Goddesses and Coal Miners

Michael Sims remembers the bookstore where he found the world

I loved opening the bookstore alone on Sunday. I loved how it smelled — all those books with their genie-in-a-bottle dreams of love and fear, goddesses and coal miners — Sherlock Holmes on the foggy moor — barefoot Sappho — Harriet Tubman, vampires, Lassie. Often I would arrive well before noon, to have some time alone with the books. It’s misleading, how the bloody struggle of the centuries winds up distilled into a polite backstory that we can dip into before bed. Yet, despite the horrors of history and nature, I have always found books comforting, needed them as I need food or air.

I also loved the light that poured through the bookstore’s front windows — not direct light at that time of day, just the thorough clarity of midday. After their eight-minute flight from the sun, it seemed big-hearted of these adventurous photons to spot-light a humble Rand McNally road atlas to one small region of one provincial planet, and to stage-light the window’s holiday ghosts or Easter bunnies or then-current store favorites such as John Egerton’s Southern Food and Bobbie Ann Mason’s In Country. I liked how our local star’s light ennobled these benign creations by a species too often destructive. I had already read enough history and natural history to think of human life as a mayfly whirl in the sunlight. Having moved straight from working in convenience markets in my dreary hometown, I was thrilled that now my daily gift of illumination caressed Leaves of Grass instead of packets of Red Man chewing tobacco.

“You must habit yourself to the dazzle of the light,” I had underlined in my battered paperback of that volume that grabbed me and shook me awake, “and of every moment of your life.” Once I had walked up to a sunlit pond and found myself bathed in reflected wiggles of solar glory that without my interruption would have bounced back into the sky. I shimmered like Captain Kirk teleporting down to this alien planet. Afterward I felt that deliberately standing in the path of the light was the least I could do to show gratitude for life and consciousness. Opening certain books felt like striding again into that illumination. Mysteriously, I resonated to a primeval juxtaposition: late-afternoon sunlight gilding a shelf of my childhood books. I still do.

When I moved to Nashville in 1986 to work for the beloved, almost century-old firm of Mills Bookstores, I had only the offer of a part-time job. That was enough. I had fallen in love with the store and its friendly staff during visits to the city. So I also began working part-time at Nashville Bagel Company, stirring vats in which steam clouded my view of bobbing bagels. Soon Mills offered full-time.

I worked there during the period between Nancy Reagan sitting on Mr. T’s lap and Clarence Thomas sitting on Thurgood Marshall’s legacy. It was a crazy time. During the AIDS pandemic that was killing millions, a cosmetically prettified Republican president was withholding World Health Organization dues and denouncing NATO. “We’ll never sink this low again,” a friend kept moaning. It was an Ice Age of bad TV and bad hair, yet we primitives foraged and mated. Our cave paintings would have shown hawks versus doves, or an alien erupting from a human chest.

***

All of my crimes have been book-related.

First, during my backwater teen years, I subscribed to various mail-order book clubs — Mystery Guild, Science Fiction Book Club, Literary Guild — under my name, that of my mother and brother, and those of my nieces and nephews. Desperate for books in a literary desert, I was exploiting those minimum purchases and come-back-we-miss-you offers.

***

How I see books: refuge, map, uncle, guide, flying carpet. They saved my life. During my childhood with a dead father and an unstable mother who terrorized my brother and me with threats of Hell, lifting the cover of a school library book was like opening a doorway into a saner life. In the bedroom I shared with my brother when we were little, I would stand up a book on its partly open covers and walk toward it, deliberately blurring the room around it, and reach for the barely open door and walk into another world. Sometimes I even imagined closing the book’s cover/door behind me, so that anyone peering into the room would never guess where I had gone. Had I left the doorway into the other world open, Mom might have seen me trudging across the red sands of Barsoom or rowing the river with Toad and Rat.

Naturally, when I fled my rural hometown for the Big City (the bigness of cities is relative), I raced to a bookstore like a woodchuck scurrying into its burrow to escape a fox. Twenty-seven, emotionally 17, I was a crooked-toothed bumpkin fleeing pious folderol and a river baptism. Of course, as a citizen of the most religion-haunted nation west of Iran, who was moving to the headquarters of the Southern Baptist Convention, I wasn’t naïve enough to imagine that I could actually escape the psychic carpet bombing of Christian fundamentalism. I just wanted to build a life less debased by its fairy tales and torture porn.

Away from the bookstore’s display windows, softer illumination caressed bestseller stacks on the main table: Lake Wobegon Days, with its frieze of idealized smalltown America but no visible people, like the town in The Andromeda Strain after the interstellar plague. Bill Cosby’s photo covered Fatherhood with his Joseph’s Coat sweater and treacherous simper. One novel looked wrong-headedly Christmasy with Beloved in red and Toni Morrison in green. Nearby book spines wore name tags as if at a conference: James Baldwin, Virginia Woolf, Zora Neale Hurston, Carl Sagan, Nikki Giovanni, Annie Dillard. Colette and Homer wore only a given name, like too-friendly salespeople. High on the back wall, the light gleamed on framed posters of O’Keeffe’s calla lilies and Tutankhamen’s funerary mask.

On most Sundays I was the only employee at Mills. I enjoyed the backlit view of the big, quirky, font-happy sign in the righthand window,

Open NIGHTS and …

SUNDAY AFTERNOONS

as I unlocked the heavy old front door that opened onto Hillsboro Road at Acklen Avenue, rattling out the two-wheeled dolly to wrestle indoors bundles of the fat Sunday New York Times that had been plumped down by the delivery guy. Often a passerby held the door for me. Hillsboro Village, downhill from the Vanderbilt campus, was a quiet, friendly neighborhood in the late 1980s — a stratum of older residents underlying seasonal migrations of young people. Down the street, locals, country music stars, and Vandy students lined up in a concert-worthy queue before the Pancake Pantry.

I would relock the door, bring in the newspapers to stack them beside the cash register, cut the plastic twine on the top bale. Now and then an early riser had already cut this and taken a paper, leaving a dollar bill and a quarter tucked between the next couple of papers. I carried the empty drawer of the cash register back to the office, to fund it with cash from a zippered vinyl bank envelope that last night’s employee had stashed in the office. That register’s antique jingle belonged in The Music Man. When I started at Mills we used no computers, those fancy new gadgets colonizing stores and offices. The Bible of the business, Books in Print, required an annual edition of several unwieldy hardback books, each the size of a large dictionary — various shades of red and orange for authors, titles, subjects.

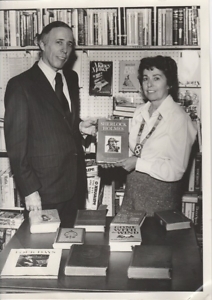

On weekdays, skinny, 70-odd Bernie Schweid would swing one of those forest-pulping tomes onto the counter with a grunt that glissando’d into a sigh. Until recently the owners of Mills, Mr. S. and his diminutive wife Adele, daughter of Reuben Mills who founded the store in 1892, were prominent in Nashville’s Jewish community and its literary community. They had also been known for fighting segregation and supporting the 1960s sit-ins. The sardonic and whip-smart Mrs. S. worked in the Belle Meade store across town, although it also had a manager, Stephanie Freudenthal, whose quick smile was so broad it seemed to close her eyes. Mills had had several other incarnations around town during almost a century. There was a Brentwood store then, whose manager, Nancy Stewart, was as witty as a fast-talkin’ dame in a ’30s farce. Eventually I worked at all three when needed. I learned to drive a stick-shift to pilot the tetchy van to transfer stock when the regular guy, droll John Neff, wasn’t around.

Having grown up in Cumberland County, a “sundown county” on the Cumberland Plateau, I arrived in Nashville knowing almost nothing about the Civil Rights Movement. The prominent Black journalist Carl Rowan, who was born in a neighboring county, had once been warned by an unusually courteous white bus driver about even stepping off the Greyhound that stopped at the station in Crossville. During my childhood in the 1960s, white-robed Klansmen with their hoods down (crewcut, farmer’s tan) would hand out pamphlets at intersections of country roads.

I fled my home turf’s propaganda for one religion and opposition to all others (First Amendment be damned) and its consequent insecure anti-intellectualism. I was tired of what seemed like a gleeful irresponsibility toward the natural world. I wanted to escape the crude sexism and racism, as well as the nonstop anti-gay jokes, that had surrounded me in high school and most of my jobs in Crossville. Although I had a stereotypically strained relationship with my mother, I could not have had a more big-hearted array of extended family, so I just wanted out of the town’s depressing attitudes.

I had grown up 25 miles from Dayton, site of the Scopes Trial, our area’s claim to fame that no one ever mentioned. Once Mom exclaimed about a reference to evolution on TV, “Don’t tell me we evoluted from a bunch o’ dang monkeys!” and schlumped around the room scratching under her arms like a cartoon chimpanzee.

I needed a new cast for the next season of my personal drama.

***

Here are my ongoing crimes that are unlikely to stop even if I go into a witness protection program:

All over the U.S., I have magnetically attracted parking tickets at bookstores and libraries.

***

As of 1986, the year I moved to Nashville, the owner of R. M. Mills Bookstores was Ron Watson, who had bought into the business over several years. He was the best boss I ever had. For decades now, he has been my mental image of a Southern gentleman — an ideal that has nothing to do with money or old family and everything to do with kindness and generosity. Ron was truly a gentle man with employees, with customers, with his sweet sister Frances who worked in the office. Ron is also gay, which made him an unwitting refutation of every vicious or mocking cliché I had been taught. How exotic this topic still seemed to many people was summed up in the title of a book that was published while I worked at the bookstore: Homosexuality: A Philosophical Inquiry. I remember thinking that I didn’t seem to run across many philosophical inquiries into heterosexuality, but then female friends schooled me on how they had to craft one every day.

The Schweids and our Jewish staff and customers, our Black staff and customers, our Muslim customers, and even other atheists I met, helped make real those people who happened to be other than white, straight, Protestant Southerners. Thus they made me feel more real too. I worked with (and am still friends with) Holly Lu Conant Rees, a petite and well-spoken woman with a fierce sense of justice; as a witty Quaker, she served unaware as an ambassador for the Christian Left, which helped me realize that my disdain for religion was too fundamentalist. So did an Episcopalian minister who would park his convertible out front to browse novels and mock the evil clown show of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker.

Customers often surprised me. One friendly guy who dropped in some nights after work would buy one trade paperback at a time and read it before he bought the next. “I’m working my way through the French moderns,” he explained. He turned out to be a butcher at a local grocery store. Having never attended college but happily reading from Pliny to Sandra Cisneros, I took this as a reminder that there were many species of bookishness.

It was mostly great fun, this job, and I recall co-workers fondly: Ruth and Jenny out front, the former angular and white and solemn, the latter none of those; married couple Jody and Barry Kammerud, she working the front and he in the back, hugging affectionately in the hallway between; smart and funny sisters Jamye and Jacquie part-time in the office; Tom House, a talented musician and songwriter who ran the shipping in the back room and held forth pungently about the injustice in the world.

Naturally I met Olympians who actually had their names on books they had written. I didn’t tell the gracious Pat Conroy how silly I found the rapist-killing tiger in Prince of Tides. Marc Brown, creator of the intrepid Arthur, charmingly talked with kids and drew in every book they bought. And I made friends among local writers. Eventually part-timer Madeena Nolan invited me to visit a Tuesday-night meeting of her writers group. They jokingly called themselves the Nashville wRiters Alliance, “the other NRA.” I read manuscripts and faced what seemed like a rigorous but collegial critique, and soon I was invited to join. From this group I learned work habits, motivation, professionalism, networking, commitment, and (most important of all) how to welcome criticism. And I made lifelong friends — another debt to the bookstore.

The staff and customers unknowingly reassured me that either A) I was not terminally weird, contrary to my mother’s complaints, or B) I had found a place where my weirdness fit right in. And I dated so many customers that Ron once said, “Sims, you should pay me.” The first woman I ever met who had untraditionally dyed hair — a brush of violet amid dark waves — kept coming in evenings to browse and chat about nature writers, and soon we were dating. We met over Loren Eiseley.

I liked Ron’s way of curbing my game-playing by merely uttering my surname. When I would sneak Medea or Oedipus Rex into the Mother’s Day display, Ron would amble back from lunch at the Pancake Pantry, notice the window without seeming to even glance that way, and as he walked by would murmur, “Sims.”

At Mills a teenager rushed in looking for the optimistically titled Death Is Not Crowded. Once a little boy sought that favorite Flannery O’Connor picture book, The Violet Bear Is Away. One parent: “My son needs a book called Charles Dickens? It’s by a guy named Copper-something?” The younger sister of a private-school student asked if we carried Tess of Ooberdooberville. A mother shepherding a flock of stair-stepped children sighed a query about a book she thought was called Clan of the Care Bears. She laughed when I showed her Jean Auel’s latest drama of two households, alike in dignity, Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon.

There were so many iconic music stars in town that even I couldn’t help stumbling over them. I would sit down next to a friendly old woman in a medical office and realize I was chatting with Sarah Cannon, better known as Minnie Pearl. Many of my family and friends were country fans, and Nashville was the mecca of that particular faith, but I didn’t care for it. Friends still remind me that when no one knew his name I saw a young Garth Brooks perform a couple of songs and remarked that this big hat ought to keep his day job.

One of Mills’s occasional customers was Waylon Jennings, who, like the guy who sold me kid jeans at Hills Department Store in Crossville, belonged to the subspecies of country boy who called everyone “honey,” even other men.

“Mills Bookstore,” I would answer the phone.

That distinctive, kind-sounding voice would say, “Hey, this is Waylon. My ole pal Johnny Cash is doin’ a readin’ there this afternoon, and I can’t be there, mainly because I’m lazy, and I wonder, honey, if you could get him to sign a book for my cousin?”

Then, when Johnny Cash arrived, he politely made his way to each of our staff to shake hands and introduce himself. “Michael,” he said quietly to me as we set up his signing for The Man in Black or one of his other books, “I wonder if my mama could have a chair?” Yes, he brought his mother, and yes, he remembered our names, at least during the event.

***

Tyrants are right.

Holding these few memories up to the light, thinking about why the bookstore was so important in my life, I am reminded that books are dangerous.

Mills Bookstores — their inventory and staff and customers — did for me exactly what today’s book-banners and enemies of honest history are worried about and trying to prevent: Mills challenged my indoctrination.

Raised Southern Missionary Baptist, drilled in piety by (actually pleasant and well-meaning) Sunday School teachers, baptized in a river by a (very kind) barber and part-time minister, punished at school for snarking through an allegedly educational film, whacked by my mother for remarking that a hippie on TV looked like Jesus, fed traditional American racism and sexism by the culture around me, I somehow grew up into a liberal, anti-racist, feminist atheist who wanted more than anything else to become, well, what he thought of as “civilized.” Hey, I could be some dolt’s cautionary fable.

Recognition of the need to hold more than one idea in your head, the very notions of literacy, tolerance, a love of learning, understanding, love of the arts, respect and compassion for those very different from yourself — for me they were inoculations against extremism and supremacy. I learned these values mostly from the subset of humanity that I think of as “book people,” beginning at Mills.

Nowadays aspiring tyrants are again demonizing teachers, silencing other voices, replacing history with propaganda. They know that books (and bookstores and libraries and other venues) will lure their village’s larval bigots away from the venerable cruelties in which they have been marinated.

***

And my last crime:

After quitting Mills for a while and living and working in nearby Murfreesboro, I moved back to Nashville and the bookstore. I felt reunited with a lost love. Then, in the early fall of 1990, Ron told us that he was forced to soon close the struggling company. Shepherding a business through financial strain must be like suffering with a chronic illness that is not visible to others until the patient dies.

I think I felt that the bookstore had dumped me. I had broken up with it first, by going away to a different job, but hey, never mind, I had returned out of love — only to get jilted. I felt sad more than angry, but I must have been childishly angry as well. I am ashamed to admit it, but as I was leaving on my last solo night shift I stole a couple of books.

Oddly, I retained enough moral fiber to steal only sale books — perhaps keeping it a misdemeanor instead of a felony in my own eyes. An ugly marked-down volume of Tacitus, which had been ignored on that table for months in favor of Tom Clancy and Danielle Steele, I just found in the ancient history section of my bookshelves. Unlike my other books, this one lacks my name and the date and location of acquisition. I guess I always knew it wasn’t mine.

Anyway, I owe Ron Watson five bucks.

***

Years later, when I showed my mother the Henry Holt catalog page for my first book, she saw that the title included the word “Darwin” and threw it in my face. I drove back to Nashville.

Six and a half years after Mills closed, Darwin’s Orchestra was published. Several friends and a few strangers who had read reviews came to launch me on a new career, including several of my former Mills colleagues. That made me happy, but I felt a kind of heartbreak that my first book’s debut, that dreamed-of personal milestone, was not held in the old bookstore in Hillsboro Village. You remember Mills, the one that used to be the center of the community, the one with the friendly, book-loving staff and the big front windows whose welcoming light caressed the books. I was already 27 when I arrived, but I grew up there.

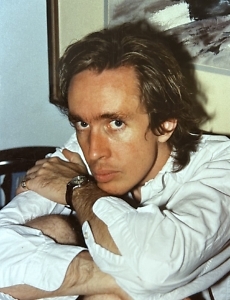

Copyright © 2024 by Michael Sims. All rights reserved. In addition to his numerous books, which include Adam’s Navel, a New York Times Notable Book, and Arthur and Sherlock, a finalist for numerous national and international awards, and his shorter writing about everything from Rachel Carson to his own son, Michael Sims has already written about one bookstore for Chapter 16.