Honoring the Struggle

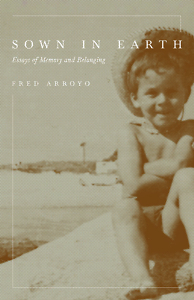

Fred Arroyo’s Sown in Earth offers a tender understanding of the immigrant experience

“We had no books in our house on Reed Avenue,” writes Fred Arroyo in Sown in Earth: Essays of Memory and Belonging. Nevertheless, the recollections of childhood in these moving essays have all the sensory detail of someone for whom memory is guided by language.

Most of the essays center on the relationship between Arroyo, now an assistant professor of English at Middle Tennessee State University, and his father, originally from Puerto Rico, who met his mother while working in a Green Giant cannery in Michigan. Arroyo depicts a distant father who struggled with alcoholism and was sometimes violent, but who ultimately represents the struggle of every immigrant longing to find his place in a world where he doesn’t belong.

Most of the essays center on the relationship between Arroyo, now an assistant professor of English at Middle Tennessee State University, and his father, originally from Puerto Rico, who met his mother while working in a Green Giant cannery in Michigan. Arroyo depicts a distant father who struggled with alcoholism and was sometimes violent, but who ultimately represents the struggle of every immigrant longing to find his place in a world where he doesn’t belong.

“They’d sit on the front porch or out in the backyard at the picnic table, and they’d talk over steaming bowls and full glasses,” recalls Arroyo, of his father and his friends, “and on the edge of their animated voices I began to hear the importance of memory and story, and no matter how far you were from home, you could gather in the company of other men and bridge the endless lonely distances you carried inside.”

Arroyo writes eloquently about the instability of his childhood shuttling back and forth from Connecticut to Michigan, where his mother’s family lived, while being at the mercy of his father’s unsteady jobs and mercurial temper. But in these memories Arroyo finds a way of understanding his past and the indelible ways in which it has shaped him as a writer. “I had seen my father drunk before,” he writes, “witnessed him with the eyes of distance and closeness, the eyes of a camera saving what would last forever, and I felt the silence between us grow inside me, felt its weight pushing against my chest, and wondered if this is how the roaring of words begins.”

The title essay, which could be considered the emotional anchor of the book, is a meditation on the summer that Arroyo, 14 years old at the time, worked alongside his father and his father’s friends in the potato fields of southwestern Michigan. In these pages Arroyo warmly recounts feelings of kinship with the men, moments of shared experience that allow him a tender understanding of their struggle. “Their bodies were like old books forgotten on a dusty shelf and in the pages their muscle and sweat were the verbs and conjunctions that composed the truth of their lives,” he writes. The realization that he is also one of them, if not the same, gives him a purpose for his life’s work. “Those days of dew, sun, corn and potatoes will always be a part of me. They are a part of the bloodline I’ll work to continue until I die, and then maybe they’ll fall apart like crumbled dirt and turn to dust and become part of the sun and the sky and the earth. They grow in every new word I write. … They grow in each new word that’s sown in earth.”

The title essay, which could be considered the emotional anchor of the book, is a meditation on the summer that Arroyo, 14 years old at the time, worked alongside his father and his father’s friends in the potato fields of southwestern Michigan. In these pages Arroyo warmly recounts feelings of kinship with the men, moments of shared experience that allow him a tender understanding of their struggle. “Their bodies were like old books forgotten on a dusty shelf and in the pages their muscle and sweat were the verbs and conjunctions that composed the truth of their lives,” he writes. The realization that he is also one of them, if not the same, gives him a purpose for his life’s work. “Those days of dew, sun, corn and potatoes will always be a part of me. They are a part of the bloodline I’ll work to continue until I die, and then maybe they’ll fall apart like crumbled dirt and turn to dust and become part of the sun and the sky and the earth. They grow in every new word I write. … They grow in each new word that’s sown in earth.”

In trying to convey the cruelty and complexity of his father in the only way he knows how — through writing — Arroyo acts as a witness for all of the men whose names he doesn’t remember. In these essays, he accomplishes what he sets out to do: “to work in a way that honors the struggle and dignity of their lives.” And in doing so, he sets in motion the linguistic memories that compose a life, however incomplete. “The more I delve into the memories of my father, the more I realize his life is an unfinished book; it continues to grow the more I try to write it, new pages revealing themselves day after day, as if this growing will go on without end. Even if I take the next twenty years to write it, I won’t make his life and story any more complete. The story will still be fragmented, small, minor, adrift in a turbulent sea between a kitchen and an island, between a father and son.”

Although his father’s life refuses summation in the end, Arroyo manages to reach an understanding of himself and the forces that shaped him to become the writer he is today.

Joy Ramirez holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature. She taught Italian at Vanderbilt University and Colorado College. She now writes and lives in East Nashville.