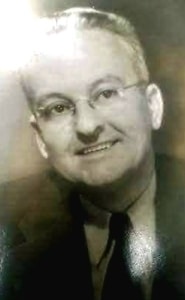

Grandfather in Black and White

He taught a child of the 1950s that anything in life might be new and exciting without automatically being better

A handsome gentleman with a ready smile, he rejected unkindness to anyone in any circumstance as a viable option. He dressed nattily and never left home without wearing a hat. Although I was only 14 when we lost him in 1963, he imbued me with one of the most constant currents in my life. Perhaps I would have gotten there on my own, but I think he had a lot to do with my becoming a passionate moviegoer.

He was in the movie business. He wasn’t a famous actor, successful director or screenwriter, or wealthy mogul, but he had an unmistakable touch of glamor about him. He owned a few theaters in Birmingham and New Orleans. Though by the late ‘30s they had become solely movie houses, in the ‘20s they doubled as vaudeville venues and cinemas. My grandfather’s theaters were among the few that booked both white acts and African-American vaudeville circuits. I was too young to know enough before he died to ask about those days, but my father later passed along some of the more indelible images and events of his childhood. Though he may not have been allowed to go see Bessie Smith’s show, he recalled watching with his younger brother through the banister late one night as Ethel Waters, then in her early days as “The Jazz Baby,” sipped bathtub gin and sang along with some of her band members in my grandparents’ kitchen after a show. He also remembered a teenaged Ginger Rogers being closely shepherded by her mother backstage and Bill “Bo Jangles” Robinson laughing and telling my 12-year-old father during an offstage rehearsal break that he was “the slowest white boy I ever tried to teach how to dance.”

My grandfather lost almost everything in The Crash. In 1929, there was a large house on Red Mountain with terraced azalea gardens overlooking Birmingham, an urban-chic apartment upstairs in back of the theater, a Cadillac and a Pierce-Arrow, and a cabin with a sleek boat on the Warrior River. My father, a high school senior then, and his younger brother had their own red damask-and-gilt box — first up, stage-left — at the theater and were apparently “rounders” of the first order. (My father remembered having his school ring and two fraternity pins in circulation at the same time.) Within months my grandfather had lost his ownership and most of his investments and was reduced to managing two theaters for his former partner. The rest of his career was a slow — and never completely recuperative — rebuilding. He probably had many reasons to be a bitter, or at least severely disappointed, human being.

By the time I came to know him, there was only the perennial kindness, the easy smile and cheerfulness, and the $5 tips for the servers who carried our Sunday lunch trays to our table at the grand downtown Britling Cafeteria.

He had a constant, apparently unquenchable, sense of wonder. Perhaps he saw something in my eyes. I only know he talked with me not as if I were 6 or 10, but as a person, a person capable of seeing, hearing, thinking, appreciating, making distinctions. Whenever I spoke of the latest films I’d seen in Memphis, he listened with intensity and asked engaging questions. Better yet were our family visits. Then I would be taken to one of his theaters where I was not only treated to anything I wanted in the glowing concession counters, but was greeted by his staff as though I were a little prince. Later, he would listen to my reactions to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, To Catch a Thief, or Damn Yankees! and — with both great fun and seriousness — compare and contrast them with other films, or books I might be reading, or films of the past. He always urged me to be open to different ways of seeing and appreciating film. Most important, he taught a child of the 1950s that anything in life, including films, might be new and interesting and exciting without automatically being better.

Of course I was avid for color. Color is seductive and color is life, and who would want a world devoid of daffodils and undistracted by the fathomless blue of October skies? It would have been impossible for anyone whose earliest movie memories included those Technicolor spectacles of the ‘50s not to have an appreciation of color in film. When Gordon MacRae lopes into the frame on horseback singing that the corn around him is as high as an elephant’s eye, our disbelief doesn’t have to be willingly suspended — we pop it with wanton insouciance like a gum bubble. And when Grace Kelly and Cary Grant tear along the Grande Corniche in that convertible, we feel her pink scarf streaming back from that swan neck and see, far below, the Mediterranean as a coruscation of teal.

But Grandpa bequeathed to me an openness for a breadth of experience, and that’s when I began to learn that film was not solely “the latest thing” showing at my neighborhood theater or at the last of the great palaces downtown; it was a fascinating and utterly absorbing continuity of life. Before I could intellectually grasp the concept, he gave me my first intimation that in the entirety of human history, we were privileged to be the first who could witness themselves “alive” on the screen and that this was a tremendously significant new way of experiencing social history.

He made sure I knew about “The Late Show” and inveighed upon my parents to let me stay up on weekend nights to watch. I was drawn and drawn again to these other films, the ones that were becoming sparser by then, the black and white ones shown on WREC, one of our local Memphis stations, and which I had all to myself late on those nights as I sprawled on the den floor or sofa, gorging on them, giddy with the pale flickering. It was a densely inhabited solitude.

When you’ve watched Atticus Finch at work in that courtroom, you have no need of remembering the various tints of small-town suits or shirtwaists, complexion, or hair — you’ve felt the tension and the seething creep of sweat, and you never forget sticking to those wooden benches, waiting for justice to break. Once you’re introduced to Edward G. Robinson as Rocco in Key Largo, smoking a cigar in the bathtub, you do not have to know the colors of his henchman’s tie as he stands at the door to know it is garish — and you will always recognize the uneasy cruelty of thugs when you see it and remember that soap suds can be the slime of pure evil. When in The Best Years of Our Lives your breath catches along with hers as Myrna Loy knows for a split second before she knows and turns from the kitchen to see Fredric March at the end of that hall, it’s because an entire universe comprised of them and you, and complete in itself, is catching its breath.

When I watch a black and white film, I often feel my grandfather close at hand. I now understand that being a Romantic and facing up to harshly delineated necessities are not always mutually exclusive. When my wife and I watch that last scene of Now, Voyager and Charlotte tells Jerry not to “ask for the moon when we have the stars,” we don’t have to wonder about the shade of Davis’ lipstick or of Henreid’s jacket or what color the draperies may be — there is nothing but the final swell of Max Steiner’s theme, the two glowing cigarettes lit from one, their “one small strip of territory we must protect,” the window opened to the night, and their eyes fixed on one another.

Forever.

Copyright©️ 2025 by Hadley Hury. All rights reserved.

Hadley Hury’s new novel is At the Villa Borago. He has written on film and theatre for a number of publications and digital platforms. His work includes a novel The Edge of the Gulf (2003), a collection of short stories It’s Not the Heat (2007), and a poetry collection Almost Naked (2018). He was associate professor in film at the University of Memphis, and guest lecturer on film at Memphis College of Art, Rhodes College, and Brooks Museum of Art. He is married to Marilyn Adams Hury and they live in Memphis.