Hidden Treasure, a Haunted House, and an Unlikely Trio of Detectives

In this debut novel, a boy braves bullies and worse to try to save his family home

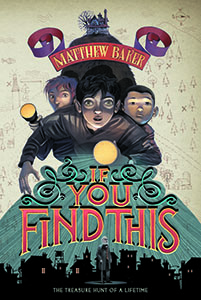

Part treasure hunt and part adventure tale but mostly the story of a boy who is both more courageous and more likeable than he thinks he is, If You Find This is Matthew Baker’s debut middle-grade novel. As an M.F.A. candidate in creative writing at Vanderbilt University, he did a semester-long independent study under my direction, during which he finished writing this novel and took the first steps in revising it. It has just appeared from Little, Brown.

The novel’s main character, Nicholas, is fascinated by music and numbers. He is also tormented by bullies. In an effort to find some heirlooms that his grandfather claims to have hidden in his old home (now the local haunted house), Nicholas develops an uneasy alliance with one of the bullies and with another picked-on boy. If they can find this treasure, Nicholas’s parents won’t have to sell their home, where Nicholas’s stillborn baby brother is buried under a pine tree. Nicholas talks to his brother through tunes he plays on his violin, and his brother answers by means of the wind through his branches.

Prior to his return to Nashville to give a reading at Parnassus Books, Baker recently answered questions via email:

Prior to his return to Nashville to give a reading at Parnassus Books, Baker recently answered questions via email:

Chapter 16: If You Find This has a unique narrative voice and an unusual plot and characters. What’s your standard answer when someone asks what your book is about?

Baker: If You Find This is the story of a boy named Nicholas Funes, whose mother has always told him that his grandfather is dead, until one day his grandfather turns up in town searching for their “lost family heirlooms.” (That’s the plot answer.) It’s about family secrets, social misfits, new friendships, and trying to save someone you love. (That’s the theme answer.) Nicholas is a music whiz and a math prodigy—he uses those other languages to try to understand the things he experiences—and so he narrates the book with a fusion of English, music notations, and math symbols. (That’s the fun answer.)

Chapter 16: I love the cover of If You Find This, and I think Nicholas bears a strong resemblance to you. Do you share any other characteristics with him?

Baker: You’re not the first person to say that! The cover was done by this brilliant artist named Iacopo Bruno, who as far as I know has never seen a picture of me. But Nicholas did turn out looking weirdly similar. Anyway, yes, Nicholas and I are alike in a number of other ways. We both grew up near the coast of Lake Michigan. We both were musicians as children. (I played piano/cornet, he plays piano/violin.) We were both obsessed with math (he’s better with primes than I ever was). We’re both pretty shy and pretty awkward socially. We’re both terrible swimmers.

Chapter 16: In the process of getting published, was there anything about the editorial process that surprised you?

Baker: I was shocked that the copyeditors wouldn’t let me use an uncapitalized “Dumpster.” Who’s out there to enforce the trademark? Dempster Brothers aren’t even in business anymore! Anyway, that’s why there are so many “garbage bins” in the book.

Chapter 16: Did your M.F.A. studies help in the writing process?

Baker: So much! The novel employs both first-person and third-person narration, makes some tricky maneuvers between past and present tense, juggles half a dozen subplots, and involves a huge cast of characters—I never could have managed anything on that level without the training I got while earning my M.F.A. (Honestly, before Vanderbilt, I had never even thought about things like “structure.”) (Or “revision.”)

Chapter 16: What did your professors and fellow students think about your writing a middle-grade book rather than something more “serious”?

Chapter 16: What did your professors and fellow students think about your writing a middle-grade book rather than something more “serious”?

Baker: I was up-front about my plan from the beginning. When I applied to Vanderbilt, my statement of intent said that I was going to write children’s literature. I mentioned that I was going to write books for adults too, but I emphasized that I wanted to write books for children. And Vanderbilt accepted me—not just into the program but for who I was.

Vanderbilt is special in that way. The English Department there is remarkably open-minded. When we wanted to start Nashville Review, for instance, we had to meet with the department chair to get our proposal for the magazine approved. And in the meeting I explained, “We’ll publish prose and poetry, but we also want to publish music and comics and movies and dances because all of that stuff is literature too.” The chair briefly deliberated and then gave us the go-ahead. I don’t think he necessarily agreed with our definition of literature, but that didn’t stop him from letting us try something different. I was lucky to end up at a program like that.

But it’s true that not everywhere in the literary world is free of prejudice. Take the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, which The New Yorker has called “the oldest and most prestigious writers’ conference in the country.” When you apply to Bread Loaf, the guidelines for your writing sample say, “Please do not send children’s or young adult literature.” In other words, children’s and young-adult writers are not welcome there. I’ve been to Bread Loaf but as someone who writes stories for adults. And honestly the conference was incredible—I learned so much, and became friends with so many talented writers, and got to sneak extra desserts at every dinner; I’m really grateful to have been given the chance to go. Still, I have to admit, there was something deeply uncomfortable about being somewhere where only half of me was welcome.

And that prejudice seems to happen both ways. I remember when Maile Meloy published her first middle-grade novel, The Apothecary, I read a review somewhere online that said something like, “Ugh, this book makes all of the typical mistakes that people who write books for adults make when they try to write for children—stick to adults, Meloy.” Reading that was pretty discouraging. I realized that there truly was a sense of “turf,” and that there were people on both sides who were bitterly determined to protect their “territory.”

I belong to both communities. I still don’t know how people are going to react to that. It’s kind of scary. Will they accept me for what I am, or will they cast me out as an abomination?

Chapter 16: More than one critic has said that children’s books often use avant-garde literary techniques, and your book has some unusual formatting that shows the reader certain aspects of Nicholas’s personality. For example, most sounds and speech are accompanied by a kind of stage-direction as to how loud they are, and you frequently use the mathematical symbols for “more than,” “less than,” “equal to,” etc., instead of words. Reviewers seem positive about these breaks from traditional formatting, but were you ever worried that readers would find them gimmicky or intrusive?

Chapter 16: More than one critic has said that children’s books often use avant-garde literary techniques, and your book has some unusual formatting that shows the reader certain aspects of Nicholas’s personality. For example, most sounds and speech are accompanied by a kind of stage-direction as to how loud they are, and you frequently use the mathematical symbols for “more than,” “less than,” “equal to,” etc., instead of words. Reviewers seem positive about these breaks from traditional formatting, but were you ever worried that readers would find them gimmicky or intrusive?

Baker: I wasn’t, but just about everyone else seemed to be. I had to fight—and fight, and fight, and fight—to find someone who would dare to publish a novel written in that hybrid tongue. Even Little, Brown was wary of taking the risk (and this is the company that published Infinite Jest!).

People used to spit on Tony Hawk at skateboarding tournaments. His rival when he was younger was this skater named Christian Hosoi, who was known for being very graceful, having a beautiful style. Tony invented lots of tricks, but compared to Christian, Tony skated like a robot. And there’s an interview in the documentary Bones Brigade where he talks about the rivalry. Christian’s fans used to ridicule him and say, “You don’t have style—you just have tricks.” And it was true. But in the interview Tony kind of shrugs and laughs, “That’s all I wanted. I just wanted new tricks.”

That’s how I feel about writing. I just want to invent new tricks to try. I’m glad that the reviews have been positive so far, but even if people started spitting on me from the sidelines, that would never stop me. Trying new tricks is what makes writing fun for me.

Chapter 16: I found the conversations between Nicholas and his dead baby brother the most haunting and moving parts of the book. How difficult were they to write?

Baker: I really struggled with those scenes. Aside from the personality overlaps between me and Nicholas, that’s really the only autobiographical element in the book—my mother lost a baby when I was a child, and afterward we planted a tree. I never talked to our tree, but that’s what was so difficult about writing those scenes: I finally had to let the tree speak and to listen to what that lost child had to say.

Chapter 16: I was particularly struck by this passage: “[Violins and fiddles are] actually the same instrument. The difference is how you play it. If you play the instrument this way, it’s a violin. If you play the instrument that way, it’s a fiddle. That’s the choice you have to make, as a musician, every time you play it. But you have to make the choice with yourself, too. You play yourself this way, you’re a fiddle. But you play yourself that way, and then you’re a violin, a completely different sound, something you never knew you could be.” Nicholas is keenly interested in how our past influences us, how people change, what makes us who we are. Were these issues that occupied your mind at that age as well?

Baker: Yes, probably too much so. Here’s a prime example: I took both piano lessons and cornet lessons in middle school. And around the same time my teachers both said something very similar to my mom. The basic gist was, “If he keeps doing this, he could do it professionally.” I’m sure my teachers probably meant that to be encouraging, but instead it really troubled me. I thought, “If I keep doing this, then that’s going to be my career, and I’m going to be a musician forever.” I liked playing music, but I wasn’t sure I always would, and plus what if later on I found something that I liked better? I was worried my future self would get stuck doing something he didn’t love because my past self had made the wrong decision. I wasn’t ready to commit to anything yet. I couldn’t handle that kind of responsibility. I quit piano, I quit cornet, and I spent the next few years building forts in the woods.

Baker: Yes, probably too much so. Here’s a prime example: I took both piano lessons and cornet lessons in middle school. And around the same time my teachers both said something very similar to my mom. The basic gist was, “If he keeps doing this, he could do it professionally.” I’m sure my teachers probably meant that to be encouraging, but instead it really troubled me. I thought, “If I keep doing this, then that’s going to be my career, and I’m going to be a musician forever.” I liked playing music, but I wasn’t sure I always would, and plus what if later on I found something that I liked better? I was worried my future self would get stuck doing something he didn’t love because my past self had made the wrong decision. I wasn’t ready to commit to anything yet. I couldn’t handle that kind of responsibility. I quit piano, I quit cornet, and I spent the next few years building forts in the woods.

Chapter 16: What did you like to read when you were Nicholas’s age?

Baker: Everything. I loved middle-grade books like My Side of the Mountain and Island of the Blue Dolphins; I devoured young-adult series like Animorphs and His Dark Materials. I read adult fiction like Tolkien and Crichton and Frank Herbert. I read Moby-Dick for the first time around that age too. (Some parts were boring to me, but then again, some parts of that book are boring to me even today.) And at the same time, I still liked children’s books like Winnie-the-Pooh. I didn’t pay much attention to age categories, honestly. I read whatever interested me.

By the way, isn’t it kind of weird that children’s publishing has so many subcategories while adults just get lumped all together? Shouldn’t adult publishing have subcategories too? You know, like “geriatric novels” or something?

Chapter 16: Do you still read middle-grade and/or young-adult books for pleasure?

Baker: Definitely. Here are the last five books I read: Ambassador by William Alexander (middle-grade), This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (young-adult), Orlando by Virginia Woolf (adult/geriatric), Vivian Apple at the End of the World by Katie Coyle (young-adult), and Building Stories by Chris Ware (adult/geriatric). So my tastes really haven’t changed—I still like reading about all ages.

Chapter 16: What are you working on now?

Baker: Revising another middle-grade novel for Little, Brown, finishing a short-story collection that I can’t figure out what to title, and trying and failing to find someone at Marvel who will pay me to write comics.

Tracy Barrett is a writer who lives in Nashville. Her tenth novel, a young-adult retelling of Cinderella entitled The Stepsister’s Tale, was published in 2014 by Harlequin TEEN.