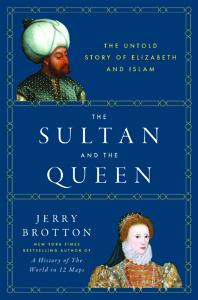

Her Majesty’s Ottoman Enterprises

Historian Jerry Brotton talks with Chapter 16 about England’s groundbreaking relations with Islamic empires

Jerry Brotton wants readers to think big. In A History of the World in Twelve Maps (2012), he argued that the global perspectives offered by cartography, from the cuneiform tablets of ancient Babylon to the eerie precision of Google Earth, are not objective representations of the world but creative projections based on our limited, inevitably self-centered understandings. “Mapmakers do not just reproduce the world,” Brotton wrote, “they construct it.”

With The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam, Brotton examines the way English diplomats managed to open trade relations with Islamic leaders. At a time when Protestant England was blocked from trading with Europe’s Catholic nations, Elizabeth managed to negotiate deals that allowed English companies to trade with Turks, Moors, and Persians from the southern Mediterranean and the Middle East. The religious differences between the cultures, Brotton points out, remained secondary to mutually beneficial commerce.

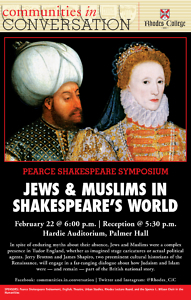

Jerry Brotton is a professor of Renaissance studies at Queen Mary University in London. In advance of his appearance at Rhodes College in Memphis, he answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: The Sultan and the Queen appears at a time when tensions are once again mounting between the West and Islamic nations. What lessons can contemporary leaders draw from Elizabeth’s experiences?

Jerry Brotton: Don’t stop people of different faiths and beliefs from crossing your borders because it never works. The irony is that empires like the Ottomans prided themselves on their ability to absorb and assimilate multi-confessional, polyglot communities. To limit, isolate, and demonize particular religious or ethnic groups was seen as a sign of weakness, not power. Even when the Elizabethan state issued edicts trying to deport what they called “blackamoors” (mainly Muslims from North Africa), it never stuck because, guess what, everyone realized it just wasn’t workable!

Chapter 16: Elizabeth herself is a fleeting presence in this book; she operates primarily through intermediaries, often in order to maintain plausible deniability. How skillful was her leadership in trade and diplomacy?

Brotton: Elizabeth was a survivor who pursued a very shrewd policy of realpolitik; whatever was needed to ensure the Tudor state’s survival—and its existence often seemed to face terminal threats—Elizabeth would support it. This held true for so many of her policies in religion and domestic policy and also includes her approach toward political, commercial, and even military alliances with the Islamic world.

Like most rulers she acted through intermediaries but her key advisers for many years were Francis Walsingham, Cecil Lord Burghley, and the Earl of Leicester. All supported and in some ways led the state’s pro-Islamic policy, from Walsingham’s support of trade with the Ottomans to Leicester’s de facto running of the Barbary Company trading in what would today be called Morocco. But ultimately Elizabeth sanctioned the policy as a way of ensuring a bulwark against Spanish and Papal Catholic aggression against her rule, and arguably it worked.

Chapter 16: The Sultan and the Queen details the activities of a number of Elizabeth’s emissaries, many of whom were colorful figures in their own rights. Aside from the comically knavish Sherley family, is there another character who deserves a book of his or her own? (My vote is for Peter Baker, a servant of Edmund de Vere who nearly derailed Anglo-Ottoman relations through mindless cupidity.)

Chapter 16: The Sultan and the Queen details the activities of a number of Elizabeth’s emissaries, many of whom were colorful figures in their own rights. Aside from the comically knavish Sherley family, is there another character who deserves a book of his or her own? (My vote is for Peter Baker, a servant of Edmund de Vere who nearly derailed Anglo-Ottoman relations through mindless cupidity.)

Brotton: William Harborne, England’s first ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in the late 1570s, is an extraordinary figure, although he has been written about to some extent. My other favorite is Anthony Jenkinson, a young textiles merchant who in the space of two decades extracted the first English trading privileges from a personal meeting with the Ottoman sultan, Suleyman the Magnificent in the 1550s; was the first English merchant to meet Ivan the Terrible as a representative of the new Muscovy Company; and also reached Persia in the 1560s, where he met the Shah. He lived to return home and tell stories of his encounter with a Tsar, a Shah, and a Sultan, as the one of the toughest and most intrepid of all English travelers to the Muslim world.

Chapter 16: Your book examines the way English playwrights, fascinated by tales of adventure in the Ottoman and Barbary Empires, portrayed Muslim characters on stage. How did Shakespeare’s Turks and Moors begin to change those portrayals?

Brotton: Turks, Moors, Saracens, and Persians are all synonyms for “Muslims”—a word that enters the English language only in the later 17th century—and they are all the subject of many plays by Elizabethan dramatists, including Shakespeare. These depictions are neither exclusively positive nor negative; I think that Shakespeare understood the ambivalent power of such characters on the stage, when everyone knew the English were in league with Moors and Turks.

So Aaron the Moor in Titus Andronicus (c. 1592) is an evil “blackamoor,” but just three-to-four years later, the Prince of Morocco in Merchant of Venice is a noble, rather melancholic Moor. Five-six years later Shakespeare again returns to the character of the Moor with Othello, which allows him to draw on both versions of the evil Moor, and the noble one. The audience grasped that they were being asked to oscillate between fear and admiration for the convert from Islam: just as many Elizabethans were doing in their relations with Muslims across North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East.

Chapter 16: The English defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, aided by a fortuitous storm, is a famous example of the role of chance in determining the course of history. What role did contingent factors play in the decades-long relationship between Elizabeth and the Ottoman sultans?

Brotton: The English ambassador to Istanbul, William Harborne, was told by the English spymaster Francis Walsingham to encourage the Ottomans to remain hostile toward the Spanish throughout the 1580s in the hope of diminishing the size of the Armada that everyone knew would one day sail against England. Harborne certainly persuaded the sultan to refuse a peace treaty with the Spanish, who were keen to neutralize the Ottomans so they didn’t have to fight on two fronts against Protestants and Muslims. (Both were seen as heretics by Catholics, two sides of the same heretical coin.) None of this helped the Spanish cause.

Chapter 16: Elizabeth’s court repeatedly drew parallels between Islam and Protestantism, as if their similarities made them natural allies. The Sultan and the Queen makes it clear that such claims were primarily rationalizations for establishing trade partnerships. To what extent did the sultans perform the same justifications, defending trade with Protestant England as in keeping with Islamic principles?

Chapter 16: Elizabeth’s court repeatedly drew parallels between Islam and Protestantism, as if their similarities made them natural allies. The Sultan and the Queen makes it clear that such claims were primarily rationalizations for establishing trade partnerships. To what extent did the sultans perform the same justifications, defending trade with Protestant England as in keeping with Islamic principles?

Brotton: Both sides made superficial claims to share similar religious beliefs: the power of their holy books, the refusal to believe in intercessions (like saints) or the worship of icons (which both saw as idolatry). The Ottomans were similarly strategic in fomenting conflict between Catholics and Protestants in a classic divide-and-rule strategy. But while all this pragmatic political maneuvering went on, people on the ground living with the consequences had to accommodate each other’s beliefs: Protestant English men and women lived, worked, and traded with Muslims, and these everyday transactions went far beyond public policy.

Chapter 16: What do you think was the breaking point in trade and diplomatic relations with the Islamic empires?

Brotton: Isolation from Europe! Does that sound familiar? Although the Anglo-Islamic alliances saw various commercial initiatives, such as the creation of joint stock companies like the Muscovy and Levant Companies, by the time Elizabeth lay dying in 1603, the country was close to economic collapse due to its isolation from Europe’s markets. The theological iron curtain imposed by the Reformation and Elizabeth’s excommunication in 1570 had to be lifted, and it was Elizabeth’s successor, the Stuart King James I, who agreed to a peace treaty with Spain in 1604 that allowed the English to travel and trade once again with Europe. It’s a lesson we do not seem to have learned.

Chapter 16: For three decades (at least) of Elizabeth’s reign, England was continually on the brink of disaster. Your book does not indulge in counter-factual hypotheses, but one senses that England might not have survived the sixteenth century as an independent nation. What does The Sultan and the Queen teach us about the qualities a country must have to survive during crises?

Brotton: It’s a difficult question as the qualities that define a successful absolutist monarchy are very different from those that characterize our constitutional representative democracies in the West today. But certainly a level of pragmatism and toleration is required to respond to what the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan told a reporter was his greatest fear: “Events, dear boy, events.”

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.