Hopeless Dreamers

Jack Hitt goes in search of the defining American trait, and finds himself amid a bunch of adorable amateurs

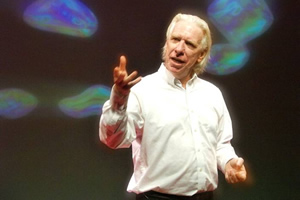

There’s something heady about watching a pro wrangle with the definition of American identity—the massaging of that old thing. That’s not least because the act is a little meta: the impulse to define and redefine, ad infinitum, who we are as Americans is itself quintessentially American. Almost as much as we love to reinvent ourselves, we love to reinvent the definition of ourselves, to give that narrative a fresh coat of paint. In Bunch of Amateurs: A Search for the American Character, Jack Hitt puts himself to this uber-American task, and his presence on the job should alone pique interest in the results. Few other contemporary nonfiction writers working today are as prepared to hunt down and dissect intrinsically American specimens—and to engage a popular audience with the findings—as this guy.

A contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and contributor to Rolling Stone, Wired, and Harper’s (most recently a widely shared blog post about the Republican national convention), Hitt is perhaps best known as a longtime contributor to the public-radio show This American Life. For nearly two decades he has reported all sorts of American-character stories, zany and serious alike: from a legendary former neighbor of his, rumored to have had one of the earliest known sex changes, to a hilariously botched community theater production of Peter Pan, to the Democratic party in crisis, to dinosaur buffs and mobsters and prisoners performing Hamlet, to, most recently, devout Christians who count cards in casinos. His work for TAL has been both funny and grounded in assiduous investigative reporting, two characteristics that are on fine display in Bunch of Amateurs.

In the book’s introduction, Hitt presents an enthusiastic case for the idea that amateurism is central to American identity. The word amateur typically suggests a novice, a dilettante, a dabbler. But Hitt argues for a broader view. To him, American amateurs are “hopeless dreamers, made practically adorable by their obsessive love for some one true thing, and each and every one of them charged with the potential of being a genius and making a crucial discovery…[t]he lovable Poindexter who just might possibly stumble upon the next big thing.” They are, he goes on, “either outsiders mustering at some fortress of expertise hoping to scale the walls, or pioneers improvising in a frontier where no professionals exist, … forever rebelling against the king or lighting out for the territories.”

In the book’s introduction, Hitt presents an enthusiastic case for the idea that amateurism is central to American identity. The word amateur typically suggests a novice, a dilettante, a dabbler. But Hitt argues for a broader view. To him, American amateurs are “hopeless dreamers, made practically adorable by their obsessive love for some one true thing, and each and every one of them charged with the potential of being a genius and making a crucial discovery…[t]he lovable Poindexter who just might possibly stumble upon the next big thing.” They are, he goes on, “either outsiders mustering at some fortress of expertise hoping to scale the walls, or pioneers improvising in a frontier where no professionals exist, … forever rebelling against the king or lighting out for the territories.”

Hitt sees these types at work everywhere in American culture, in the annals of history and in modern times, from bloggers to storm spotters, from computer hackers to people messing around with technology that allows them to see through materials (yes, basically Xray Specs tinkerers), and even in The Wizard of Oz, “an American narrative about self-invented outsiders overwhelming the domain of professionals.” Then there’s Ben Franklin, with whom Hitt opens his exploration. Hitt is a big Franklin buff, which goes some way toward explaining why that quintessential dabbler gets first—and last—act in the book.) He presents Franklin as a founding “New World amateur,” fundamentally pitted against John Adams, “a man of protocol and schedules, … the kid who always did his homework on time.” For Hitt, the two men constitute “twin poles of the American psyche.” Hitt’s sheer delight in the narrative of Adams and Franklin as reluctant teammates on business in Paris in 1778 shines through his prose, crisp and charmingly vernacular throughout the book: “Franklin thought Adams was an officious prick. Adams thought Franklin was a decadent blowhard,” he writes. “Their relationship is key to the creation of the mythic American tinkerer of the Old World’s imagination.”

Hitt pictures Adams trying to look fully the Louis XVI part, “standing at the gates of Versailles…in his official wig, his rent-a-sword, his fresh breeches.” Donning coonskin cap and rustic coat, Franklin was, by contrast, “our meta-pioneer,” Hitt writes. “He created this image of us as clean-living bumpkins but also as the pioneering amateurs we often are, fiddling our way into becoming something new by pretending to be something we’re not.”

In succeeding chapters, Hitt dives deep—way deep—into the worlds of specific amateur pursuit. He tells of birdwatchers and bloggers taking down Ivory Tower ornithologists who claim to have spotted the ivory-billed woodpecker (the “WMD of ornithology,” one source describes it). He hangs out with “homebrew geneticists” who attempt to extract DNA using Tupperware containers, cut-up subway cards, and glycerol suppositories. He visits backyard astronomers and paleontologists, fields that are “teeming with amateur passion right now and always have been,” he writes: “It’s probably not a coincidence that both fields take us into the biggest questions. If you’re going to fiddle around on the weekends, why not solve the secret of the universe or the mystery of life?” In each, Hitt finds passionate individuals trying to disprove a traditional theory or belief pattern, or simply trying to make something their own damn selves out of string and spit.

In succeeding chapters, Hitt dives deep—way deep—into the worlds of specific amateur pursuit. He tells of birdwatchers and bloggers taking down Ivory Tower ornithologists who claim to have spotted the ivory-billed woodpecker (the “WMD of ornithology,” one source describes it). He hangs out with “homebrew geneticists” who attempt to extract DNA using Tupperware containers, cut-up subway cards, and glycerol suppositories. He visits backyard astronomers and paleontologists, fields that are “teeming with amateur passion right now and always have been,” he writes: “It’s probably not a coincidence that both fields take us into the biggest questions. If you’re going to fiddle around on the weekends, why not solve the secret of the universe or the mystery of life?” In each, Hitt finds passionate individuals trying to disprove a traditional theory or belief pattern, or simply trying to make something their own damn selves out of string and spit.

And his stories are most lively when one individual stands out, such as Meredith Patterson, a tattooed, “off-the-grid” scientist in San Francisco whose quest is to inject glow-in-the-dark plasmid—fish genes—into yogurt: voila, “Glogurt,” or glow-sticks you can eat, a creation that ravers everywhere don’t yet know they need. Patterson is an irresistible character, and her dependence on cheap materials and ingenious hacks is fascinating. Disposable insulin needles for pipettes, a $5 floppy drive motor for a centrifuge, a pressure cooker, Astroglide: this is the stuff of her lab. Hitt chronicles the joy she takes in having built her equipment from scratch, and the way she’s insulated from the stymieing effects of failure in a way that salaried workers, for example, might not be. “At an office, failure is profoundly frustrating since it’s known to others and embarrassing,” he writes. “But if the entire rig on your kitchen table is your own creation, … failure is just a glitch in the system you’ve built.”

Here and elsewhere in the book, Hitt dips into what almost comes off as motivational patter: “It turns out that ignorance is bliss and, in many cases, a more productive perch to start from. Not knowing anything about something is often precisely what’s needed to see something new.” In the end, though, the stories and the characters are the thing. Rare may be the readers who are so omnivorous in their interests that they’ll consume each and every chapter of Bunch of Amateurs with equal avidity, but Hitt’s lively and ultimately convincing argument about amateurism as a mainstay of American identity makes a lasting, and charming, impression.

Jack Hitt will discuss Bunch of Amateurs: A Search for the American Character at the twenty-fourth annual Southern Festival of Books, held October 12-14 at Legislative Plaza in Nashville. All events are free and open to the public.