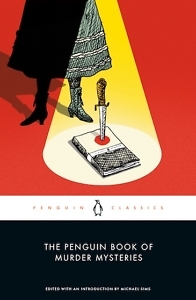

Good Old-Fashioned Murder

Michael Sims’ new anthology of short fiction presents antique whodunit gems

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on November 13, 2023. The post has been updated with new event details.

***

The origin of the detective story is, like that of many art forms, a matter of debate. Some historians credit the honor of first whodunit to the Biblical Daniel, others to a tale ascribed to Scheherazade in One Thousand and One Nights. But although the genesis of detective fiction may be shrouded in the mists of literary history, there can be little doubt that the murder mystery genre flourished in the 19th century, when classic detectives like C. Auguste Dupin, Sergeant Cuff, and Sherlock Holmes left audiences hungry for more and more elaborate crimes. In The Penguin Book of Murder Mysteries, the latest collection of short stories edited by Tennessee native Michael Sims, the celebrated author and anthologist presents 13 murderous tales. The stories span the Victorian age, illustrating the evolution of the fictional detective as he — or she — solves the vilest of all crimes.

“No doubt we are all civilized people here,” writes Sims in the book’s introduction. “We obey the law and wish each other well. Of course we do. And yet — here we are, preparing to enjoy stories about murder.” Sims understands that beginning with the story of Cain and Abel, readers have relished homicide. We as an audience want no end of artful stories about serial killers, devious villains seeking fortunes, jealous lovers exacting revenge, and any other combination that a clever investigator can suss out and put right in the end. Indeed, the idea of murder as an art form is a recurring theme in detective fiction, with killers as well as their pursuers portrayed as artists and the reader acting as connoisseur. The writer who can best provide the reader with the chill of a horrific murder, then show how the detective discovers and captures the perpetrator, will be rewarded with praise for a job well done and loyalty through many stories.

The Penguin Book of Murder Mysteries is a deliberately broad cross-section of the type, including a near-equal mix of male and female authors of varied backgrounds. Sims is expert at anthologizing little-known authors, as he has done in previous works that include Frankenstein Dreams, The Phantom Coach, and The Penguin Book of Victorian Women in Crime. It is thus no surprise that most of the authors presented in this collection are unknown beyond the world of detective fiction mavens yet are truly talented storytellers. Sims seems to delight in choosing the entries, noting that “In planning a cocktail party or anthology, I select the invitees based upon the likelihood that some may be even more interesting in juxtaposition than in my previous individual encounters with them.”

The Penguin Book of Murder Mysteries is a deliberately broad cross-section of the type, including a near-equal mix of male and female authors of varied backgrounds. Sims is expert at anthologizing little-known authors, as he has done in previous works that include Frankenstein Dreams, The Phantom Coach, and The Penguin Book of Victorian Women in Crime. It is thus no surprise that most of the authors presented in this collection are unknown beyond the world of detective fiction mavens yet are truly talented storytellers. Sims seems to delight in choosing the entries, noting that “In planning a cocktail party or anthology, I select the invitees based upon the likelihood that some may be even more interesting in juxtaposition than in my previous individual encounters with them.”

Thus he presents a group of authors who have in common only the ability to surprise and chill with their words; writers who, presented in chronological order, provide a history lesson in murder fiction. A couple of important firsts are found in the collection, including, in Sims’ words, “the holder of a cherished title … ‘first female detective.’” “The Judgement of Conscience,” published in 1864 and ironically written by a man, features a detective who is herself mysterious, using only her initial, Mrs. G.

Also showcased is a story by Charles W. Chesnutt, who, Sims notes, “left behind a hugely influential legacy as a pioneer Black writer.” The Sheriff’s Children (1889) is not just a murder mystery but a commentary on late 19th-century race relations.

For whatever reasons, most of the authors in The Penguin Book of Murder Mysteries are not widely remembered. Yet these contemporaries of Poe, Collins, and Doyle were important contributors to the genre. They created clever, memorable characters who employed the technologies of their era, thrilling readers with the awful crime, the cat-and-mouse chase, and the triumph of order over chaos. Sims notes the importance of the cultural desire for resolution, observing that mystery novels were “popular during World War II among the crowds hiding in the Underground from Nazis blitzing London.” The world is still a dangerous place, which perhaps explains why this new collection will find a willing audience almost two centuries after the earliest of the stories was published.

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than 30 years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and an historian by avocation.