Grounded

A new book profiles six families who have partnered with the Land Trust for Tennessee to preserve their land for future generations

In 1998, deep into Phil Bredesen’s second term as mayor of Nashville, he and his wife, Andrea Conte, invited a group of environmentally minded friends and colleagues to their home for a social evening with an agenda: to discuss ways of preserving green spaces in Davidson County and beyond. Specifically, Bredesen and Conte wanted to float the idea of bringing land trusts—a concept that had long worked in other parts of the country—to Tennessee. Through the use of conservation easements—tailor-made legal documents that specify how a tract of land can be used in the future—landowners can secure the preservation of their property while also maintaining ownership and the right to designate heirs. The land remains in the family, in other words, but its future use is limited by the terms set out in the conservation easement.

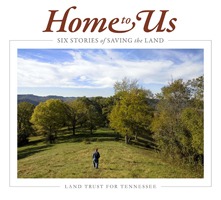

The Land Trust for Tennessee was officially chartered in 1999 to “preserve the unique character of Tennessee’s natural and historic landscapes and sites for future generations.” So far, more than 200 landowners have partnered with the Land Trust to create conservation easements that now protect 75,000 acres in Tennessee—family farms, historic buildings, rural lands, even an arboretum. “Collectively, these ‘saves’ guarantee that an expanding portion of our state’s geographic and historic treasures, some of which are older than the state itself, will still look the same centuries from now,” writes Jeanie Nelson, president of the Land Trust for Tennessee, in the introduction to Home to Us: Six Stories of Saving the Land.

A lavish new coffee-table book, Home to Us features the stories of six very different families who have preserved their lands through conservation easements. The book was written by Varina Willse and includes photographs by Nancy Rhoda. Willse recently answered questions about the project from Chapter 16 via email.

A lavish new coffee-table book, Home to Us features the stories of six very different families who have preserved their lands through conservation easements. The book was written by Varina Willse and includes photographs by Nancy Rhoda. Willse recently answered questions about the project from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: You grew up on a sixth-generation Robertson Country farm yourself, so I can see that this book was the perfect project for you, but how did the Land Trust come to recognize what you would bring to the book?

Varina Willse: It was really a case of being in the right place at the right time, as so many things are. I happened to be at a Land Trust event, back in the fall of 2009, because a friend of mine, Vadie Turner, was hosting it and invited me. At that gathering, I got into a conversation with Jeanie Nelson, the president of The Land Trust for Tennessee, and she was pointing out the landowners in the crowd, growing more and more excited by telling their various stories—explaining how so-and-so had a father who had been struck by lightning on his farm, and so-and-so who had ancestors who fought in the Civil War on his property, and on and on. The more she talked, the more I stood there thinking: she needs to do a book. When I said so, Jeanie turned it around immediately and said, “You need to do the book!” The next thing I know, she is on the microphone, telling the crowd about it.

Even still, it might have been one of those cocktail conversations that don’t carry past the party. But I was expecting twins at the time and had already decided to quit full-time teaching in order to raise them. I was at this crossroads in my life, and I knew I wanted to write more, and then this conversation occurs, and something on the landscape shifts. I remember leaving that night—underneath this radiant sunset—and feeling like I had been at that party for a reason.

Chapter 16: I’m struck by the mix of stories in Home to Us—from tiny hardscrabble farms that have been in the family for generations to a lakeside architectural showplace nestled among country-music stars’ homes. Are there any common qualities generally shared by people who partner with the Land Trust?

Chapter 16: I’m struck by the mix of stories in Home to Us—from tiny hardscrabble farms that have been in the family for generations to a lakeside architectural showplace nestled among country-music stars’ homes. Are there any common qualities generally shared by people who partner with the Land Trust?

Willse: These are people who are grounded, literally. They know who they are, they know where they come from, and they know what virtues they stand on—one of which is the conviction that there is nothing more valuable than land. I like the way Nancy Rhoda, the book’s photographer and now my dear friend, explains it: “Each family has a connection to the land as though it were a family member. They have an understanding of the importance of nurturing the land through its use, tending its care, and enjoying its beauty. They know the nature of their land is alive; it changes, it grows, it needs protecting.”

Chapter 16: The “Honor Roll of Land Trust Partners” listed in the back of the book contains more than 200 names, includes both tiny parcels (less than half an acre) and giant tracts (more than 4,000 acres), and reaches across much of the state. From such a bounty, how did you decide which families to profile?

Willse: The six families we chose for the book are all in Middle Tennessee, primarily for logistical reasons since Nancy and I needed to make multiple visits to each family. We needed families who live on their property most if not all of the time and who are actively engaged with it. And then, we wanted to be sure to represent the diversity of people who make this choice: diversity of age and socioeconomic status, diversity of acreage protected, diversity of usage of the land. We wanted to dispel any myth that this choice is limited to a certain kind of person.

Chapter 16: In fact, these profiles are often multigenerational portraits, featuring not only the surviving generations but also reaching back into family history through stories and photographs. This book seems to have been a work in progress for several years: what was it like to become so immersed in the love stories and hardships—and, in some cases, family disputes—of total strangers?

Chapter 16: In fact, these profiles are often multigenerational portraits, featuring not only the surviving generations but also reaching back into family history through stories and photographs. This book seems to have been a work in progress for several years: what was it like to become so immersed in the love stories and hardships—and, in some cases, family disputes—of total strangers?

Willse: You are right: it was a work in progress for several years, starting just after my twin daughters were born. Because I could actively work—meaning work at the computer, as opposed to work in my head—only during a limited time slot each day, a.k.a. naptime, it took me a long time to complete each chapter. From the time of the interviews to the time it took to transcribe those hours and hours of tapes to the time it took to organize the material, then draft it, then revise it—collaborating with Nancy all along the way—several months would have passed. It was a long time for the story to be inside me unwritten and alive, so I would wake up in the middle of the night thinking about it, and I would feed my kids thinking about it.

In some ways, it was tiresome. It would have been nice to dive in and be done with it. On the other hand, having all that time to live with the story inside me gave me a chance to really process it. Processing the stories, I tried to immerse myself in them more analytically than emotionally. Of course, I was moved by them—how could we not be?—but I tried not to get too weighted down by my own sense of compassion. Because I had so much to handle in my own life, I honestly didn’t have enough emotional energy to do that and still be productive. So, I tried to focus on how I could best articulate the stories in a way that would be careful and true.

Chapter 16: In most cases, the children and grandchildren of your profile subjects fully supported the decision to preserve family land, but you hint that the decision to partner with the Land Trust was a source of controversy in a couple of the families you profiled. Without betraying any confidences, can you describe what people generally objected to when objections were raised?

Willse: Any decision that is lasting, that in this case is everlasting, is a big decision. And I think some people are, understandably, scared of signing away possibilities: the possibility of getting the most money for it, or the possibility of building on it in a different, unforeseen way, for example. But signing away the possibility of that land’s ever being developed—that’s the bottom line for the many families who make this choice. Nothing is more important to them, because it allows them to protect their land—to protect the land in our state—and save it for future generations. That is how home to me becomes home to us.

Willse: Any decision that is lasting, that in this case is everlasting, is a big decision. And I think some people are, understandably, scared of signing away possibilities: the possibility of getting the most money for it, or the possibility of building on it in a different, unforeseen way, for example. But signing away the possibility of that land’s ever being developed—that’s the bottom line for the many families who make this choice. Nothing is more important to them, because it allows them to protect their land—to protect the land in our state—and save it for future generations. That is how home to me becomes home to us.

Chapter 16: Some of these families set aside certain portions of their property for family members to build on in the future, even under the conservation easement. Is there a fair amount of individuality a landowner can ask for when creating a partnership with the Land Trust?

Willse: Absolute individuality. People make the mistake of thinking that these landowners give their land to the Land Trust or give up all rights to shape it in any way, but that’s not correct. Each conservation easement is custom-made to protect the important conservation aspects of the land as well as the needs and wishes of the landowner donating it, so each one is different. A family works with The Land Trust to identify site(s) they want to set aside for future homes, for example, or they can designate what sections of forest can be cut for timber, if any. They work with the Land Trust to identify all the specifications. It is a time-consuming process because it is tailor-made, but that is what makes it appealing and successful.

Chapter 16: Is there a single event or episode that truly encapsulates for you the experience of walking these lands with the people who have secured their protection?

Willse: The book is dedicated to Lucy Knight, who passed on between the time we first sat down with her and her husband Dewey and the time we finished the book. She and Dewey had been married sixty-two years, surviving the loss of their community and the loss of their daughter together. Losing her, Dewey might not have been able to go on. But he could, and the reason he could—he told me—was because he had the farm. He was the first of the six families that I heard from once the book came out, and when he called to tell me how pleased he was with it and how moved he was by it, he said that it was the farm that had helped him endure after her death. That was perhaps the first time that I understood fully what the book was really about—that our stories and our land can save us, when we have the heart and the courage to save them.