Hiking Through History

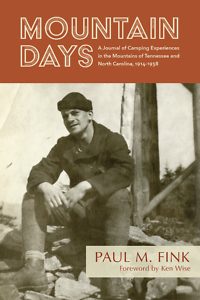

Paul Fink describes early forays into the Smoky Mountains in Mountain Days, a lost classic of wilderness travel

Paul M. Fink (1892-1980) lived his entire life in Jonesborough, Tennessee, within easy striking distance of the Smoky Mountains, which he came to know intimately through decades of backpacking. As a young man he became a leader in the movements to create both the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Appalachian Trail. Mountain Days: A Journal of Camping Experiences in the Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina, 1914-1938 collects Fink’s accounts of 20 trips into the mountains over a 24-year period, along with seven essays offering hiking advice and 106 of his photographs taken during early forays into the future park.

In 1960 Fink collected and edited his early journals, but they were not published until 1975, and then in a very limited printing with the title Backpacking Was the Only Way: A Chronicle of Camping Experiences in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Editor Ken Wise chose to issue the new print edition, published by Western Carolina University, under Fink’s original title. (The Hunter Library at Western Carolina University also offers an open digital version.)

In 1960 Fink collected and edited his early journals, but they were not published until 1975, and then in a very limited printing with the title Backpacking Was the Only Way: A Chronicle of Camping Experiences in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Editor Ken Wise chose to issue the new print edition, published by Western Carolina University, under Fink’s original title. (The Hunter Library at Western Carolina University also offers an open digital version.)

Mountain Days offers precisely what its subtitle proclaims: a series of well-written journals about camping in the Smoky Mountains. On the first trip, in August 1914, 22-year-old Fink and three friends were ill prepared for a six-day walk from Jonesborough to the top of Bald Mountain and back. “Our cook kit was rudimentary, and we started with most of our food in paper bags carried in our hands,” he writes. “What a fix we would have been in if a sudden shower had caught us!”

After the first 15 miles, the group’s street shoes soon make tenderfoots of them all, and Fink describes creative efforts to bandage daily blisters. Nevertheless, they reach their intended destination and soon begin setting their sights on loftier peaks. Walter S. Diehl, the friend who enticed Fink and the others to hike into the wilderness, becomes a recurrent character in many of the later trips.

Even in the 1910s and ’20s, most of the places Fink and his friends rambled could not be called untraced wilderness. The apex of their first hike was a much-used summer pasture, cleared of trees by early lumber operations and crisscrossed by farm trails and abandoned wagon roads. On one rainy trip, his group loses their way en route to the swamp-like Miry Ridge, becoming “completely lost in a tangle of laurel, while the bushes completed the job of drenching started by the rain.” But it is local traffic that eventually puts Fink back on track: “Retracing our steps with difficulty, we found that we had left the road one ravine too soon. The real trail was plainly marked and not to be mistaken — there were too many signs of use.”

Fink often describes colorful locals who live amid the mountain fastness. During his trips in the 1920s, many of these encounters involve tales of moonshine. The brother of a town marshal in Townsend, Tennessee, describes Quill Rose, a “famous moonshiner” on Hazel Creek: “Quill made and drunk more licker than ary other man that ever lived in these mountains. When he got too old an’ broke-down to make his own licker, he hired himself two men to keep him supplied.”

While Fink and his friends were true pioneers in recreational backpacking, only in their later, more ambitious trips did they finally become pathfinders. On Fink’s 29th birthday — June 8, 1921 — amid a mission to measure the correct height of Mt. Le Conte using scientifically calibrated barometers, he and his companions climbed their way into a pristine wilderness:

Here, in the triangle encompassed by Mts. Le Conte, Collins and Mingus, is the wildest, ruggedest country I’d ever seen. There are no valleys, only ravines and canyons, the ridges between knives and saws, with scores of rocky cliffs. Over it all grows a primeval forest of spruce and balsam on the heights and mingled hardwoods on the lower levels, untouched by axe or saw.

Wise, the editor behind this enjoyable reissue, is a research librarian and professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville who has turned the rescue of historic Smoky Mountain manuscripts into something of a cottage industry. He was the coeditor of both Mount Le Conte and the delightful Smoky Jack, two “lost” works of early mountain authority Paul Adams. Wise is also author of several of his own books on Appalachian hiking and history. In his well-researched preface to Mountain Days, he explains Fink’s importance to both the national park and famous trail that would follow in Fink’s footsteps.

In 1938, 24 years after the first trip and four years after the official charter of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Fink returns to Roan Mountain with his old friend Walter Diehl. “Now we were growing older, fatter and lazier, and inclined to take our outings a little less vigorously,” Fink confesses. His hiking companion says, “It makes no difference to me how rough the country or how heavy the pack, just so I don’t have to get more than a hundred yards from the car.” Still they rouse themselves sufficiently to hike from Carvers Gap to the Hump, a place they had never been:

The whole mountain was ours. Not another person was in sight, not even the livestock usually grazing on the lush grass of the high meadows. As we sat eating our lunch in the lee of a rocky outcrop, a pair of questing ravens winged over, almost at arm’s length. They were even more startled than we, emitting loud squawks and flapping up top speed as they put distance between us.

Mountain Days bristles with such natural moments, removing the distance between modern readers and those hikers lucky enough to have experienced the Smokies in the days before park or trail.

Michael Ray Taylor chairs the communication and theatre arts department at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is working on a book about Tennessee caves and cavers.