How Now Shall We Live?

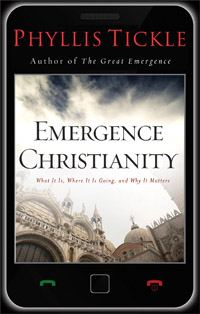

Phyllis Tickle examines the Christian Emergence movement in the twenty-first century

A former teacher, college administrator, and publisher who has written more than two dozen books—many of which describe her own faith journey and practices as an Episcopalian—Phyllis Tickle is also the founding editor of the religion department at Publisher’s Weekly. This position afforded her a unique view of the trends sweeping through late-twentieth-century Christianity. As she writes in The Great Emergence (Baker Books, 2008), “I became a student of religion by being cast dead center of the maelstrom and having to learn to swim right there and right then.” After Tickle left Publisher’s Weekly, she began to gather information from sources throughout the Christian community in North America and elsewhere and put together her own impressions of the movement dubbed “The Great Emergence.”

Tickle is by no means alone in her belief that Christianity—and specifically Protestantism in North America—is undergoing a cataclysmic shift. Buffeted by science, technology, politics, economics, and culture, the “faith of our fathers” appears to be facing obstacles undreamed of by previous generations. But according to Tickle and many other scholars, this has all happened before—several times. Who can forget the events of five hundred years ago when Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the Wittenberg church door and ushered in the violent upheaval that gave birth to Protestantism? Go back another five centuries, more or less, and you find the Great Schism, which resulted in the separation between the Roman and Orthodox churches and changed the landscape of Christianity forever.

Tickle is by no means alone in her belief that Christianity—and specifically Protestantism in North America—is undergoing a cataclysmic shift. Buffeted by science, technology, politics, economics, and culture, the “faith of our fathers” appears to be facing obstacles undreamed of by previous generations. But according to Tickle and many other scholars, this has all happened before—several times. Who can forget the events of five hundred years ago when Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the Wittenberg church door and ushered in the violent upheaval that gave birth to Protestantism? Go back another five centuries, more or less, and you find the Great Schism, which resulted in the separation between the Roman and Orthodox churches and changed the landscape of Christianity forever.

Such transformational periods, or “hinge times,” result when internal and external forces produce the shattering of traditional systems of religious expression, with a threefold result: the development of brand-new modes of belief, the eventual restructuring of existing institutions, and finally a dramatic increase in the dissemination of the faith. As Tickle explained in The Great Emergence, which has just been released in paperback, “When an overly institutionalized form of Christianity is, or ever has been, battered into pieces and opened to the air of the world around it, that faith-form has both itself spread and also enabled the spread of the young upstart that afflicted it.” This pattern had already been described by historians, but Tickle examined in the light of history the incredibly swift and often overwhelming changes of our own era and made predictions for a lay audience about where Christianity’s growing pains might take it next.

In her new book, Emergence Christianity, Tickle takes up the subject once again, while narrowing her focus to consider in detail many of the new pathways the Great Emergence has produced in the Christian community so far. She begins with influential global events of the twentieth century, such as the Catholic Worker movement, the birth of Pentecostalism, and the founding of the ecumenical Christian communities of Iona in Scotland and Taizé in France. Next she examines how these unique visions led to the establishment of small house churches and pub theology groups, among others. These organic, loosely structured organizations—which may or may not retain ties to an established denomination or “inherited church”—tend to be ecumenical, communal, and self-correcting, with an emphasis on equality, diversity, peace and justice, hospitality, and an “ancient-future” aesthetic that often combines liturgy and a reverence for the Bible with a heavy dose of technology. The author charts the development of these de-centralized and de-institutionalized faith communities as “a people to be, not a place to go to.” Phyllis Tickle recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: In Emergence Christianity, you write, “This is now the fourth time I have spoken in book form about what is happening to us as North American Christians in the twenty-first century.” Why has this subject captured your attention so completely and for so long?

Chapter 16: In Emergence Christianity, you write, “This is now the fourth time I have spoken in book form about what is happening to us as North American Christians in the twenty-first century.” Why has this subject captured your attention so completely and for so long?

Tickle: I spent the bulk of my earlier working life in the book-publishing industry. When, at age fifty-nine, I decided to retire from all of that, I was, so to speak, less than successful at doing so. My intention had been to devote myself to writing, but within thirteen months of my non-retirement retirement, I received a call from Publishers Weekly, the trade journal of the book industry. The call was pretty direct and to the point.

It was 1992, and religion books were suddenly selling like crazy, becoming not only the country’s bestsellers, but also its best-margins money-makers. Because the bulk of religion publishing had previously been done by denominational houses, Publishers Weekly had never had a religion department, much less any need for one. So the call was a simple question: would I come out of retirement for eighteen months, set up a department, and get it in running order before returning to my intended writing? Well over a decade later, of course, I was still at Publishers Weekly, but the question had changed.

Within months of my going to Publishers Weekly, it became screamingly apparent that the issue was not establishing a department—though we certainly did that—but rather, the question was one of trying to make sense of what was happening, why it was happening, where it was going, how one could responsibly and profitably publish into it. In order to address those issues, I had to do what every old academic always does: I went to the scholarship and there found literally reams of commentary, historical analysis, informed conversation, etc., about exactly what was indeed happening and why. In a manner of speaking, in other words, I became a student of Emergence by default and for what originally were purely commercial reasons.

Chapter 16: You argue in The Great Emergence that Christians in North America are participating in a “conversation” that crosses denominational lines and that will ultimately “rewrite Christian theology into something far more Jewish, more paradoxical, more narrative, and more mystical.” Five years later, do you still believe Emergence Christianity is on the same path?

Tickle: There is no question but that Emergence Christianity is indeed on that path. There is, however, one difference of significance now over my earlier words: that is, what could legitimately be called a “conversation” a decade ago has now become a movement—a full-blown and maturing movement.

Chapter 16: “Religion, whether we like it or not, is intimately tied to the culture in which it exists,” you write in Emergence Christianity, and your most recent books focus on the ways that culture and other factors are changing our religious practices. What about the influence that Christianity brings to bear on the culture surrounding it—is that relationship, too, being redefined?

Tickle: Absolutely. And we need to note just here that the relationship between any religion and the society or culture hosting it is always a two-way exchange. It is the business of religion to answer for its hosts the question of where ultimate authority and meaning rest. It answers, in a sense, the “How now shall we live?” question. At the same time, the hosting society orders or ranks the issues that need addressing and resolution. To some extent—and arguably with the exception of mystics and prophets and seers—the culture also furnishes the lens through which theology and ecclesiology can be seen or comprehended or amended. Each limits the other, that is, but to the benefit of the whole they create, at least sociologically speaking.

Tickle: Absolutely. And we need to note just here that the relationship between any religion and the society or culture hosting it is always a two-way exchange. It is the business of religion to answer for its hosts the question of where ultimate authority and meaning rest. It answers, in a sense, the “How now shall we live?” question. At the same time, the hosting society orders or ranks the issues that need addressing and resolution. To some extent—and arguably with the exception of mystics and prophets and seers—the culture also furnishes the lens through which theology and ecclesiology can be seen or comprehended or amended. Each limits the other, that is, but to the benefit of the whole they create, at least sociologically speaking.

Chapter 16: You have written that “the injunction against homosexuality in all its forms is the last of the biblically based injunctions still standing” in the historical church. In The Great Emergence, you go so far as to categorize Christianity’s turmoil over this issue as “a battle to the death.” What do you see as the spiritual and cultural consequences of such a fight?

Tickle: Well, first let’s clarify or nuance that partial quote which is a bit truncated here: that is, the gay issue is indeed the last puck or playing piece in a very serious game or fight or jousting match—whatever figure one wishes to use—but it is the last piece in one particular area of a large playing field. The Great Reformation established sola scriptura, scriptura sola—only Scripture and Scripture only—as the base of authority for Latinized culture, and that authority more or less held from the Great Reformation right up until about a hundred and sixty or seventy years ago and the advent of the so-called peri-Emergence.

During those decades leading to the de-establishment of sola scriptura and the coming of Emergence itself, the battle of authority and where it rests, has, sociologically speaking, moved along a spectrum from abolition to racial equality to gender equality to acceptance of divorce to acceptance of re-marriage and now to acceptance of gayness. Once that last conflict is resolved, there are no more pieces with which to play the sola game from the sociological point of view, though there are from, for instance, the political point of view.

The immediate consequences of the gay part of the conflict are, of course, very apparent just now in public (as well as in ecclesial and theological) furor. Angry division, fear, even violence attend just now because of the absolute foundational nature of what is being decided. Each time we have made a move farther up along this sociological spectrum—i.e., from abolition all the way now to gayness—there have been violent repercussions and analogous distress. The only real difference with the gay issue is that, because it is the last piece with which to play this part of the game or delineate this segment of the larger argument, it brings with it an added intensity—an intensity, if you will, almost of desperation.

Chapter 16: Many Emergence Christianity organizations eschew the centralized authority of the “inherited church,” including seminary-trained “experts.” In your view, has this stance been significantly influenced by the clergy sex-abuse scandals of recent years?

Tickle: There is no question that those scandals have affected every part of our society, be it Christian or not. The inevitable result is a scorning or scoffing attitude toward inherited or established Church and its ways. Beyond that predictable—almost inevitable—and general repugnance, however, I doubt that one could really make a case for the scandals’ having had any greater impact on Emergence Christians or Emergence Christian organizations than on any other part of the culture.

Chapter 16: As a church becomes less hierarchical and more self-organizing, without institutional permanence or an external source of oversight, is it in your view also more likely to stray so far outside traditional Christian doctrine as to become essentially non-Christian?

Tickle: Good heavens, no! Hierarchy is not the only way to organize living organisms, be they individuals or groups, flocks or even ant hills. It just happens to be the way to which we have grown accustomed, particularly over the semi-millennium since the Great Reformation and our adoption of Reformation-influenced social and political and economic ways of doing business.

Chapter 16: You point to the “dramatic and irresistible” forces molding contemporary American society and advise, “We can either be its passive medium or its active architects.” As an author, what would you wish your own legacy to be in this process?

Tickle: Only that what I have written and spoken prove to have been accurate, useful, and as devoid of Phyllis Tickle as any principles and insights and observations ever can be devoid of their human conduit.