Go Tell It in the Valley

Wrestling with God and a three-letter word

At 23, I was in search of a new land — so I went to the valley. There, in that valley, which for me was Cleveland, Tennessee, I encountered musclebound evangelical youth and painted young ladies. The ladies often used phrases like “Abba said” or “the Father’s will,” and so I assumed that they were not having sex since most of them were not yet married. The young men led Bible studies, when they were not in the weight room or on the courts, and so I also assumed that they were not having sex with the young women — or each other. I was wrong.

At that holy college, the scales finally fell from my eyes. I realized the warm sensation in my own body. It was not a yearning to be ravished, but to be held. Yet, the strictures of my Christian world precluded this holding. And so, as a last resort and maybe the only one, I began to read again. I knew that books had arms. Books could hold. Books had been my safety in the early years against the fiery darts of that three-letter word.

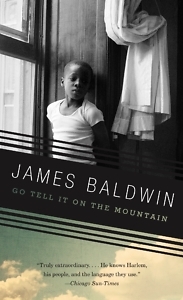

I cannot recall now whether it was by some serendipitous search or opportune recommendation, but Go Tell It on the Mountain was soon in my hands. I had never read James Baldwin, but judging by the forlorn Black boy on the cover, I knew the book was for and about me. The opening lines confirmed my thoughts: “Everyone had always said that John would be a preacher when he grew up, just like his father.” I was there, in Cleveland, and in seminary, to answer just that call — or threat. For when the saints marked you as a preacher, you could run, but you could never really hide.

The novel quickly descends into the valley — that is, into the night. Our protagonist, John, opens the church to prepare the sanctuary for that evening’s service. As he places the Bibles and mops the creaking floors, it is as though he is preparing for his own funeral. Some part of the boy will die on that threshing floor, and we will have to come to terms with what is dying for the remainder of the novel.

While John is fulfilling his duties at Temple of the Fire Baptized, he is joined by the athletic Elisha. The older boy taunts John, and their cleaning turns to wrestling. This wrestling with ‘a god’ tastes of piquant eros. I knew this quite well, the altar being not only a place of spiritual encounter, but of bodily communion. My own Elisha and I had hugged at the altar, and I could feel the cause of so much trouble, pressed against my quivering thigh. The altar was the place of small touches, too. Like the night my body betrayed me, when a reverend passed too closely before me on his way to another congregant. His behind grazed my front, and the invisible pyrotechnic sensation caused my worshipping arms to lower. I became unclean.

While John is fulfilling his duties at Temple of the Fire Baptized, he is joined by the athletic Elisha. The older boy taunts John, and their cleaning turns to wrestling. This wrestling with ‘a god’ tastes of piquant eros. I knew this quite well, the altar being not only a place of spiritual encounter, but of bodily communion. My own Elisha and I had hugged at the altar, and I could feel the cause of so much trouble, pressed against my quivering thigh. The altar was the place of small touches, too. Like the night my body betrayed me, when a reverend passed too closely before me on his way to another congregant. His behind grazed my front, and the invisible pyrotechnic sensation caused my worshipping arms to lower. I became unclean.

Shame covering shame, or uncleanness, is another theme of Baldwin’s novel. As we delve into part two, “The Prayers of the Saints,” we are led through the sordid histories of John’s Aunt Florence, his father Gabriel, and his mother Elizabeth. In each oration, following scenes of heartbreak, rape, and abandonment, we return to this same night and this same altar. We discover, essentially, what shame has brought them there.

In particular, we learn that Gabriel marries Deborah, after she has been ruined by white men. He does so because he, too, is spoiled. This is, of course, a matter of perspective — but those who are deemed broken by their communities rarely have such insight. And neither did I. At 20, I stood before an ebony congregation and declared that I was “delivered from homosexuality.” The church erupted. The minister, a woman wrapped in deep purple chiffon, slapped her Bible closed: “He preached my sermon!”

The people came down to the altar, hugged me, looked upon me. But of all the long looks that morning, one loops in the cinema of my mind: big dark eyes, teardrop-shaped face, long glossy black hair. My very own Deborah. I knew that she, too, was broken. I was an ex-gay, and she had been sexually assaulted by a relative. For a few beats, we covered each other. I saw us in a Connecticut suburb: me, a PTA dad, rushing home from the office, and my Deborah, a star attorney puckering up for a brief kiss. There were children, too — but I could never see their faces. They were tawny claymation figures in my cishet dream.

I realized, as I continued to read, that I knew in my body the Heave! Ho! that propels the novel forward. This spiritual pressing is the rhythm of the Black church, which had borne me and on whose altar I had spent many aching nights. Sometimes, I went down of my own accord, and at other times, I was taken. Rushed down by a church mother crying, Whoa! Glory, Hallelujah! And they would hold me there, wrestling with me as I wrestled with God. Some have read Baldwin’s Sister McCandless and left her in the pages. (Her name, with its feminine ess suffix, might suggest a “woman candle” or more controversially, a candle-lessness — and what would it mean if the lights are not lights at all?) But I knew Sister McCandless and the altar-time touch of her wrinkled Black hands. She tarried with John and with me through the night. And in the great gettin’ up mornin’, we were saved but in a way unfamiliar to her.

My journey to and eventual self-exile in the South gave me time. And after time, came perspective. The Southern backroads became my threshing floor. But it was just me this time. No Sister McCandless crying, “Save him, Lord!” It was just me — and the winding valley. Just me and Market Square in Knoxville. On Fridays, I would go to Union Ave Books and then to the altar of the Square. And while the sun glowed golden, I walked and prayed: Lord, make me whole. The direction of my prayer had changed; now, I was praying for wholeness against the bitter self-loathing teachings of the early years.

I must finally talk about Gatlinburg, which was for me, the end of the novel and the ascent out of the valley. In the middle of an enervating trip, with people who mistreated me, I turned to the remaining pages of the book. I saw John, answering his mother’s call down the long, dark hallway of their apartment building. The interminable night of travailing is over. John answers her in three points of light: “I’m ready.” “I’m coming.” “I’m on my way.” We do not know quite where he is going, but we know it is better than where he has been.

In that same spirit, looking down life’s long, dark hallway, I would later offer my own point of light: “Yes. I’m gay.”

Copyright © 2020 by Kashif Andrew Graham. All rights reserved. Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters. He is currently at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.