Good Girl, Bad Girl

Writers grapple with their most memorable foibles in the new essay collection, Southern Sin

Southern Sin: True Stories of the Sultry South and Women Behaving Badly is a collection of essays about blowing it, betraying loved ones, sleeping with the wrong people, breaking the law, and, most importantly, having the nerve to fess up. In the South, this is not as easy as it may seem. The concept of sin continues to resonate with particular force here. Novelist Dorothy Allison acknowledges that force in the book’s introduction when she asks, “What is specifically Southern about sin? Do we do it better, with greater abandon? What crime of region or language marks us unique and original?”

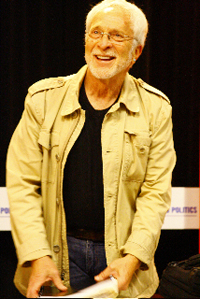

Southern Sin is edited by Lee Gutkind, founder and editor of Creative Nonfiction magazine, and Beth Ann Fennelly, poet, essayist, and co-author of The Tilted World, a novel written in collaboration with her husband, Tom Franklin. The collection offers tales of women at various stages of life who are committing a wide range of feisty, sometimes dangerous acts. Some essays highlight charming adolescent mischief. Others present young women on their own for the first time, wading into adult waters without knowing how to swim. Many describe ill-fated marriages and midlife restlessness. Then there are the stories of outlying Southern women from the distant past—rum-running moonshiners and Memphis schoolgirls bold enough to fall in love and plot their elopement.

Southern Sin is edited by Lee Gutkind, founder and editor of Creative Nonfiction magazine, and Beth Ann Fennelly, poet, essayist, and co-author of The Tilted World, a novel written in collaboration with her husband, Tom Franklin. The collection offers tales of women at various stages of life who are committing a wide range of feisty, sometimes dangerous acts. Some essays highlight charming adolescent mischief. Others present young women on their own for the first time, wading into adult waters without knowing how to swim. Many describe ill-fated marriages and midlife restlessness. Then there are the stories of outlying Southern women from the distant past—rum-running moonshiners and Memphis schoolgirls bold enough to fall in love and plot their elopement.

At every turn, these essays are full of surprises. A newly divorced woman rents a room to an adulterous couple, an arrangement which seems intriguing at first, only to unravel awkwardly. A graduate student from Michigan notices every small act of racism after she moves to Charlottesville, unready to confront her own capacity for prejudice. An unassuming teacher finds that there’s an audience—and a market—for photographs of her big, strong calves.

Many of the essays move with a sultry hip sway, putting into language all the heat and musicality of long Southern evenings. In “The On-Ramp,” Amy Thigpen’s love letter to her hometown, New Orleans sidles into view: “She doesn’t have to be the place you were born to seduce you this way. She can be the place where you feel at home even if you’re a Yankee. You’re going to succumb in the end, and she knows it with the certainty of a voodoo queen,” she writes. “New Orleans is many things, but if all of those things were simmered down to an essence, clarified like butter, what remained would be pure aphrodisiac.” Other essays describe restrictive religious upbringings—no sex, no dancing, no booze, no doubts—which ultimately provoke acts of rebellion. By any standard, these are wildly different ways to learn about the concept of misbehaving. Is it possible that these contradictions—Sunday School and Bourbon Street—have given Southerners a particular ability to recognize sin on sight?

In Southern Sin, the point of the storytelling is not confession—in a significant way, these stories only begin there. As the sins pile up, the essays begin to seem less about verboten acts and more about each writer’s attempt to make a place for her transgressions within the context of her own life history. Sometimes these acts are presented as rites of initiation—necessary passageways into the complexities of adulthood. Others are revealed like friendly secrets confided underneath beauty-parlor hair dryers. Some are examined like the artifacts of war-torn landscapes—evidence of crimes that cannot be taken back.

In Southern Sin, the point of the storytelling is not confession—in a significant way, these stories only begin there. As the sins pile up, the essays begin to seem less about verboten acts and more about each writer’s attempt to make a place for her transgressions within the context of her own life history. Sometimes these acts are presented as rites of initiation—necessary passageways into the complexities of adulthood. Others are revealed like friendly secrets confided underneath beauty-parlor hair dryers. Some are examined like the artifacts of war-torn landscapes—evidence of crimes that cannot be taken back.

The collection is at its most affecting when it explores the sins with the highest stakes—acts that put our dearest relationships, or even our lives, in peril. Such transgressions also prompt the deepest moments of reckoning. The authors never present their darker lapses of judgment glibly. Instead, they tackle the difficult task of coming to terms with them. The results are often cathartic and moving. Southern Sin offers such a range of reckoning with mistakes that it could also be seen as an anthology of forgiveness.

How do we truly forgive ourselves? These essays barrel right into the core of a daunting question. In the book’s most haunting and beautiful essay, “No Other Gods,” Sarah Gilbert illuminates the experience of sinning against ourselves—of not loving ourselves enough to choose self-respect. In this passage, she captures the powerful movement from darkness to light that can occur in forgiveness:

You have learned to say “no.” You have learned that your sin was your own thing, a self-inflicted judgment. Your day of reckoning has come and gone and your judge, prosecution, and defense were all in your imagination. You were being good and believing yourself to be bad. You reckoned wrong.

The sin is yours and yours alone. It stops with you.

You have been punished already, the sackcloth and the stoning and the tearing of hair. That’s done, that’s accounted for, that’s added up. You have been measured, mene mene, you were not found wanting by anyone but you.

Take the crown, take the treasures, take the kingdom of heaven. It is all yours. Take it now and whatever you do, submit it not to anyone.

Whether the essays are humorous or chilling, they all contribute to the book’s sense of cumulative purpose. Taken together, the cycles of confession, reckoning, and reflection create a kind of incantatory momentum, leading toward compassion. Southern Sin works well as a collection because in reading we begin to feel that we too can move toward greater forgiveness. We can believe that, even in our loneliest acts of transgression, true solidarity may be found in acts of compassion.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College, and her writing has appeared in Yemassee and Tennessee Libraries and is forthcoming in The Florida Review. She lives in her hometown, Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.