Giving Hope a Trellis

In Edgar Kunz’s Fixer, plain language makes way for depth of meaning

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on October 4, 2023.

***

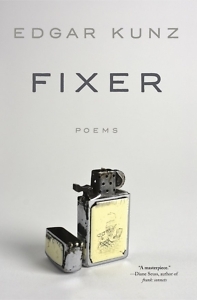

“Zippo with a carving of a whale, / proud ship in the distance.” Zippo. A common, and even to some, vulgar image, reimagined as a small symbol of warmth, grief, and complicated fatherhood. This is the lyrical alchemy that we encounter in Edgar Kunz’s latest collection of poetry, Fixer.

Kunz, who received an M.F.A. from Vanderbilt, is also author of Tap Out, named a New & Noteworthy book by the New York Times in 2019. The Times described Tap Out as a collection that surveys the “physical terrain of blue-collar masculinity,” and Fixer focuses on a similar milieu.

The narrative arc of Fixer bends toward an American simplicity, winding through scenes laden with the accoutrements of working-class life. He writes, “It’s weeks before you’re entered / into the system, more weeks / to get your tiny check.” He explores the novel, working-class experience of creating plushness in poverty, “My sweetheart and I have / a rented apartment the size / of half a train car, / but we have a miniature / dishwasher, so we feel / we live in luxury.” But the arc returns, like memories, to the journey of brothers sorting through the effects of their deceased father. Kunz first introduces this tension in the poem “Day Moon” with a type of simple poetic brushstroke: “another / unsober voicemail from my dad.” Then, in “Squatters,” we return to this storyline: “Mom calls. Are you alone, she says. / It’s about your dad.”

The news leads us into the titular poem, “Fixer.” The first sections of the poem are addressed to the speaker’s father, “We’re breaking into your apartment / through your bedroom window” and “Better than the minivan you slept / a winter in, American Legion / parking lot, siphoning gas for heat, / but not much better.” The immediate effect of this perspective shift is to pull the reader into the speaker’s grief. We are also sons in sorrow. And not only are we drawn into the sadness, but also into the beggarly elements of the father’s apartment. We are breaking in. There is, then, in the lines that follow, a silent we.

Kunz writes without the collective pronoun, but the reader’s ear has already been turned: “[We] Got in / through the window. [We] Waded through / the cans and bedding. [We] Left it open / for the smell.” A lyrically shrewd move. We find ourselves wondering at the small growing points of sorrow in our own chests. Right then, Kunz repositions the poetic lens again and we see the father through the eyes of the speaker’s younger brother, Noah. This tertiary filter, the speaker remembering his brother remembering his father, brings an anomalous but advantageous viewpoint to the text. We discover that maybe “Fixer” is the speaker’s way of saying “father”: “plus he [the father] could fix / anything, he was amazing, leaky faucet, / done sticky door, done, lawn mower / won’t start, done.” But perhaps the speaker, the son, experiences his own transformational shift into a type of fixer by fixing or settling the affairs of his father.

Kunz writes without the collective pronoun, but the reader’s ear has already been turned: “[We] Got in / through the window. [We] Waded through / the cans and bedding. [We] Left it open / for the smell.” A lyrically shrewd move. We find ourselves wondering at the small growing points of sorrow in our own chests. Right then, Kunz repositions the poetic lens again and we see the father through the eyes of the speaker’s younger brother, Noah. This tertiary filter, the speaker remembering his brother remembering his father, brings an anomalous but advantageous viewpoint to the text. We discover that maybe “Fixer” is the speaker’s way of saying “father”: “plus he [the father] could fix / anything, he was amazing, leaky faucet, / done sticky door, done, lawn mower / won’t start, done.” But perhaps the speaker, the son, experiences his own transformational shift into a type of fixer by fixing or settling the affairs of his father.

This double motif of becoming appears elsewhere in the collection. In the poem “Squatters,” the speaker observes the movements of squatting neighbors, but in “Golden Gate” the speaker occupies that same taboo social position: “When the work was done, I went on / squatting in those bright upstairs rooms.”

It is, perhaps, the plainness of Kunz’s language that makes way for depth of meaning. In “Good Deal” he writes, “A stash of apples in my bag: / Galas. An Empire.” Is it a few Gala apples and an Empire apple? Or does the stash of the speaker’s Gala apples feel like a treasure, an empire? The reader is invited to explore multiple lyrical possibilities here.

Fixer is a poetry collection about ordinary people, where we come from and where we live. Home, as we see it in Fixer, is in people. It is in what we remember before fathers die. It is in apartments we squat in with thoughts of our lovers because the light is so habitable. It is in greasy lakeside confessions. But it is also in right now and giving new life: “a trellis to climb.”

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian, who received the 2023 Humanities Tennessee Fellowship in Criticism. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters and is at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.