colleagues’ efforts at political gardening would yield nourishing fruit for generations to come.

As part of the Salon@615 series, Andrea Wulf will discuss and sign Founding Gardeners in the Nashville Public Library’s courtyard at noon on April 20.