Ghosts and Strangers

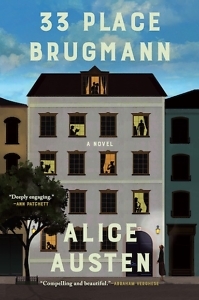

A Brussels building becomes a refuge from the inhumanity of war In Alice Austen’s 33 Place Brugmann

For a story set amid the darkness and ugliness of World War II, Alice Austen’s 33 Place Brugmann is peculiarly focused on beauty. Set largely in the eponymous Brussels apartment building, this debut novel depicts the struggles of a group of characters for whom art and life are interchangeable. Mere survival doesn’t suffice; they cling to the hope that, when the ravages of war subside, the jewels of civilization will be restored to their pedestals. One character supports this notion by quoting Wittgenstein that “ethics and aesthetics are one and the same.”

The novel itself testifies to the truth of this claim. Austen rotates the narration among the building’s residents, each providing a unique perspective that contributes to the overall mosaic. The structure of the interlocking stories resembles a parquet floor, like the one Francois Sauvin, an architect, installs in the living room of his apartment. The aesthetically pleasing parquet comes to symbolize the manifold ways that residents rely on one another to preserve what’s most valuable.

While some of the characters are forced to leave the building — starting with Jewish art dealer Leo Raphael and his family, who wisely escape to the U.K. before the Germans march into Belgium — the hub of the novel remains in Brussels. Francois’ daughter Charlotte, an art student, becomes the emotional center of these interconnected lives.

Charlotte’s color blindness provides Austen with an effective metaphor to account for variations in perception. Rather than a range of hues, Charlotte sees the world in gradations and textures. “While she may not see pigments, she sees subtle differences between them,” her father explains. “Charlotte has a more discerning ability to see what is commonly called color than the rest of us.” Seeing the world in “gray scale” contributes to her emotional “counterpoise,” enabling her to be calm in explosive circumstances.

Masha Balyayeva, a Russian Jewish refugee who lives in the fifth-floor garret, sees Charlotte as “only light”: “To me, she was an angel.” Austen includes some demons, too; her cast represents the full ethical spectrum, from the morally ambivalent to the utterly depraved. Some Belgians welcome the Nazi occupation as an opportunity to improve their social stations; humble merchants become ruthless profiteers. The Flemish citizens, who have for generations controlled the Belgian bureaucracy, aid the Nazis by identifying every person of Jewish ancestry. As one character points out, “We don’t need Germans to have villains, see, we have plenty on our own.”

Though evil surrounds Place Brugmann, Austen devotes most of her tale to the defenders of goodness and beauty. The Raphael family, none of them saints, doesn’t allow the tsunami of European antisemitism to destroy their spirits. The daughter Esther becomes a nurse, not to glorify God or preserve the species but simply as an expression of her natural instincts. Her brother Julian, who precedes his family to England as a student at Cambridge, suspends his study of mathematics to enlist in the RAF. Leo devotes himself to the preservation of art, while his wife Sophia clings to her belief that kindness defines humanity: “Doing things for people even when they’re doing nothing for you.”

Though evil surrounds Place Brugmann, Austen devotes most of her tale to the defenders of goodness and beauty. The Raphael family, none of them saints, doesn’t allow the tsunami of European antisemitism to destroy their spirits. The daughter Esther becomes a nurse, not to glorify God or preserve the species but simply as an expression of her natural instincts. Her brother Julian, who precedes his family to England as a student at Cambridge, suspends his study of mathematics to enlist in the RAF. Leo devotes himself to the preservation of art, while his wife Sophia clings to her belief that kindness defines humanity: “Doing things for people even when they’re doing nothing for you.”

Characters often find that doing right is complicated, especially when one’s actions can have fatal repercussions for others. Masha follows her lover to Paris and gets drawn into the Resistance, joining a network that helps smuggle British soldiers out of occupied territories. What she discovers is that human motivations can’t be divided into simple, black/white categories. Instead, like Charlotte’s vision, “there are infinite shades between.”

33 Place Brugmann covers three eventful years, from 1939, when rumors spread about the coming German invasion, to 1942, when the Allies start to weaken the Nazis’ hold on Europe. Before optimism can return, Austen’s characters fear that their entire world may be destroyed. Francois Sauvin tries to lift the morale of Colonel Warlemont, a World War I veteran who lives in the next apartment, by sharing home-brewed beer, but he can’t help observing the stark changes in his old friend: “I never thought I’d live to see the Colonel waste away,” Sauvin says. “Maybe the Colonel has been replaced by an imposter. But I know I look different too. We’re all being replaced with ghosts and strangers.”

For all the trials these characters endure, the novel celebrates human resilience, the capacity for life-affirming action despite death’s shadow being cast on every home, even the “fortress” of 33 Place Brugmann. Some residents scurry for safety, but others, following Charlotte’s example, learn the beauty of risking oneself to protect others. Readers who enjoyed Amor Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow will find a similar sensibility at work here: an accidental crew of misfits, thrown together by the horrors of war, finding a camaraderie that makes life worth protecting.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.