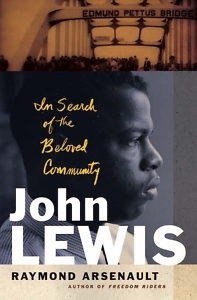

Good Troubler

Raymond Arsenault offers the first comprehensive biography of civil rights icon John Lewis

With John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community, Raymond Arsenault, professor emeritus of Southern history at the University of South Florida, has produced the first comprehensive biography of the famed civil rights leader and longtime member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Emerging from a poor farming community outside Troy, Alabama, Lewis rose to prominence with the 1960 Nashville lunch counter sit-ins and dozens of protest events that followed, including the Freedom Rides and the infamous “Bloody Sunday,” when he received a near fatal beating on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Later, during more than 30 years as the representative from Georgia’s 5th district, Lewis became known as the “Conscience of Congress,” and he was still engaging in the nonviolent resistance he called “good trouble” just six weeks before his death in 2020 at the age of 80.

Emerging from a poor farming community outside Troy, Alabama, Lewis rose to prominence with the 1960 Nashville lunch counter sit-ins and dozens of protest events that followed, including the Freedom Rides and the infamous “Bloody Sunday,” when he received a near fatal beating on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Later, during more than 30 years as the representative from Georgia’s 5th district, Lewis became known as the “Conscience of Congress,” and he was still engaging in the nonviolent resistance he called “good trouble” just six weeks before his death in 2020 at the age of 80.

“Maintaining a healthy level of scholarly detachment is always a challenge when writing about an admirable figure like Lewis,” Arsenault admits in his preface. “But it is especially difficult when the author both knows his subject personally and shares many of his beliefs.” The biographer first met Lewis in 2006 at a reunion of the Freedom Riders. “There was a quiet shyness to him that magnified his charm,” Arsenault recalls. “To my surprise, he had a soft conversational voice that contrasted with the soaring oratory he often displayed in the public arena.”

Lewis’ first formal act of protest occurred when he was 20 and attending the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville. Influenced by radio sermons from Martin Luther King Jr., Lewis helped organize the first student-led sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters in Nashville department stores. Arsenault calls the sit-in on February 27, 1960, which led to mass arrests, a “turning point for Nashville’s Black community, much of which rallied behind the arrested students.” As one of 82 arrested that day, Lewis was shoved into a crowded paddy wagon. “Now I knew. Now I had crossed over,” Arsenault quotes Lewis as recalling later.

In the spring of 1960, “the movement in Nashville, as in other centers of activism, was still in infancy, and no one knew where it was headed. But [Lewis] knew he wanted to be a part of this unfolding story of liberation, not just as a stage of his college-age transition to adulthood but as a lifelong commitment.” With that commitment, Lewis began six decades of the “good trouble” that fills the remainder of the book. In scenes that are vivid yet scrupulously researched — as attested in over 50 pages of chapter notes — Arsenault details the various organizations, personalities, triumphs, and setbacks Lewis encountered during key moments of the Civil Rights Movement.

One such event began a few months after the Nashville sit-ins, when a handful of students, including Lewis, became the first “Freedom Riders” willing to risk their lives on integrated bus rides through the Deep South. As they were beaten and arrested in several states, the protest drew national attention and soon expanded to 436 riders — and a thorn in the side of the nascent Kennedy administration. As author of the 2007 book Freedom Riders (a tie-in to an episode of the PBS series American Experience), Arsenault had already interviewed dozens of surviving protestors, politicians, and others involved in the campaign. The scope of detail and actions he assembles for the biography cinematically profiles all the major characters involved — not just Lewis.

By the time the book gets to the 1965 voting rights protests in Selma, the action is at fever pitch. When Dr. King tries to breach the color bar at the city’s whites-only Hotel Albert, a white supremacist begins kicking and punching him. Lewis, who is standing nearby, grabs the attacker, “immobilizing him with a bear hug.” A keen proponent of nonviolence, Lewis later explained that “at that moment something shot up in me … something protective, something instinctive.” The subsequent “Bloody Sunday” confrontation between unarmed protesters and state troopers on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge served as the opening scene of the best-selling March trilogy, a series of graphic novels Lewis wrote with co-authors Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell beginning in 2013. Younger readers who may know Lewis and the Selma story from the series can follow a literal blow-by-blow of the dramatic encounter in Arsenault’s biography.

Yet the book’s most relevant — and prescient — chapters may be the later ones covering Lewis’ final years in Congress. During the 2016 presidential race, Donald Trump’s rhetoric reminded him “of the no-holds-barred politics of the factional leaders who once presided over the Jim Crow South.” As Lewis “witnessed the Republican Party’s complicity in Trump’s abandonment of common decency and the traditional norms and responsibilities of governance, he had the sinking feeling that American democracy itself was slipping away.” He thus leads 23 other Democratic members of Congress in boycotting Trump’s inauguration and in later opposition to many of Trump’s policies.

“Part of his rationale for making ‘good trouble’ was to bring the nation closer to the realization of its professed ideals,” Arsenault writes. Diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer in December 2019, Lewis spent his final weeks championing that cause. To its last page, John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community presents not only the definitive history of an admirable American, but a gripping account of an American struggle for freedom that continues today.

Michael Ray Taylor is the author of Hidden Nature and other books. He lives in Arkansas.