Hard Honest Comedy

Padgett Powell’s new collection of nonfiction takes you inside the mind of an unconventional novelist

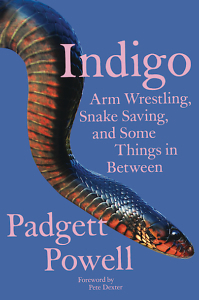

Fans of Padgett Powell’s fiction expect to find in Indigo, his first collection of nonfiction, quirky characters and inimitable prose, and they won’t be disappointed. Another set of readers, unfamiliar with Powell’s catalogue but drawn to this book by ecstatic reviews and superlative blurbage (“one of the few truly important American writers of our time,” says Sam Lipsyte), have a treat in store.

Perhaps the latter group will believe they have discovered an unrecognized genius and will ballyhoo Powell-as-essayist. Debates will erupt, as they did with David Foster Wallace, on the question of whether Powell is better as journalist or novelist. It’s a conversation worth having. (The correct answer is novelist.)

The first two elements of Indigo’s subtitle — “Arm Wrestling, Snake Saving” — refer to the collection’s bookends, long pieces about Cleve Dean, the 700-pound world arm-wrestling champion from Pavo, Georgia, and about Powell’s quest to hold an indigo snake before the endangered species vanishes completely. While those pieces are marvels in their own right, exemplars of the magazine profile and personal narrative (or “memoiritis,” as Powell calls it, a disease spreading through the literary populace, “more frightening than Ebola”), they are anomalies here. Most of the pieces are shorter, quirkier, and uncategorizable.

What distinguishes a Powell character from the common run of humanity? The key quality has nothing to do with age, sex, race, or religion; rather, it’s an ontological difference: They live in Powell’s sentences. They may share names with real-world figures, but, reborn in Powell’s prose, they acquire enhanced significance. “Cleve Dean is god-like, if a god can be invariably agreeable,” Powell writes. “He is an icon and an oracle people want to be near physically, and historically he is Big Daddy.”

The people Powell admires seem larger than life, yes, but mainly other than life. This collection is visited by Powell’s pantheon of ruling spirits. He refers to Donald Barthelme, his creative writing professor at the University of Houston, as “God here in Houston … We were lowly sun-addled Aztecs to his Quetzalcoatl.” Powell refers to Flannery O’Connor as “the goddesshead.” “I revere her in a way that she would also advise against, in fact would probably repudiate outright, hard.”

The people Powell admires seem larger than life, yes, but mainly other than life. This collection is visited by Powell’s pantheon of ruling spirits. He refers to Donald Barthelme, his creative writing professor at the University of Houston, as “God here in Houston … We were lowly sun-addled Aztecs to his Quetzalcoatl.” Powell refers to Flannery O’Connor as “the goddesshead.” “I revere her in a way that she would also advise against, in fact would probably repudiate outright, hard.”

On the Olympian peak, Powell avers, sits Peter Taylor, who paradoxically was modest and “Southern-courtly” in person. Powell, for 35 years a “schoolmarm” of creative writing at the University of Florida, included Taylor on his syllabus alongside “wacky mode” writers such as Thomas Bernhard, Flann O’Brien, Beckett, Kleist, and Diderot. Every year, “students testified that it was Peter Taylor they most enjoyed, Peter Taylor they wanted to write like. I never understood it, I understood it.”

What you won’t get in Powell’s essays is a universal theory of art. As a schoolmarm, he eschews “literary criticism or even review criticism; in schoolmarming what we do is ask how might this writing be different so that it is not this bad next time.” When Powell takes a stab at aesthetic theory, he quickly loses interest. “Bill Wegman takes oaf to the second power, where it is not oaf,” Powell says of the famous Weimaraner photos, “and part of the way he does this is via line art as strong as that of Picasso and his bulls. Let’s move on.”

Powell uses profiles of writers to offer his take on what makes writing work. Reflections on O’Connor lead him to the only wisdom he offers young writers, that “writing is controlled whimsy.” In a tribute to Denis Johnson, Powell tenders “the highest praise I can with respect to writing and with respect to a writer: the best is hard honest comedy, and Denis Johnson was the best at it.”

Powell sometimes requires neologisms to describe the traits he admires. In his appreciation of Taylor, Powell admits to having taken a circuitous route. “I have daftly peripatetted about in all this irrelevance now for pages in the hope of sneaking up on relevance,” he says. “This does not always work, and one may appear merely daft.” Finally, Powell claims that Taylor’s fiction embodies an essential, John Irving-esque truth: “Life is a surface of propriety with an undertoad of the naughty under it.”

Regardless of the ostensible subjects of these essays — art, travel, dead dogs — Powell’s abiding concern remains himself, not narcissistically but as a product of middle-aged self-awareness. In Bermuda, the experience of rubbing a barracuda “is something that would thrill a boy to death and it is almost making me a boy again to do it and I am fifty-nine-and-eleven-twelfths-how-did-this-happen-to-me old.”

Indigo is worth the price solely for the foreword by Pete Dexter, Powell’s longtime friend and admirer. Dexter’s long, rambling essay is fitting homage to a writer Dexter compares to Willie Mays. “My own literary criticism,” Dexter writes, “is that, so far, whatever Padgett writes, I wish I’d written it too.”

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.