Hidden Homelessness

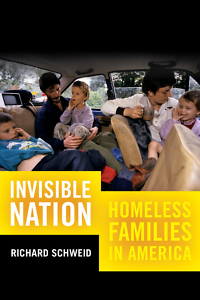

Richard Schweid considers the plight of homeless families in Invisible Nation

Ask comfortable Americans to describe their image of homelessness, and few of them will immediately mention families with children. We all know there are homeless kids in this country, but most of us don’t see or think about them much. Richard Schweid didn’t until 2002, when he happened to stay at a Dearborn, Michigan, motel where homeless families were being temporarily housed at government expense. Disturbed by the sight of children with “nowhere else to play but long, narrow hallways on dirty, threadbare carpeting,” he began to investigate the issue. Invisible Nation: Homeless Families in America, Schweid’s ninth book, offers a troubling look at the problem and attempted solutions in five U.S. cities, as well as a brief history of American responses to poverty from the Puritans onward.

Schweid, a Nashville native whose lively nonfiction books include Catfish and the Delta and Hereafter: Searching for Immortality, begins Invisible Nation in his hometown. Nashville’s new identity as a hot, hip “it” city has done little, he finds, to help her poorest citizens. During a stay in a grimy motel on Dickerson Pike, a rundown strip where prostitution and the drug trade flourish, Schweid meets Jennifer, a single mother of four, who has managed to move her family into a broken-down trailer after months of living in a motel and, for a while, their car.

Schweid, a Nashville native whose lively nonfiction books include Catfish and the Delta and Hereafter: Searching for Immortality, begins Invisible Nation in his hometown. Nashville’s new identity as a hot, hip “it” city has done little, he finds, to help her poorest citizens. During a stay in a grimy motel on Dickerson Pike, a rundown strip where prostitution and the drug trade flourish, Schweid meets Jennifer, a single mother of four, who has managed to move her family into a broken-down trailer after months of living in a motel and, for a while, their car.

The elements of Jennifer’s story are typical of many Schweid will encounter all over the country—an abusive husband, no education or job skills, no family to provide a safety net, personal tragedy leading to depression and drug abuse, all of it culminating in destitution and despair. What comes through most powerfully in Jennifer’s account is her desire to protect her children. Recalling their time in the motel, she says, “They never got any sunlight in there. I kept the curtains drawn all the time. I didn’t want my kids seeing out, and I didn’t want nobody seeing in. It was horrible, horrible.”

The conditions in shelters and motels, Schweid argues, are not just unpleasant and occasionally frightening for families like Jennifer’s. They’re physically and psychologically unhealthy. He cites studies showing that homeless children are far more likely to suffer serious illness and developmental problems than comparably poor children who have stable housing. Homeless children are also more likely to witness or be victims of violence, and they are particularly vulnerable to long-term problems such as depression, substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In a model he repeats for Boston, Fairfax, Portland, and Trenton, Schweid looks at the history of Nashville’s attempts to aid homeless families, and he talks with professionals—schoolteachers, advocates, and city officials—who deal with the problem day-to-day. Though every locality has its particular challenges and methods of approach, what they all share is the reality of homelessness as a problem on the rise. Between 2007 and 2012, for example, Nashville’s official count of homeless students in its schools increased by more than 700. Even in extremely wealthy Fairfax County, Virginia, a nonprofit offering meals and other services to the homeless has reported a sharp increase in the number of people seeking help.

Everywhere, the core of the problem seems to be simply a lack of affordable housing. In the Boston chapter, Schweid cites a 2013 study that determined an annual income of $67,200 was needed to meet the day-to-day living expenses of a single parent with two young children, yet the annual income of someone working full time for Massachusetts’s $9 minimum wage would total $18,720. Schweid later notes that an individual spending the federally recommended 30 percent of income on housing would need to earn more than $18 per hour to afford a two-bedroom apartment in any American city. Clearly, it’s nonsense to think that any single parent is just a steady job away from delivering a family out of homelessness.

And yet the idea that society owes destitute families nothing but grudging temporary aid and an opportunity to work has an enduring political currency. Schweid traces this line of thought all the way back to the Puritans, who initially showed some generosity toward their own poor but became increasingly tight-fisted as their communities grew. They looked down on the “idle poor” and hired out the children of penniless families against their parents’ wishes. Shaming poor people has a long history in the US, says Schweid, from eighteenth-century New York and Pennsylvania, where people receiving public assistance had to wear badges on their clothing, to the twentieth-century “man in the house” rules, which were used by states to deny federal welfare benefits to any mother who cohabited with a man. The so-called welfare reform overseen by the Reagan and Clinton administrations, which was focused primarily on getting people off assistance, was just a new iteration of a very old notion.

Schweid makes a compelling argument that our current policies, still fostered by entrenched social judgments about the poor, place an unconscionable burden on vulnerable children. He frankly advocates direct housing subsidies for homeless families, a move that would be expensive in the short run but would yield critical long-term benefits for the recipients, as well as the larger society. The problem of homeless families is, as he sees it, not a political or economic issue; it’s a moral one. “Children in the United States,” he concludes, “should not have to grow up this way.”

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.